Canaux

108470 éléments (108470 non lus) dans 10 canaux

Actualités

(48730 non lus)

Actualités

(48730 non lus)

Hoax

(65 non lus)

Hoax

(65 non lus)

Logiciels

(39066 non lus)

Logiciels

(39066 non lus)

Sécurité

(1668 non lus)

Sécurité

(1668 non lus)

Referencement

(18941 non lus)

Referencement

(18941 non lus)

éléments par Sameer Singh

BetaNews.Com

-

Underhyping Snapchat

Publié: février 7, 2017, 7:58pm CET par Sameer Singh

The media, analyst and investor communities clearly have a love-hate relationship with Snapchat. In the run-up to its IPO, it was hailed as the next great technology company (in part due to Snap's own communication efforts). And now that its S-1 is out, the commentary has turned quite negative. As always, the truth is somewhere in the middle and public filings paint a very clear picture of why that is. The chart at the top of this post shows quarterly revenue for Snap compared with that of Twitter and Facebook, aligned by founding year (sourced from their respective IPO prospectuses).… [Continue Reading] -

Pokémon Go and business model innovation

Publié: juillet 12, 2016, 6:07pm CEST par Sameer Singh

After months of hype, Pokémon Go finally began rolling out in a few countries this week. At this point, I can safely say, it has turned out to be one of the biggest viral hits in recent years. While the Pokémon IP played a significant role in the game's quick uptake, I believe that Pokémon Go's status as the first accessible augmented reality game at scale will be much more important to its long-term success. There are multiple elements of business model innovation at play here, far deeper than a simple extension of pre-existing IP. Many analysts have already put… [Continue Reading] -

Google vs Apple: Contrasting approaches to app store evolution

Publié: juin 21, 2016, 5:49pm CEST par Sameer Singh

This year, Google I/O and WWDC seemed to lack the excitement seen in years past with most announcements being fairly mundane -- a combination of maintenance/incremental updates and "me-too" products -- inevitable at this point in the maturity cycle. The most interesting part of these developer events was really the contrasting approaches Google and Apple have taken to evolve the app ecosystem. Unsurprisingly, both approaches are diametrically opposed to each other and favor each company's business model. However, the "winning standard" will necessarily be one that better serves the needs of both consumers and developers. The biggest news from Google… [Continue Reading] -

Chatbots, apps and the path to victory

Publié: avril 15, 2016, 12:38pm CEST par Sameer Singh

This week, Facebook opened up its long awaited bot platform within Messenger following similar moves from LINE, Telegram and Kik. It almost seems as though bots have peaked on the "Hype cycle" in just a few short weeks since they entered mainstream discussion. This isn't a criticism of the concept, but rather of industry discourse. Chatbots certainly have potential, but where that lies is just as important as the eventual scale. Facebook demonstrated quite a few bots during this week's F8 conference. Unfortunately, it appeared as though many of them were just apps built inside a messaging app (a concept… [Continue Reading] -

Explaining the struggles of Apple Pay and mobile payments

Publié: mars 14, 2016, 4:34pm CET par Sameer Singh

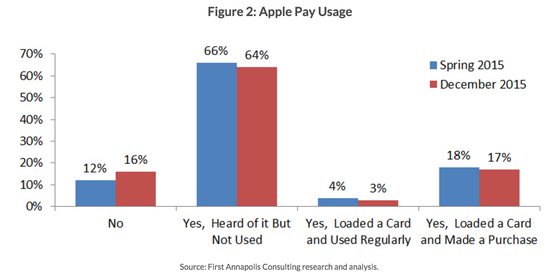

Apple Pay was introduced 18 months ago to rave reviews from the press and technology analysts. It was billed as an example of "mobile payments done right" -- simple, intuitive and painless. And yet, its impact has been muted at best, even in key western markets. According to a recent survey, 80 percent of iPhone 6 users had never used the service and just 3 percent used it regularly. Customer satisfaction among Apple Pay users remains high, but word-of-mouth appears to have had no impact on adoption. What is the cause of this divergence?

Looking at these figures, it appears that Apple Pay is struggling to "cross the chasm" between early adopters and mainstream consumers. Early adopters genuinely looking for a mobile payment solution would have no doubt been delighted by Apple Pay's implementation. However, most "normals" aren't specifically looking for a mobile payment solution. Any substitute to existing payment solutions has to be superior enough to existing offerings to break long established habits (in this case, pulling out a credit card). And it is here that Apple Pay, and mobile payment solutions in general, face a key challenge.

From the perspective of mainstream consumers, mobile payments are no more "mobile" than a credit card or cash. Security and privacy have never been a draw except for a vocal minority. The only benefit left is transaction processing time or "convenience". Last year, most early adopters (and some analysts) argued that mobile payments were so much more convenient than existing payment solutions that it was only a matter of time until adoption exploded. Except, it hasn't. And the longer you think about it, the more superficial this "convenience" argument seems.

If a "normal" iPhone user has to make a trip to the closest big box retailer, say Walmart, would Apple Pay improve his experience? Does saving ten seconds at the checkout counter matter when he has to wait ten minutes for his groceries to be scanned and bagged anyway? Even if the wait is a few minutes for other types of in-store purchases, the added convenience is minimal. At the very least, it isn't enough of an experience boost to change the deeply-ingrained habit of pulling out a credit card. Now, if the credit card itself could save a few seconds, it would be actively utilized. And that's a selling point for contactless payments, not for mobile payments.

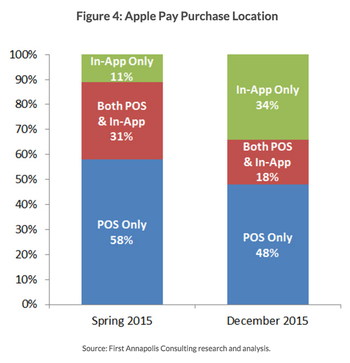

Now, this isn't to say that mobile payments are a completely failed experiment. The convenience argument does apply when the purchased product or service is delivered instantaneously. In other words, mobile payments are a much more elegant solution when used for digital purchases made on the smartphone itself (or order ahead solutions for in-store pickup). Here, mobile payments solutions add convenience by saving you the trouble of manually adding in your credit card or verification details. Unsurprisingly, this is exactly what the survey in question found among Apple Pay users.

While Apple Pay usage remains low, the share of in-app transactions tripled during the survey period even among the early adopter base of Apple Pay users. Efforts to push in-store mobile payments haven't paid off until now and I don't see any trigger that will change this in the near future. It may be time for platform owners to pivot and focus marketing efforts on in-app transactions instead.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

Self-driving cars: incrementalism vs. full autonomy

Publié: janvier 20, 2016, 1:46am CET par Sameer Singh

Last week, I came across an interesting piece by Jan Dawson about self-driving cars. In it, he argued that Tesla's (and possibly Apple's) approach of incremental improvements in automation was vastly superior to Google's goal of achieving full automation. His primary argument is that consumers need to purchase and experience semi-autonomous vehicles before they can trust the technology enough to purchase fully autonomous vehicles (especially given the likely cost of purchase). While this does appear to make some sense, there is a key flaw in this argument. The goals and business models of companies following these two approaches are dramatically different.

What do Tesla (and potentially Apple) want out of autonomous car technology? At least, in the short term, their goal is to sell more cars to consumers. What approach fits best with that goal? Incrementalism -- in other words, making sustaining improvements to their existing product to grow sales volumes and average selling prices. And as Jan rightly pointed out, consumers are unlikely to trust the technology behind fully autonomous cars right off the bat. Therefore, striving for incremental improvements in autonomy makes perfect sense for business models dependent on hardware sales.

What about companies like Google and Uber? Each has made a significant investment into autonomous vehicle technology, but neither has any interest in any part of the automobile distribution value chain. Google has famously eschewed the paid software licensing model, so any assertion that Google plans to charge car companies for using its software must be viewed with skepticism. Meanwhile, Uber's business model is entirely aimed at reducing car ownership. An incremental approach (starting with semi-autonomous vehicles) would make absolutely no sense for either company. Why would Uber care about the driving experience of cars on its ridesharing service? What does Google gain from the sales of self-driving cars? Even if Google robot cars rely on Google services, consumers would not.

According to press reports, Google plans to monetize its self-driving car technology through a ride-sharing service which is more consistent with its services-oriented business model. Meanwhile, Uber's goal would be to head-off any potential disruption to its business model, one that relies on the network effect between drivers and riders (fully autonomous self-driving cars -> no drivers -> no network effect -> no competitive advantage). Full autonomy is the only feasible approach here because semi-autonomous vehicles have no impact on the network effects that exist on today's ridesharing services. Google would have no hope of attracting drivers (the fundraising activity of ridesharing companies should give us some hint about the investments required to attract drivers). From Uber's point of view, semi-autonomous vehicles would not pose any sort of defense against the disruptive threat from a ridesharing service with driverless cars. Chasing full automation is absolutely the right approach for service companies because their eventual goal is to disrupt the existing model of car ownership, not to sustain it.

What about trust? Don't consumers still need to trust self-driving car technology to use these services? Yes, but it isn't nearly as important because of the costs involved. The level of trust required to make a $100,000 car purchase is dramatically higher than for a $20 self-driving car ride. There will be no shortage of early adopters willing to try these "low cost" services at least once. Once that barrier is crossed, their popularity will be entirely dependent on rider experience and word-of-mouth. Of course, a positive rider experience is far from a guarantee but that entirely depends on the quality and reliability of the technology and data (in other words, combined driving experience of the algorithm's "hive mind"). Rider experience and word-of-mouth will have little to do with pre-existing notions of consumer trust.

To summarize, my counter argument truly demonstrates the importance of studying a company's business model before assessing the efficacy of its strategy. Analyzing a services company through the lens of a hardware-based business model can only lead to flawed conclusions.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

The State Of Wearables

Publié: janvier 8, 2016, 2:04pm CET par Sameer Singh

I have been skeptical about the mass market potential of wrist-worn wearables ever since Google unveiled Android Wear in 2014. Since then, we have seen a number of high profile smartwatch launches, including the Apple Watch and the recent Fitbit Blaze (which was greeted with an 18 percent decline in FitBit's stock price).

However, the hunt for a killer app continues and I have yet to come across a relevant use case for mass market users.

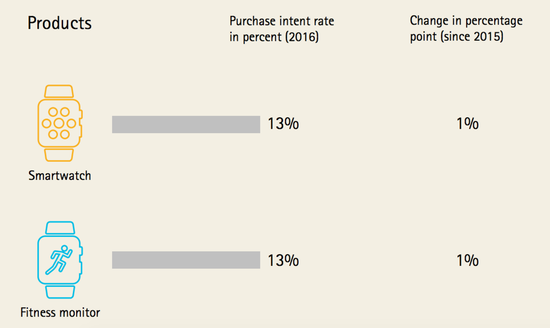

Benchmarking the current state of this product category has been challenging because of the complete lack of reliable, public data. Luckily, Accenture recently released some data that could ease our way. Accenture's survey covers 28,000 consumers across 28 countries and covers consumer interest in devices ranging from smartphones, tablets and laptops to wearables and drones. A few key insights from their survey are highlighted below:

- Only 48 percent of consumers plan to buy a smartphone in the next 12 months, down 6 points from last year. The drop was particularly stark in China, where it went from 82 percent last year to only 61 percent this year. Of those who don't plan to buy a new one, 47 percent said the main reason was because their current phone was good enough.

- Similarly, the survey showed an eight-point drop in purchase intent for tablets, and a six-point drop for laptops. Overall, only 13 percent expected to spend more on smartphones, tablets, and laptops this year than last year. That's compared with 33 percent who said they were planning to spend more in 2014 than 2013.

- Most worryingly, interest in wearables and connected devices was flat from last year, and purchase intent is relatively low.

Unsurprisingly, "good enough" smartphones have had a noticeable impact on upgrade intent. This was something I pointed out two years ago, but in hindsight I called it too early back when industry-wide smartphone screen sizes were still not "good enough". The more interesting takeaway to me is that purchase intent for smartwatches and fitness trackers has not increased despite the high profile product launches, massive ad campaigns and expanded distribution we saw in 2015. With wearable shipments growing sequentially (from an admittedly small base), shouldn't we expect word-of-mouth to have some sort of impact on purchase intent?

Thanks to Endeavour Partners research from mid-2015 (already dated by now), we know that smartwatch abandonment rates continue to be high and this is a key metric to watch. The lack of an obvious value proposition for mass market consumers is a clear drawback and appears to be dampening word-of-mouth. Of course, this data is more backward looking than it appears (as most consumer surveys are). Purchase intent is a function of the value communicated by a product, based on existing capabilities. New capabilities unforeseen by consumers can have a dramatic impact on these responses. But new capabilities are largely a function of app innovation, which has been hampered without access to new contexts or input models.

This is why I have largely based my skepticism not on current smartwatch iterations, but on what they can become in the future.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

YouTube Red: Trigger for cord cutting?

Publié: octobre 30, 2015, 2:01pm CET par Sameer Singh

YouTube announced its first-ever subscription service last week, YouTube Red, with the usual set of (uninteresting) "premium" features -- ad-free videos and offline/background playback. The only interesting tidbit was that YouTube Red would also house "original" movies and TV shows starring well-known YouTube personalities. While it may seem mundane, this move has the potential to present a true disruption to the TV industry.

For years, industry observers have talked about the looming threat of cord-cutting -- consumers were expected to drop expensive cable subscriptions in favor of on-demand streaming services like Netflix. But while Netflix has seen exceptional growth, we are yet to see a tipping point in cord-cutting behavior.

This is because content creators (production studios, sports leagues, etc.) really hold all the leverage in negotiations with distributors (like Netflix). In response, Netflix began producing its own original content. The problem: Netflix was competing against incumbent production houses for the same talent (actors, writers, producers).

As a result, Netflix's originals inherited more or less the same cost structure as Hollywood production studios along with their inherent risks, but with less favorable subscriber economics. This limited the scale of content creation.

Now compare this with YouTube's approach to developing originals. By tapping into their base of homegrown stars and offering a cut of subscription revenue, YouTube's cost structure for content creation could be dramatically lower.

As the share of revenue earned by content creators is a function of subscriber time spent, it could incentivize other YouTube channels to create their own long-form content (30-60 minutes) exclusively for YouTube Red. The resulting scale of "original" content on YouTube Red could eventually rival cable.

In addition to scale, creating a parallel library of premium content also gives YouTube another strategic advantage. Teenagers who have grown up watching YouTube could increasingly gravitate towards long-form content produced by personalities and brands they are familiar with. Long-term, this could decrease interest in traditional movies and TV shows (maybe even sports), leading to real cord-cutting.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

Google's Amazon Problem

Publié: octobre 21, 2015, 9:21pm CEST par Sameer Singh

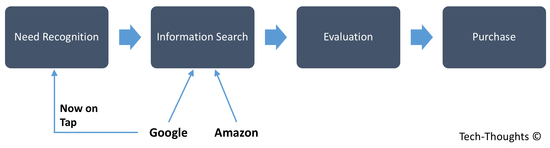

I have long been a critic of the "Peak Google" argument because it is based on a flawed premise -- that deep engagement and consequently "brand advertising" are somehow a threat to Google's model of transactional engagement. While I strongly disagree with that line of reasoning, there are other threats that Google faces within the transactional realm.

Search advertising drives the vast majority of Google's revenue and the most profitable searches are frequently those that are made with the intent to purchase. These purchase-oriented searches are hardly monolithic but can broadly be categorized into B2B and C2B searches. C2B searches can be broken down further into products and services. Looking at taxonomy of transactional opportunities makes it clear that the threat from "deep engagement" is vastly overstated. Facebook is a great place to generate awareness but it's hardly a way to reach customers looking for something specific. Also, breaking down the gamut of transactional opportunities makes it easier to identify threats.

Google doesn't really face a host of challenges in a transactional B2B context (especially valid for high-volume SMB searches, e.g. buying office furniture). On the C2B services side, on-demand startups are a threat but not a major one given the breadth of possible needs (e.g. travel, legal representation, car repair, insurance, etc.). This leaves C2B product searches (e.g. buying a phone). If these searches eventually lead consumers to the same vendor, wouldn't it be more convenient for consumers to "cut out the middleman"? This may already be happening. According to a recent survey, 44 percent of US shoppers go directly to Amazon for product searches, while 34 percent go to search engines (notably, Google). On mobile, where speed is of the essence, it is safe to assume that the percentage of mobile searches would be even more skewed in favor of Amazon.

How could Google possibly counter this threat? Simple; by moving a step back. Google's current transactional model targets users that are already aware of their intent to purchase -- the same users that Amazon targets. But if Google could predict intent, it could reach users one step before they put that intent into action.

This appears to be Google's primary focus with Now on Tap, the tentpole feature accompanying Android 6.0 Marshmallow. In many cases, consumers discover needs through conversations with others and many these conversations happen on smartphones. By inserting themselves into the layer between conversation and action, Google is set to gain a key competitive advantage over other forms of transactional engagement. The fact that this covers both C2B products and services also allows Google to create a defensive moat around their model. This shows how important Android is to Google's future, even though it is not and was never meant to be a standalone business.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.Photo credit: photogearch / Shutterstock

-

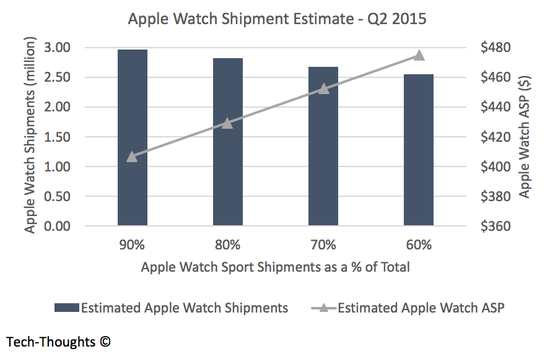

My Apple Watch estimates: 3 million shipments, 2.5 million sales

Publié: juillet 22, 2015, 10:19pm CEST par Sameer Singh

After months of speculation, Apple finally released some vague numbers related to the Apple Watch. As a part of their fiscal Q3 2015 earnings release, Apple announced that revenue from "Other Products" including the Apple Watch, iPod, Apple TV and other accessories totaled $2.64 billion during the quarter. This compares to roughly $1.69 billion in fiscal Q2 2015, before Apple Watch sales began. Combined with some comments from Tim Cook, this should help us get to a rough estimate of Apple Watch shipments (if not sales) for the quarter. We can then also compare this estimate with the third party data sources I highlighted in my last post.

Apple's CFO Luca Maestri mentioned during the earnings call that the Apple Watch was responsible for more than 100% of the sequential revenue growth of "Other Products" because of a decline in revenues from non-Apple Watch products like the iPod, Apple TV and other accessories. If we assume a 15% sequential decline in revenue from those products, we can attribute roughly $1.2 billion in revenue to the Apple Watch.

Things get trickier from here as the average selling price (ASP) of an Apple Watch heavily depend on the product mix between various models. I've assumed that the $10,000+ Apple Watch Edition comprised just 0.1% of sales. Beyond this, the share of the Apple Watch Sport (the cheapest model starting at $349) heavily influences the ASP. If the Apple Watch Sport comprised 60% of overall Apple Watch shipments, the ASP would come it at roughly $475 implying roughly 2.5 million Apple Watch shipments. But if the Sport model took 90% of shipments, the ASP would be below $410 which gives us a shipment figure just under 3 million units. All things considered, 2.5 to 3 million units seems like a reasonable estimate for shipments.

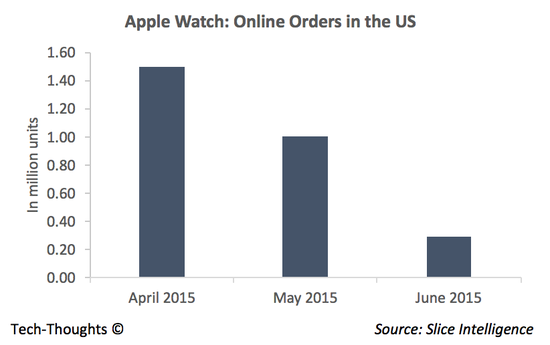

But beyond missing analyst estimates (despite reports of poor sales, some analysts had expected shipments as high as 5 million), this number doesn't mean a whole lot by itself. But it does give us a frame of reference to compare next quarter's numbers and those from third parties. How does this compare to the widely criticized estimates from Slice Intelligence?

Slice had estimated 2.79 million online-only sales (not shipments) through mid-June in the US. Based on Apple's numbers, it appears as though Slice actually overestimated sales by a significant margin. The only other possibility is that sales outside of the US and through retail channels were non-existent. I would normally not discount that possibility, but I have to believe that there was at least an initial burst of sales in China.

But, again, the most important part of Slice's report was the trajectory of sales. Given Apple's reported figures, the initial surge of online orders and subsequent supply shortfall, it is very likely that sales tailed off after launch (with additional retail sales, the overall decline would have been lower than Slice estimated). However, Tim Cook claimed that sales in June were higher than those in April or May. At face value, this doesn't appear to match Apple's reported figures. However, this could be the result of supply ramp up after initial orders outstripped available inventory (credit to @sbono14 for the tip).

Tim Cook also claimed that sell-through of the Apple Watch after 9 weeks was greater than the original iPhone and iPad. For context, iPad shipments totaled 3.27 million in fiscal Q3 2010, roughly 11 weeks after launch. We can reasonably assume that iPad shipments over a 9-week period would have totaled about 2.7-3 million, of which 2.3-2.5 million may have been sold to consumers. Given the constraint of 3 million Apple Watch shipments, 2.5 million should be a reasonable estimate for Apple Watch sell-through. Admittedly, this is more of a "guesstimate", but that's all we have to work with at this point.

If we assume that Slice's pre-order estimates were right (they were consistent with estimates from other analysts), the Apple Watch sold roughly 1.5 million units at launch and roughly 1 million units since then. Of course, this 1.5 million figure refers to online orders and early supply constraints would have ensured that shipments (and revenue recognition or reported "sales") remained below this figure. Even if that pre-order estimate is off, I seriously doubt it would have been below 1 million units (the supply bottlenecks wouldn't make sense if this was lower), which would give us an estimate of roughly 1.5 million sales for the remainder of the quarter.

To summarize, it appears that Apple shipped 2.5-3 million Apple Watches into the channel and roughly 2.5 million may have been sold to consumers. Of these, roughly 1-1.5 million were sold at launch to loyal Apple users and another 1-1.5 million units may have been sold for the remainder of the quarter. This slowdown suggests that word-of-mouth for the Apple Watch has been less than stellar. It is possible that native apps could change this. But given the constraint-benefit trade-off on smartwatch platforms, app development may not be as much of a home run as it seems.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

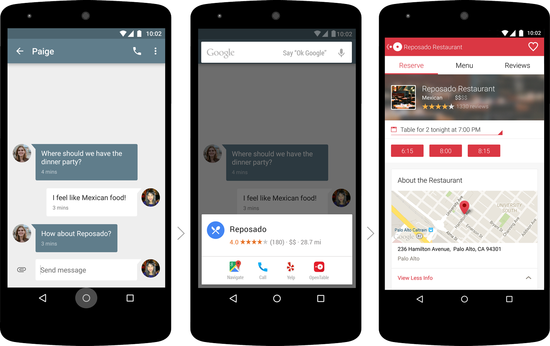

Google Now on tap: PageRank for apps

Publié: juin 19, 2015, 8:31pm CEST par Sameer Singh

Google's implementation of the PageRank algorithm was a transformational moment for the desktop web. In the pre-PageRank era, scouring search directories for relevant websites and manually typing long URLs into a browser's address bar was common. Google's use of links as a "voting" system for discovering websites changed online discovery forever. The app interaction and discovery model prevalent today bears many similarities with the pre-PageRank era of the web, with apps listed under numerous app store categories. Google's Now on Tap may usher in the very "PageRank for Apps" era we have been waiting for.

Before diving into the importance of Now on Tap, let's take a look at how Google describes the service:

We’re working to make Google Now a little smarter in the upcoming Android M release, so you can ask it to assist you with whatever you’re doing -- right in the moment, anywhere on your phone. With "Now on tap," you can simply tap and hold the home button for assistance without having to leave what you’re doing -- whether you’re in an app or on a website. For example, if a friend emails you about seeing the new movie Tomorrowland, you can invoke Google Now without leaving your app, to quickly see the ratings, watch a trailer, or even buy tickets -- then get right back to what you were doing.

If you’re chatting with a friend about where to get dinner, Google can bring you quick info about the place your friend recommends. You’ll also see other apps on your phone, like OpenTable or Yelp, so you can easily make a reservation, read reviews or check out the menu.

When you tap and hold the home button, Google gives you options that are a best guess of what might be helpful to you in the moment.

Today, users discover apps by browsing through app stores or through advertising / social channels and word of mouth. But now, Google is building ability to suggest apps to users based on what they require most at that very moment. In other words, instead of indexing websites and using links as the voting system, Google appears to be indexing apps and using live, in-app information as the voting system. This changes the workflow for users as jumping from app to app becomes much easier and completely cuts the smartphone homescreen out of the equation.

Suffice to say, this has the potential to completely reshape the app interaction model as we know it today. If the service works as expected, launching an app from a homescreen may soon be as alien a concept as manually typing a URL into a browser's address bar.

Of course, this also dovetails perfectly with Google's monetization model. Except for one, Now on Tap gives Google all the required assets to implement an Adwords-equivalent advertising model for the mobile era -- knowledge of user context (instead of keywords) and screen real-estate across all smartphone apps (instead the search page). The only missing ingredient is a contextual bidding system for ads on Now on Tap cards. This seems to be a few years away as well, but the direction of Google's evolution has now become clear.

This also seems to have thrown a spanner into the Peak Google narrative we've heard so much about. This was inevitable as asymmetric business models (like Google's) have been continually misunderstood by pundits. Just as we saw in the case of post-IPO Facebook, critics ignored Google's investments into intermediate products and the assets gained from them. Now on Tap is the clearest possible indication of the latent value held by these assets.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

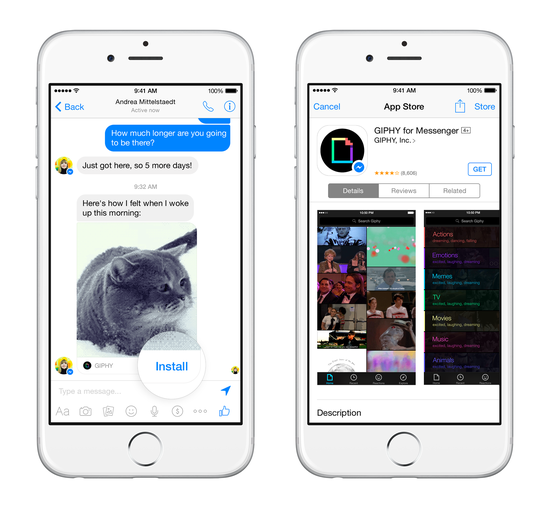

Comparing Facebook's and Google's vision for mobile

Publié: mars 27, 2015, 1:15pm CET par Sameer Singh

On the first day of the F8 developer conference, Facebook finally pulled the trigger on something we had expected for months. Facebook messenger is now a platform along the lines of WeChat and other Asian messaging apps. While this isn't necessarily "novel", it tells us something about Facebook's vision for mobile.

Facebook announced the SDK for messenger along with the fact that 40 apps, including ESPN, Dubsmash, and Talking Tom and Giphy had already signed up for the program. Their willingness is simple to explain -- app stores have fixed the app distribution problem, but have consequently made app discovery far more difficult. Easy app distribution and low entry barriers have created a deluge of app developers with more than a million apps and counting. But with these numbers, app developers have found it increasingly difficult to reach consumers through all the noise. This is where Facebook Messenger comes in:

Messenger Platform apps can display the option for a person to install the app from within Messenger, or to reply using content from the app. If the person receiving the message doesn't already have an app installed, they can tap Install to be taken directly to the app store to get started using the app. This means people can discover apps recommended by their friends, naturally through their conversations.

With Messenger Platform, developers may also see increased app engagement: If the person receiving the message already has the app installed, they'll be able to tap Reply on an image in a message. Then, instead of scrolling through pages of apps on their phone, they'll be taken directly to the app to reengage and respond with relevant content.

In essence, Facebook seems to be implementing natural "links" between apps, i.e. user interactions flow from app to app, much like the desktop web. Facebook's vision seems to rely on their network of users and their social interactions to solve the app discovery problem. This presents an interesting contrast with Google's vision -- an algorithmic to present the right information in the right context. It's no surprise that each company's vision is entirely built on their inherent strengths. But I'm actually starting to think that their contrasting approaches are much more complementary than they might appear.

On a simplistic level, both Google and Facebook are direct competitors because they build mobile services and generate revenue from advertising (made more valuable because of data-driven targeting). While this is true when it comes to monetization, each company follows a very different approach to craft a value proposition for their users. Google follows an algorithmic and data-driven approach to organize and provide users with information (e.g. Google Maps, Search, Google Now). In contrast, Facebook's approach is less data driven and more reliant on enabling social interactions between users. Once you look at the two companies through this lens, it actually seems as though both visions are somewhat complementary. Gathering information is just as important as spreading it.

Extending this argument to app discovery, social vs. contextual discovery may fit different kinds of apps. It's no surprise that most of Facebook Messenger's initial partners are publishers or content-based apps. Social discovery seems to fit these kinds of apps like a glove. On the other hand, apps that are more transactional in nature (on-demand transportation, or anything that involves mobile commerce) are likely to favor a more algorithmic approach (a user is more likely to use Uber/Lyft when he lands at an airport, irrespective of his/her social interactions).

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

Google, mobile and the next billion

Publié: mars 1, 2015, 12:45am CET par Sameer Singh

The change in Google's narrative over the past few months has been very interesting to watch. The recent "Peak Google" proclamations remind me of Facebook's post-IPO narrative in 2012. Conventional wisdom back then was that Facebook's decline was imminent as mobile was not a meaningful part of their revenue. Of course, Facebook's app install ads and other mobile initiatives disproved that narrative in short order.

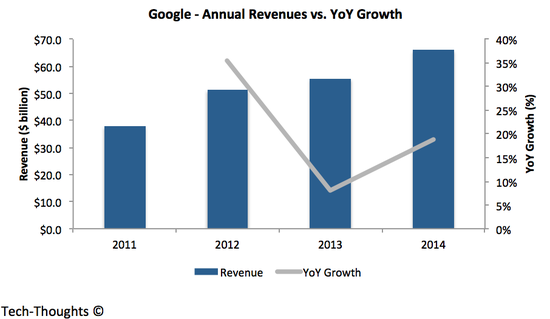

Some observers even make it seem as though Google's growth has seen a major slowdown in 2014. Interestingly, both Google's revenue and operating profit growth accelerated in 2014. This isn't to say that mobile does not pose a challenge to Google. It does, but it is important to understand exactly what those challenges are and the way forward. By looking at Google's financial reports, their biggest challenge is a decline in operating margins. This has been triggered by increase in search advertising on mobile, which delivers lower CPCs. While consumers used search on PCs for more involved research on products/services, the interaction window for mobile search is shorter. Lower ad engagement led to fewer bids on keywords and consequently, lower CPCs and margins.

While there has been talk of "brand advertising" being the next big opportunity on mobile, a look at Facebook's mobile growth suggests that transactional opportunities remain massive. Facebook used app login data to create a targeting engine for app install ads, which drove a significant portion of their growth on mobile. As the app economy continues to grow and extend its economic influence beyond app store revenues, app install (or engagement) ads will remain a lucrative opportunity on mobile. This is one area where Google has been a laggard, even though they clearly have the assets (app usage data, access to developers/brands, Google Play, Google Now) to be a market leader.

Unsurprisingly, we now have evidence that Google has not been ignoring this opportunity -- the company just announced the launch of app install ads on Google Play. In my opinion, this is Google's first step towards a major opportunity, i.e. contextual app install or "access" ads implemented via Google Now.

This should provide a counter-argument to one segment of the current narrative surrounding Google. I have also heard another, more puzzling argument that goes something like this -- The next billion smartphone users will experience the internet for the first time. These users (e.g., a farmer in Africa or India) will have very different needs and far lower purchasing power, which could challenge Google's business model. It's not that I don't agree with this argument, I do. It's just that this argument is applicable to every tech giant in the world, from Google to Facebook to Tencent. These consumers may use Google search, Facebook, Whatsapp or a host of other apps. But they aren't valuable to Google or Facebook's advertisers and they aren't likely to be major in-app purchasers. How exactly are WeChat or Snapchat going to monetize these users? The answer I hear most often is "services". But which services? And how will they be monetized?

In my opinion, there are business models that could cater to this segment (e.g. monetizing usage data directly through by-products of usage), but they seem to fit smaller services companies like Duolingo or Opensignal. As a result, I expect to see a split in companies that cater to today's mass-market consumers and those that cater to "the next billion". And that isn't necessarily a risk for today's tech companies (for now) because these monetization models also require very different businesses.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.Photo credit: ljh images / Shutterstock

-

There is no smartwatch market

Publié: février 13, 2015, 3:19pm CET par Sameer Singh

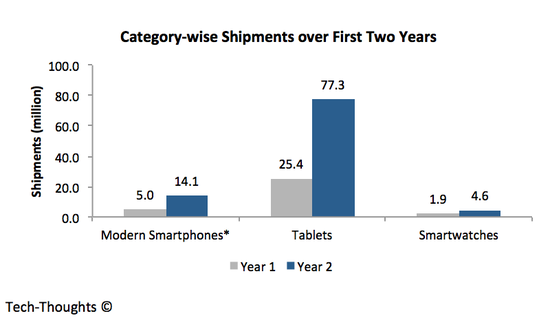

A few months ago, I wrote a post comparing the early sales of smartwatches to those of tablets and modern smartphones (early iPhone and Android models). As I expected, the numbers didn't bode well for smartwatches. Now that we have another year's worth of data to play with (from Canalys this time), we have an opportunity to test the validity of my previous analysis.

The chart above plots smartwatch shipments against smartphone and tablet shipments for two years after the point when each category was meaningfully conceived. Data on smartwatch shipments has been combined from multiple sources including Canalys, Strategy Analytics and ABI Research. Now compare this updated chart with my previous observations.

The first observation from the chart is that early tablet shipments dwarfed those of modern smartphones and smartwatches. But even modern smartphone shipments more than doubled those of smartwatches. The smartphone-tablet dichotomy is fairly easy to explain. The iPhone and other modern smartphones relied on a completely new interaction model (capacitive touch and multitouch) which most consumers had never used before. In addition, this was in the "pre-appstore" era when software distribution was still unclear. By the time tablets were unveiled, both consumers and developers were comfortable with the interaction model and appstores, i.e. tablets had no real learning curve.

In some ways, smartwatches have had the same advantages that tablets enjoyed. The interaction model doesn't seem drastically different (compared to the transition from keyboard/mouse to touch) and appstores are well established. They also benefited from Samsung's offer of a free Galaxy Gear with the Note 3 phablet. Despite these advantages, smartwatch shipments have remained well below those of early smartphones and tablets.

It is clear to me that smartwatch technology has improved significantly over the past year. But the fact that this has had no impact on consumer adoption should be worrying. It is becoming increasingly clear that the use cases targeted by smartwatches (at least today) are primarily valued by a niche segment of technology enthusiasts. The list of questions about wearables, seems to be getting longer, but we are no closer to finding answers.

Update:

- The data in my chart includes all wearable wristbands, including fitness trackers. If we drill down to just smartwatches like the Pebble and Android Wear devices, year 2 shipments drop to around 1.5 million.

- The measurement period begins when products relying on the dominant interaction models are introduced to the market, i.e. a touch interface that does not require a stylus for smartphones / tablets. App developers play a major role in discovering use cases, but those still depend on the advantages and drawbacks inherent to the interaction model. Would Angry Birds be a viral hit if users had to fiddle around with a keypad? With this context, it may even make sense to exclude Pebble shipments to make a more accurate comparison (<1 million in Year 2).

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

The potential and pitfalls of HoloLens

Publié: janvier 22, 2015, 10:31pm CET par Sameer Singh

Microsoft made some long expected announcements today -- the return of the start menu, one version of Windows 10 across all devices and an attempt to make Windows apps work across those same devices. Unfortunately, the limited overlap between Windows PC developers and mobile developers makes the latter a weak proposition. On the other hand, Microsoft's HoloLens headset may have some potential.

I have long been a believer in the long-term potential of "field of vision" devices (AR and VR) for one simple reason -- despite their downsides, their potential benefits cannot be matched by existing computing platforms. In my opinion, this is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for triggering a new market disruption. While we are still in the early stages of the technology (think first mobile phone, not first smartphone), I believe we could see increasing consumer interest in this category over the next five years.

Looking at HoloLens specifically, it holds a couple of advantages over other field of vision devices we have seen so far -- 1) It is not meant to be mobile (at least for now) so social acceptance will not be a barrier, 2) It blends elements of augmented reality and virtual reality. The second point is particularly interesting as it falls between the "glance" based interaction model targeted by Google Glass and the complete immersion provided by Oculus. By allowing users to interact with virtual, 3-dimensional objects (not really holograms) in their surroundings, Microsoft is exploring a truly novel interaction model here. Another good sign is that hands-on experiences of the device from enthusiasts and the press seem fairly positive. Increasing awareness could help attract developers that are interested in exploring new interaction models. All in all, it seems like Microsoft is going in the right direction with this technology.

That said, there are some very obvious pitfalls here for Microsoft. Since this isn't meant to be a "mobile" device, it could potentially be used in conjunction with other devices. Microsoft showed off this particular use case in the "Mars demonstration" -- Users on their PC could move their mouse cursor "off screen" to interact with the virtual environment. There may be a temptation here to link the HoloLens technology (or platform) with Windows to increase developer interest on their mobile platforms. That could immediately shrink an already small early adopter base and cause mobile developers to look at options like Oculus and Magic Leap. But as long as Microsoft plays their cards right, they may be on to something here.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

Expanding on 'New Questions in Mobile'

Publié: décembre 12, 2014, 11:14am CET par Sameer Singh

Benedict Evans recently wrote an insightful piece exploring new questions for the mobile industry. Among the five questions he brought up, I believe that the evolution of interaction models and messaging will end up being the most important.

I don't have anything to add there as think Benedict's analysis here was excellent. However, I do think that three of his questions could benefit from deeper analysis. I also think that he may have missed a crucial question brought on by the scale of the mobile industry.

What Is Android Going To Be?

This is a very popular question among some industry observers. Benedict's assertion here is that Google's control over the Android platform isn't guaranteed as the appeal of Google apps is limited and user engagement with Google Play is lower than that on iOS. As I argued in the AOSP Myth, this may be a weak argument. In a hyper-competitive industry, it is very difficult for a "Google-free" OEM to compete if 5-10 other OEMs are selling the same device, at the same price, with Google services. This is why China is a bit of a red herring -- there aren't really any devices sold in China with Google services.

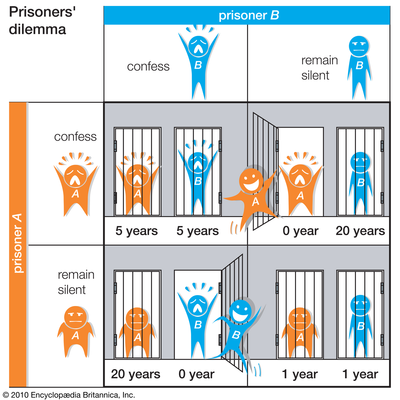

The easiest way to understand this is through an economic concept called the Prisoner's Dilemma:

As per the classic example, two prisoners are interrogated individually and are given the opportunity to betray the other or remain silent. The "payoffs" are as follows:

- If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves 5 years in prison

- If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve 20 years in prison (and vice versa)

- If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison (on the lesser charge)

In effect, the best payoff for both prisoners will be achieved if both remain silent. But the best individual payoff requires each to betray the other. So the only rational course for any self-interested party (like profit-generating enterprises) is to betray each other. In the case of Android OEMs, it may benefit the whole industry (from a differentiation and profit standpoint) to fork Android and exclude Google services. But the threat of selling a non-competitive forked device, while others sell devices with Google services is too great for this to ever happen. Therefore, the only option left is to continue selling compatible, Google-licensed products. With this background, it should come as no surprise that Chinese OEMs (even those with customized firmware, like Xiaomi) have continued to rely on Google services outside China.

Forking becomes even more problematic from an ecosystem viewpoint. As Visionmobile explains in "The Naked Android", Google has been pulling core APIs away from open source Android for years. Many of these APIs, including location services, billing, C2D messaging, syncing, etc., are now housed under the licensed Google Play Services umbrella. This means that any prospective "forker" will have to replicate these APIs and convince app developers to build customized variants of Android apps for their user base. Unfortunately, the install base of these prospective "forkers" never justifies the incremental cost for app developers, which automatically makes their business model unviable. This is why Xiaomi continues to emphasize that MIUI is a "compatible fork". Could we see more forks in the years ahead that are compatible with Google services? Of course, but that isn't necessarily against Google's interest.

This isn't to say that Google would never merge Android and Chrome. That could certainly happen, but it will probably be driven by the evolution of interaction models and not the threat of forking.

Facebook and Amazon

One assertion Benedict makes here is that Amazon and Facebook are motivated to insert themselves between users and platform owners, but haven't yet been able to. The first half of that statement is certainly accurate, but the second half isn't necessarily true. Benedict's analysis here is restricted to high profile failures like the Fire Phone and Facebook Home.

While Amazon hasn't had much success here, Facebook has. Integrating Facebook login with Android and iOS apps has helped it collect usage data that is monetized through targeted app install ads. In other words, Facebook has in fact facilitated and monetized app discovery by inserting itself between platform owners and users. App install ads are now a significant revenue driver for Facebook -- a revenue opportunity that Google is still trying to capture.

Wearables

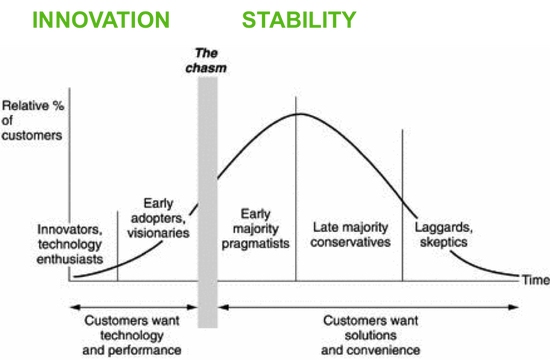

Benedict's point here is that wearables are end points for cloud services and that watches are largely messaging and notification devices. I agree that wearables are meant to be end points for cloud services, but it is still very unclear how mainstream users will (or won't) use these technologies. Messaging and notifications are useful benefits when looking at the market from an early adopter's viewpoint, but it is still unclear if these use cases are necessary (or even valid) in the mass market. The diffusion of innovations can help shed some more light here:

Innovators and early adopters are normally drawn to novel technologies, but these products eventually "fall into the chasm" unless they evolve to solve real problems for mainstream customers. For example, smartphones evolved from being fancy, touchscreen phones to full-fledged pocketable computing devices. At this moment, wearables and smartwatches are at the far left hand side of this curve. Early consumer interest in these devices is mostly driven by the technology, the companies behind these products and specialized use cases. What is still unclear is the primary benefits of these products for the "non-tech savvy" or their potential to become full-fledged computing platforms. This is why the list of questions for wearables is much longer than this one.

As I wrote in "Imagining The Next Big Platform", I certainly agree that devices like Oculus have much more potential to make much more fundamental changes to the basic touch-based interaction model. But this is still many years away for mainstream users (probably even more to the left on the diffusion chart).

Scale & Business Models

Benedict did touch upon scale in his post, but I think he missed a crucial question here. There are close to 2 billion smartphone users today and that will grow to roughly 4 billion over the next few years. However, the purchasing power of these users will be far lower than that of the existing user base, i.e. they will probably buy $25-$50 devices and not $600 or even $200 devices. How do you monetize a user who can only afford to pay $25-$50 for a phone?

At these price points, hardware margins will be razor thin, so companies will have to rely on a services-based monetization model. But even existing monetization models for apps and services will need to evolve to capture value from these users. These users are unlikely to have credit cards and even with carrier billing, their purchasing power may not be strong enough for in-app purchases to be meaningful. Advertising could add some revenue, but how much will advertisers pay to reach a user at these income levels? Therefore, technology companies will have to explore novel business models that purely rely on vast user numbers to profit from mobile scale. Discovering these business models over the coming years will be the most exciting part of studying this industry.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Photo Credit: xavier gallego morell/Shutterstock

-

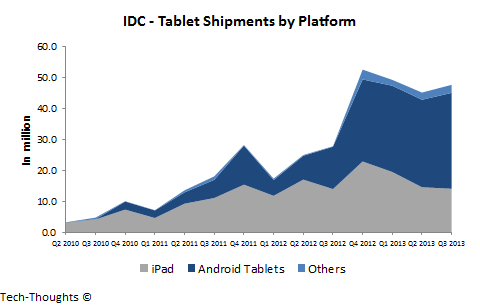

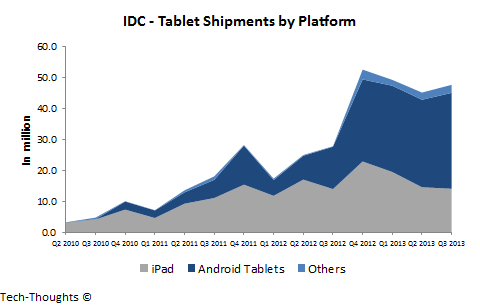

Tablets: Quest for the enterprise

Publié: octobre 18, 2014, 2:15am CEST par Sameer Singh

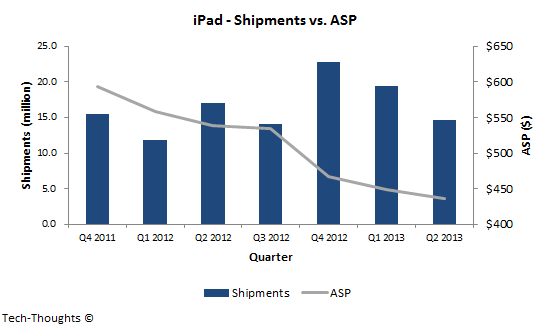

Yesterday, Apple announced a minor refresh to their iPad portfolio, with improvements mostly focused on Touch ID and a thinner footprint. In many ways, this did feel like this was a "placeholder" upgrade. The new iPads would certainly appeal to loyalists, but they don't seem to target the primary reasons behind the recent slowdown.

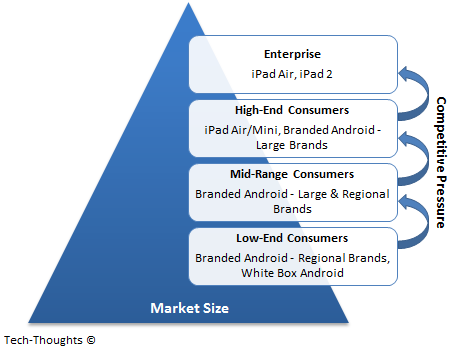

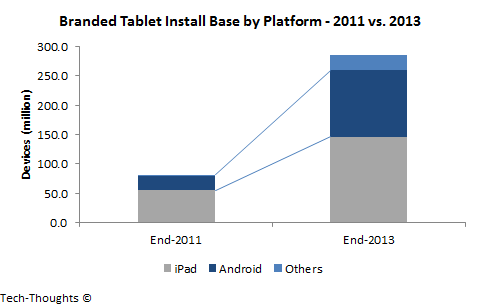

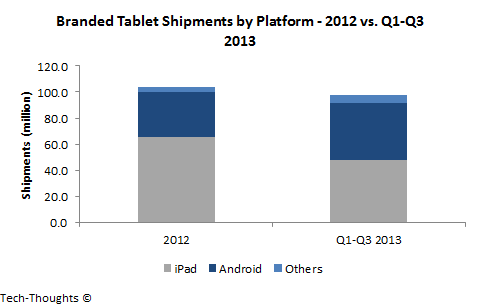

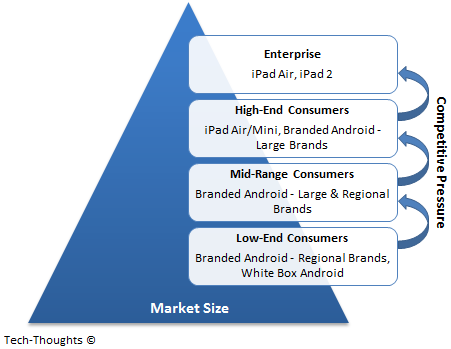

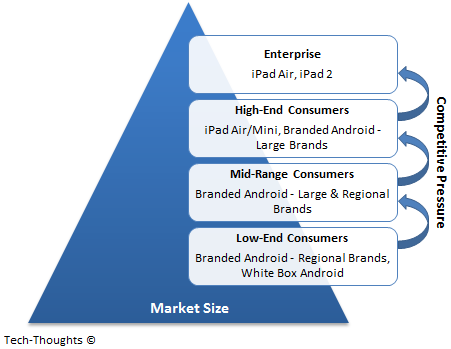

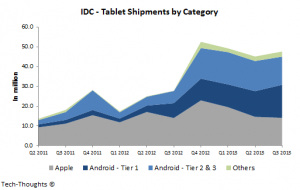

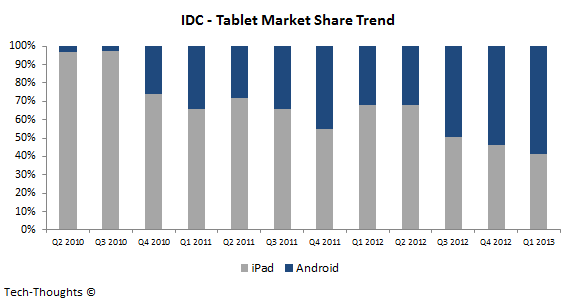

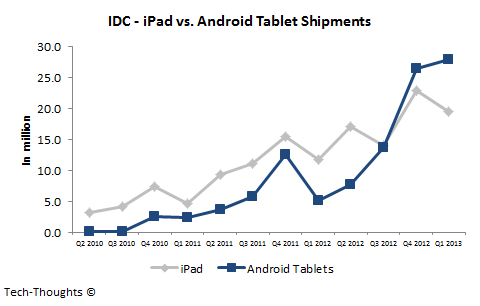

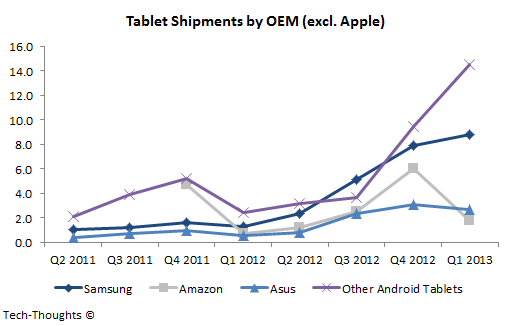

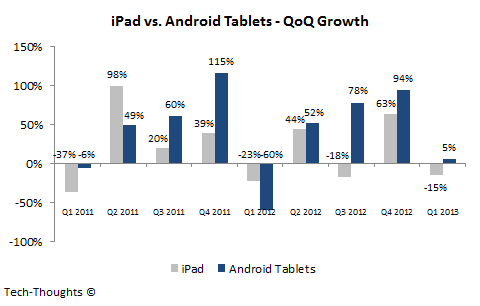

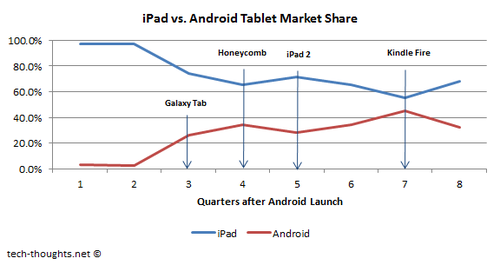

The slowdown in iPad sales (or high-end tablet sales, in general) was caused by three factors -- 1) Increasing overlap in use cases of large screen smartphones (or phablets) and tablets, 2) Inability to move downmarket, despite lower iPad Mini prices, because of competitive reasons highlighted in the chart above, and 3) Limited upmarket mobility because of a lack of developer focus around productivity.

With the release of the iPhone 6 Plus, the first factor really plays into Apple's hands. If you have to cannibalize your own products, doing it with a higher margin product is the most painless way to go. The second factor is a market reality and there is little Apple or any other company can do about it. This leaves an upmarket move as the last remaining option to boost tablet sales. While Apple's IBM deal could help here, that is only a small part of the solution.

In the enterprise, tablet use is still restricted to highly specialized use cases -- executives use them to take down notes, check email, etc. and sales staff in the field use them on the go. The primary issue is that developer innovation focused on tablet productivity has been minimal so far. Developers are partially to blame here because smartphones seemed like the more lucrative market. But OEMs and platform owners have to share some of the blame as well.

Of all the tablets and platforms released so far, only the Surface Pro seemed to target productivity. Unfortunately, Microsoft made major sacrifices in ease of use and pricing to get there. Combined with their ecosystem handicap, this created a compromised tablet and PC experience. On the other hand, Google seems to have taken a step in the right direction with the Nexus 9's keyboard cover. While the Nexus 9 is unlikely to see meaningful sales, it could have a very "Nexus 7-like" impact. So far, tablets with keyboard attachments have remained a novelty. But if more OEMs go that route, it may finally pique developer interest in taking advantage of these accessories. In much the same way, I think Apple needs an iPad Pro to get developers to take an interest in productivity. In my opinion, this may be the only way to meaningfully increase tablet penetration in the enterprise.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

Windows 10: Needed, but business model challenges remain

Publié: octobre 2, 2014, 7:40pm CEST par Sameer Singh

This week, Microsoft unveiled a long-awaited update to its operating system -- officially dubbed, Windows 10. Microsoft says that Windows 10 is an attempt to create a single operating system that works across phones, tablets and PCs, without the compromises that were visible in Windows 8. This is certainly a much needed update that should help them retain their core customer base, but it also doesn't do much to cover up their biggest weaknesses.

First, let's point out the obvious. Microsoft's decision to skip a version number is curious. While Microsoft claims it was because Windows 10 was a "leap" forward, it is clearly an attempt to clear away the hostility faced by Windows 8, especially among enterprise users -- Microsoft's most important customers.

While Windows 8 attempted to fuse two entirely different operating systems (and interaction models) together, Windows 10 seems to select the interaction model most suited to the available hardware. As a result, desktop users (and more importantly, enterprise customers) are no longer forced to deal with a touchscreen interface. It is these customers that Windows 10 is targeted at. This is certainly good news, but it only targets users at the very top of the computing pyramid. Of course, this top tier is defensible as long as the tablet's upmarket mobility remains limited. But lower tiers of computing remain a major challenge for Microsoft.

At lower tiers of the computing pyramid (mainly characterized by consumption, not productivity), Microsoft still faces two major business model challenges. The first is that Microsoft's primary monetization model, software licensing, is no longer feasible. Android has become the de-facto standard for mainstream tablets/smartphones and is available for free. In response, Microsoft made Windows free for devices with screen sizes of nine inches or below. This may seem like an arbitrary cut-off, but it highlights a clear delineation between Microsoft's core and non-core markets (as they see them today). Microsoft has been unsuccessful at monetizing consumer services, so the goal of this move may be more subtle.

My guess is that Microsoft is attempting to subsidize Windows at lower tiers in the hope that it helps defend Windows at higher tiers. The thought is that a Windows phone or tablet user may be more inclined to remain within the Windows ecosystem. This brings us to the second challenge -- Windows doesn't really have a cohesive ecosystem. The app ecosystem Windows phones/tablets is sparse and that limits its appeal to a niche, price-sensitive segment and one that is unlikely to be valuable to Microsoft at higher computing tiers. The ecosystem for a Windows PC consists of very few applications or services that are valuable on a smaller Windows-specific device. As a result, the value of staying "within the Windows ecosystem" across computing tiers is very limited. As of today, these challenges don't pose an existential threat to Microsoft but that may not always be the case. To their credit, Microsoft seems to recognize this. Satya Nadella's emphasis on cross-platform productivity suggests as much.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

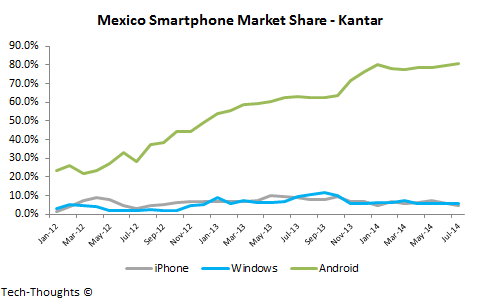

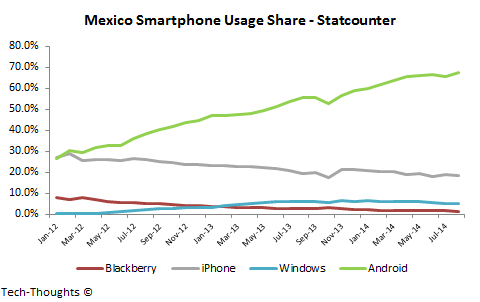

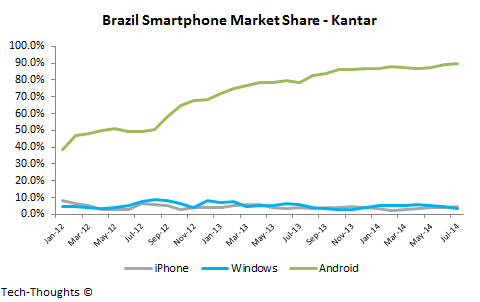

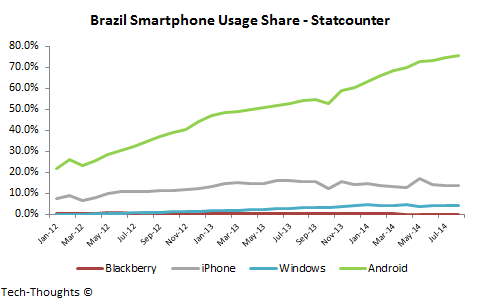

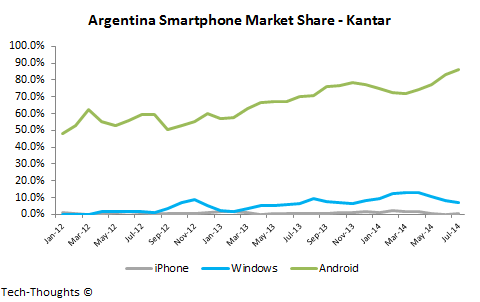

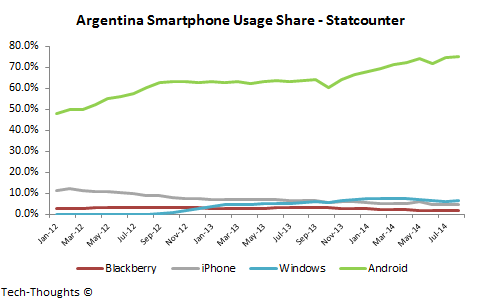

Smartphone market share and usage by country

Publié: septembre 20, 2014, 9:30am CEST par Sameer Singh

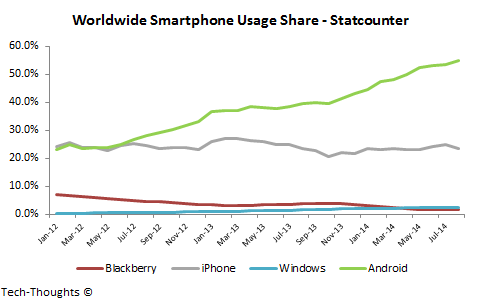

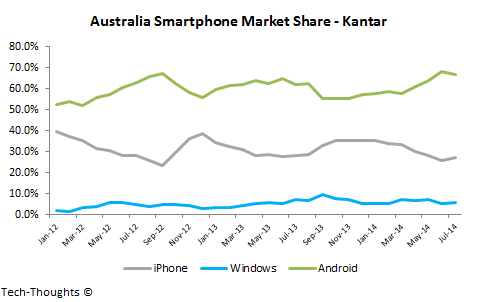

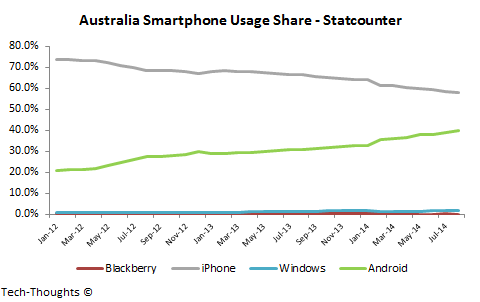

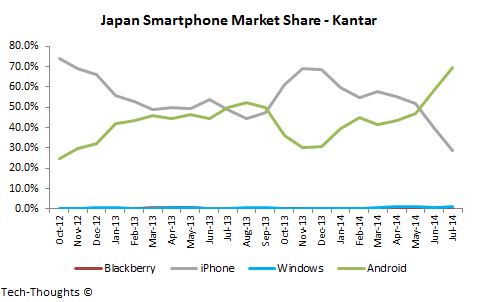

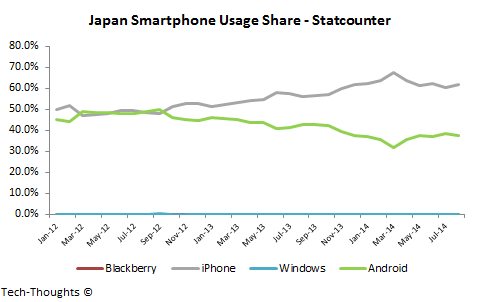

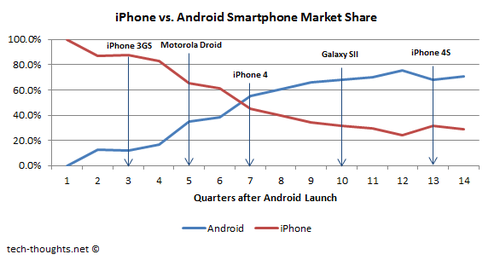

With the arrival of the iPhone 6 (and 6 Plus), this may be a good time to review smartphone market share and usage share trends around the world. As these data points reflect the tail end of the iPhone's product cycle, we should expect a market share bounce over the coming months. On the other hand, movements in usage share are unlikely to be as sharp.

As always, market share data is sourced from Kantar and usage share data is from Statcounter. My rationale for using these particular metrics was laid out in my last post on the topic:

Because of the regionally fragmented nature of distribution, some view global market share figures with cynicism. My argument was that market share patterns by country could give us a better understanding of these trends. While market share of shipments is certainly a leading indicator for install base (and consequently, usage), it only gives us a part of the story. Contrasting regional market share and usage share (as a proxy for install base) may give us an even better understanding.

Usage share (or browsing share) isn't an ideal proxy for install base as it could be skewed towards higher end devices. However, trends in usage share could give us a fairly good understanding of the underlying install base.

While this is only helpful for countries where both sets of data points are available, there are few major markets that are excluded (India and South-East Asia being notable exceptions). Now, here are the metrics for each country.

The Big Two

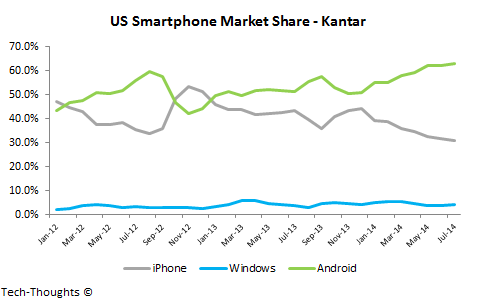

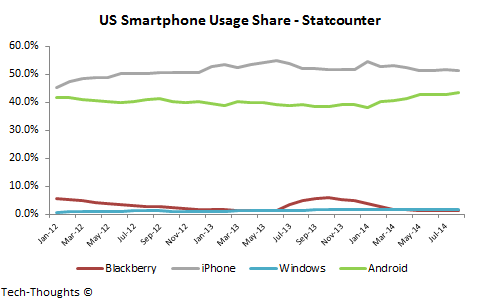

US: Android Hits New High Ahead of iPhone 6 Launch

As expected, the iPhone saw a cyclical decline ahead of the iPhone 6 launch. But the chart also shows that the iPhone's market share began declining YoY in late-2013. This suggests that T-Mobile's and AT&T's unsubsidized "value plans" have had some impact. This combination of factors has led to Android hitting an all-time high in both market share and usage share. The iPhone 6 launch will certainly have an immediate effect on this trend. It will be interesting to watch the scale of this impact.

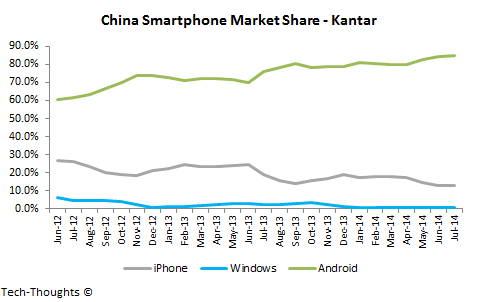

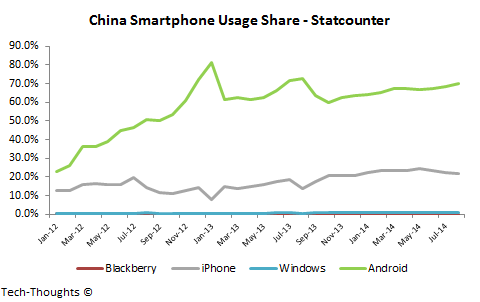

China: Lucrative Market for iPhone, Android Dominates Volumes

In terms of pure volume, the Chinese market has been dominated by Android (or AOSP, as some prefer to call it) for years. Of course, China is the largest smartphone market in the world by such a large margin here that it is lucrative to even be a niche player here. This brings us to the iPhone -- The iPhone has continued to lose market share to Android, mainly because of massive volume growth at lower price points. However, both the iPhone and Android have increased usage share at the expense of legacy platforms like Symbian. The iPhone has seen a notable drop in market share and usage over the past few months, but this came at the end of the iPhone 5S product cycle.

Europe

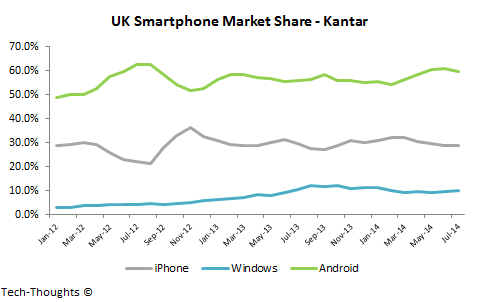

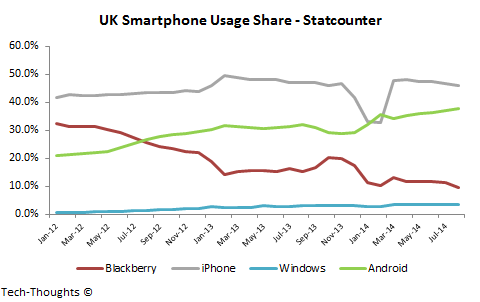

UK: Android Usage Continues to Climb

Over the last few years, the UK has been one of the most predictable markets in the world in terms of market share. It is one of the iPhone's strongest markets across the globe and is quite cyclical as a result. Usage share, however, is a different story. The iPhone's usage share has remained roughly flat over the past couple of years. Meanwhile, Android has seen its usage share double over the same time frame. I have to wonder if this has been caused by increased uptake of high-end Android devices or an outcome of increasing quality at lower price points. We should be able to figure this out based on the impact of large screened iPhones.

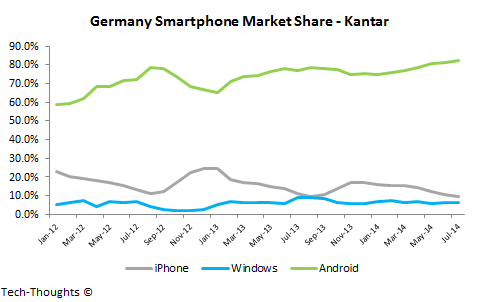

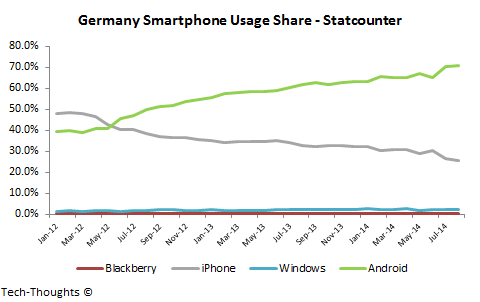

Germany: Business as Usual

The charts paint a pretty clear picture. No explanation necessary. The iPhone 6 launch should tell us if this is purely driven by screen size or if there are other factors at play.

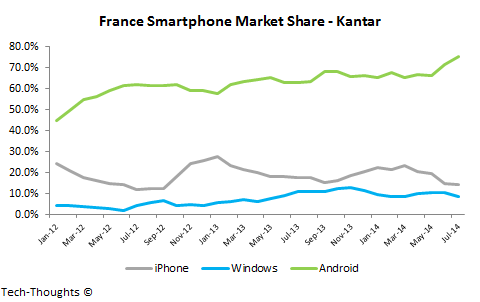

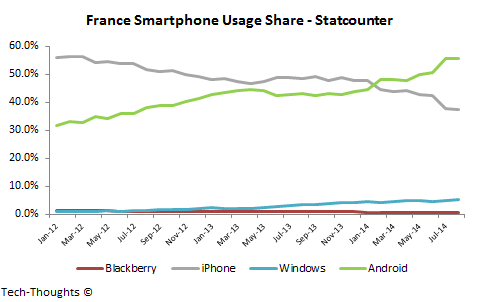

France: iPhone Sees Cyclical Decline, Windows Phone Remains Alive

The iPhone has seen a notable decline in market share over the last few months, owing to the upcoming iPhone 6 launch. Interestingly, Android's usage share overtook the iPhone's in Q1 of this year, after the iPhone 5S launch. Large screened devices typically encourage more browsing, so it will be interesting to watch the impact of the iPhone 6 and 6 Plus. This has also been one of the few markets where Windows Phone shows up on both the market share and usage share charts. While its market share performance has fluctuated, its usage finally cracked the 5% mark.

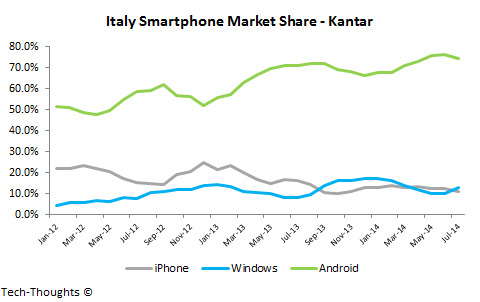

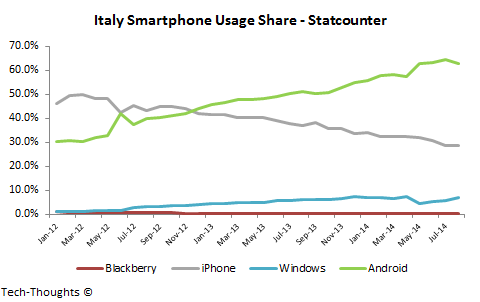

Italy: Android Leads, Followed by iPhone and Windows Phone

The iPhone has never been a particularly strong player in Italy, but it is interesting to see the lack of a pre-launch decline. Android has dominated market share for a few years now, but Windows Phone appears to be staying alive at the ~10% range. In August, it even managed to chip into Android's usage share lead, which is no small feat for a third player. That said, both market share and usage share patterns suggest that this may be Windows Phone's ceiling.

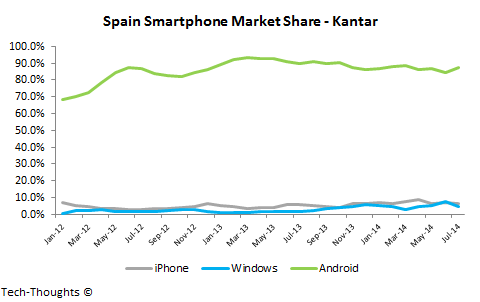

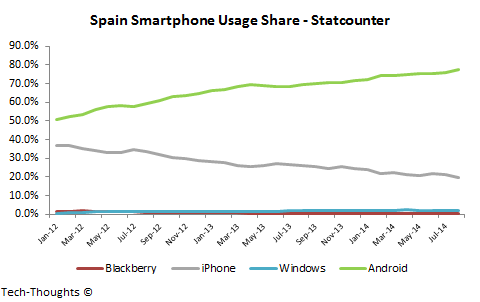

Spain: Germany Revisited

Again, these charts tell the story.

Australia & Japan: Cyclicality Rules the Day

Australia

As in the UK, market share patterns in Australia have remained stable for a couple of years now. As with any other iPhone stronghold, market share is incredibly cyclical. Interestingly, the usage share chart couldn't be more different as Android's share has doubled at the expense of the iPhone. This is another market to watch to gauge the impact of large screened iPhones.

Japan

Japan is one of the iPhone's strongest markets. It is also the most cyclical and most predictable market on this list. This isn't very surprising given that carriers dominate distribution and maintain opaque pricing. Consequently, the iPhone's peak market share and usage share have grown with the number of distribution partnerships with carriers.

Latin America: Android Territory

Again, the charts tell the whole story in Latin America. Both market share and usage share patterns are remarkably consistent across countries.

Mexico

Brazil

Argentina

Photo Credit: glossyplastic/Shutterstock

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

Uber, self-driving cars and Google

Publié: septembre 6, 2014, 1:30pm CEST par Sameer Singh

This is a topic I've briefly discussed on Twitter and then again on Bernard Leong's podcast, but I think it deserves a deeper look. Many are excited about the potential of Uber integrating with self-driving cars. But in my opinion, self-driving cars could be disruptive to Uber's current business model. Let's take a look at a few facets of Uber's business model and gauge the potential impact of Google's self-driving cars.

As I've mentioned previously, Uber is a platform that connects transportation providers (or drivers) with potential customers. Self-driving cars completely remove drivers from this equation and could force Uber to own and manage their own fleet. With their current model, Uber operates with "zero capex" and their marginal cost for adding supply is effectively zero. But by owning self-driving cars, this marginal cost becomes a meaningful amount, i.e. the cost of each vehicle. With this revised cost structure, the value of Uber's business model changes completely.

Of course, taxi companies and other logistics firms could potentially acquire self-driving cars and use Uber to recoup their investment. This could retain the character of Uber's business model. But as Mark Miller mentioned on Twitter, entrenched interests like unions could prevent that.

All things considered, Google's self-driving cars seem to be a real threat to Uber. How does this play into Google Ventures' investment into Uber? In my opinion, Google's investment is a hedge against the regulatory risks faced by self-driving cars. With self-driving cars, Google's vision is to make transportation as easy as an online service and reduce car ownership (this also gives people more time to use Google services). In many ways, Uber accomplishes the same goal but it also has bigger plans to disrupt the logistics industry.

Image Credit: iQoncept / Shutterstock

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

-

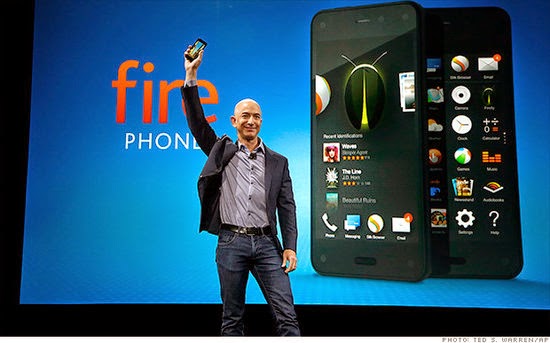

Amazon's Fire Phone is a puzzle

Publié: juin 19, 2014, 6:11pm CEST par Sameer Singh

I've gone back and forth on the prospects for Amazon's smartphone, and yesterday's launch of the Fire Phone hasn't really helped me make up my mind. Apart from the heavily rumored 3D interface, most of what Amazon announced was a surprise to me. It's difficult to ignore the fact that Amazon holds some distinct advantages, but there are also certain areas where they seem to be fighting an uphill battle.

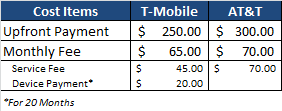

Amazon's Challenges: Pricing and Dynamic Perspective

Let's begin with the obvious, the pricing. Amazon's pricing strategy for the Fire Phone is very similar to those of other premium smartphones -- $650 unsubsidized and $199 on contract. This is especially curious given that the device is exclusive to AT&T, a carrier that has made it a priority to shift to unsubsidized, financing plans. Of course, it's entirely possible that Amazon has given AT&T a subsidy waiver. In this case, the potential of Prime users on heavy data plans could be considerably attractive to AT&T. But this is just speculation on my part.

Another challenge is that the Fire Phone's heavily emphasized differentiator (the 3D interface or Dynamic Perspective as Amazon calls it) may not be much of a differentiator at all. The Fire Phone's market penetration is unlikely to be high enough to spur a large number of developers to leverage it in a meaningful way. This would limit the value of Dynamic Perpective to the device's UI. For the sake of argument, let's assume that consumers find it valuable. This is by no means a given, but if it does happen, what stops other premium OEMs like Apple and especially Samsung from using this feature?

Amazon's Advantages: Mayday and Firefly

The Fire Phone certainly faces a host of challenges, but it holds some distinct advantages as well. The first is Mayday, Amazon's one-tap access to customer service (via video chat). Amazon's customer service is really unparalleled and there are few companies (if any) that could attempt to offer a 24-hour video chat service with a 15 second response time. This could be very useful for technology laggards and first time smartphone buyers. However, this proposition would have been far more valuable if the pricing strategy catered to that segment.

Firefly is another interesting feature that will be difficult for other firms to replicate. It is effectively a camera-driven, real-world search engine which hooks into Amazon. In other words, a customer could look at a product in a physical store and buy it on Amazon within a few seconds. In a way, it attempts to use Amazon's product range and credit card database to make mobile payments unnecessary.

The primary goal of the Fire Phone is to support Amazon's e-commerce business model and this partly explains why Amazon went the premium route -- Premium smartphone buyers are likely to make more online/offline purchases. However, high-income customers can only use Firefly if they end up buying the phone.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

Surface Pro 3: niche product, not a savior

Publié: mai 22, 2014, 4:11pm CEST par Sameer Singh

This week, Microsoft unveiled the Surface Pro 3 with a larger, 12 inch display and surprised some by holding off on a "Surface Mini". While Microsoft continued to harp on their "best of both worlds" mantra, it was very clear that this device was focused on productivity use cases and enterprise users. Does this signal a new era in tablet computing or is this simply a niche product?

I recently downgraded my tablet sales estimate because tablets haven't encroached upon productivity use cases as quickly as "phablets" have encroached on consumption use cases. So wouldn't the Surface Pro 3 fit with my definition of upmarket movement? Not quite. The challenge for tablets is to move upmarket into productivity use cases without compromising on their advantages over PCs -- 1) ease of use, and 2) lower price points. With the Windows 8 operating system and a price tag starting at $930 (incl. the keyboard cover), the Surface Pro 3 misses on both points.

The primary selling point of the Surface is access to legacy applications which are practically unusable without the keyboard cover (the fact that this is still sold as an optional accessory is puzzling). In other words, the Surface is not a tablet, but an ultraportable PC or "ultrabook" which happens to have a touchscreen. The product has been designed to cater to a very niche segment of enterprise users, i.e. users who have already decided to purchase a portable PC over a tablet. This leaves no room to move upmarket and no flexibility to move downmarket. The sub-par mobile app ecosystem for Windows Phone/RT limits downmarket movement as well.

That said, focusing on enterprise PC users may be a conscious decision by Microsoft. The lack of a "Surface Mini" announcement tells me that Microsoft is beginning to understand their position in the mobile industry. This strategy is unlikely to be a major success, but could drive just enough sales to keep the product line alive.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

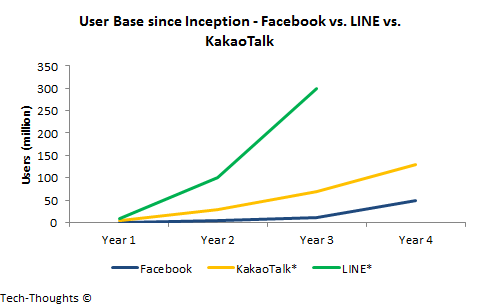

Unfair comparisons: Google and Facebook vs. messaging apps

Publié: avril 21, 2014, 6:24pm CEST par Sameer Singh

This weekend, I came across an interesting post by Benedict Evans on "unfair but relevant" comparisons. While I agreed with everything he said, his focus was entirely on the hardware side of the equation. It may be just as relevant to compare today's hot mobile services to online service start-ups from the PC era.

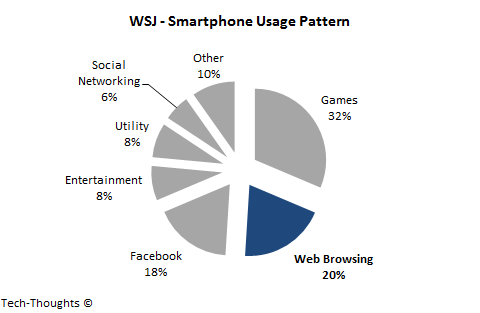

The chart above compares the growth of Facebook's user base, since inception, to that of KakaoTalk and LINE. One disadvantage here is that we can only compare registered users for messaging apps to active users for Facebook. According to one estimate, 61 percent of LINE's registered users are active. If this proves roughly accurate for major messaging apps, KakaoTalk and LINE would still overshadow Facebook's user growth by a considerable margin. This is because PC-era start-ups like Facebook and Google operated in a much smaller playground as compared to today's mobile start-ups. But the "scale of mobile" has already been beaten to death. Does that necessarily mean that these companies also make more money?

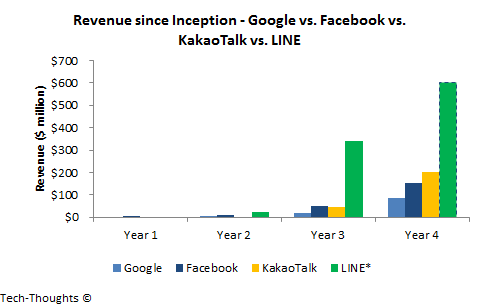

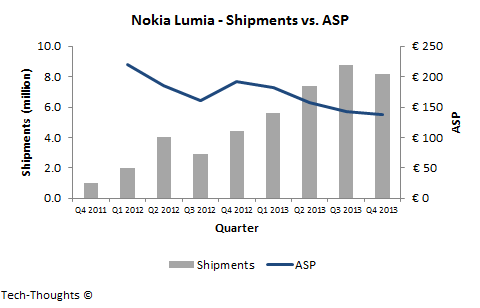

Now this is interesting. The chart above compares the revenue figures for Google, Facebook, KakaoTalk and LINE over their first four years of operation, starting from 1998, 2004, 2010 and 2011 respectively. Revenue figures for Google and Facebook have been sourced from their respective IPO prospectuses, while those for LINE and KakaoTalk are from company press releases. For LINE, I've taken a conservative estimate for Year four (2014) revenues by assuming average quarterly revenues of $150 million, 25 percent higher than its Q4 2013 revenue. In comparison, LINE's average quarterly revenue in 2013 was roughly 300 percent higher than its Q4 2012 revenue. All revenue figures for KakaoTalk and LINE are net of payments to developers and partners.

Over their first four years of operation, KakaoTalk and LINE have outpaced the revenue generated by both Google and Facebook. This is especially significant given that KakaoTalk is still considered a regional player. LINE, while smaller than Whatsapp, is more diversified geographically and dwarfs Google's and Facebook's early revenue performance. As it turns out, the playground isn't just larger, it's also better.

This story was reposted with permission from tech-thoughts.

Photo Credit: Violet Kaipa / Shutterstock

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of tech-thoughts.net. -

Amazon Fire TV: Business model motivations

Publié: avril 3, 2014, 4:40pm CEST par Sameer Singh

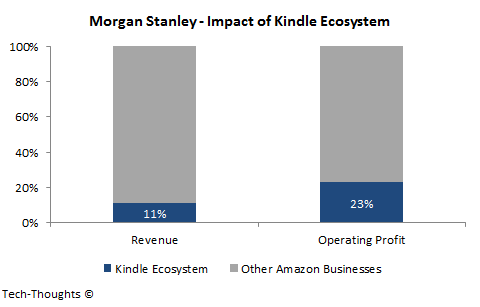

23 percent -- That figure alone explains Amazon's goal for Fire TV. In 2013, it was estimated that the Kindle ecosystem was responsible for 11 percent of Amazon's revenue, but 23 percent of its operating profit. However, the revenue numbers also include $4.5 billion in Kindle device sales (6 percent of Amazon's revenue) which were sold at breakeven. This means that 23 percent of Amazon's operating profit came from a business that accounted for just 5 percent of its annual revenue.