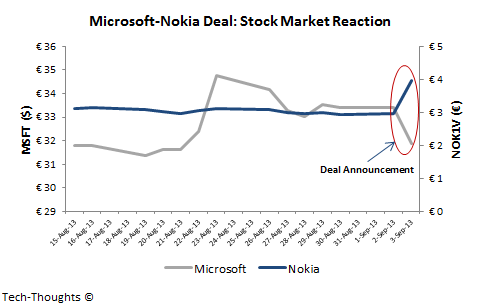

After Microsoft announced that it was acquiring substantially all of Nokia's devices & services business, the stock market painted a fairly accurate picture of what this deal means -- Nokia investors were relieved as the stock surged by nearly 35 percent, while Microsoft investors responded by driving the stock down by 5 percent. Based on my prior experience in technology M&A (Mergers and Acquisitions), I wanted to take a look at the motivations for the transaction and the viability of Microsoft's long-term consumer strategy.

Let's begin by taking a look at the deal terms. Microsoft will be paying Nokia €3.79 billion for its handset division (including 8,500 design patents) and another €1.65 billion in patent licensing. As a part of the deal, Microsoft will gain rights to the Lumia and Asha brands, but Nokia will retain the rights to the "Nokia" brand. However, Microsoft has licensed the "Nokia" brand, exclusively for use on low-end S30/40 feature phones.

Financial Perspective: Sell or Die Out

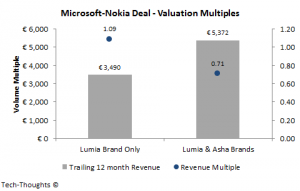

Nokia's "Devices & Services" division generated revenues of almost €27 billion over the last 12 months. However, this included Nokia's feature phone division which is practically worthless from Microsoft's perspective. At best, Microsoft may have considered the Asha range to be relevant, while ignoring the rest of the feature phone portfolio. Using Lumia revenues for the last 12 months, the deal was valued at 1.09 times revenue (effectively €187 for every Lumia sold in the past 12 months). If we use Lumia/Asha revenue, the deal was valued at 0.71 times revenue. Earnings multiples in this case were irrelevant as Nokia was making operating losses.

Nokia's "Devices & Services" division generated revenues of almost €27 billion over the last 12 months. However, this included Nokia's feature phone division which is practically worthless from Microsoft's perspective. At best, Microsoft may have considered the Asha range to be relevant, while ignoring the rest of the feature phone portfolio. Using Lumia revenues for the last 12 months, the deal was valued at 1.09 times revenue (effectively €187 for every Lumia sold in the past 12 months). If we use Lumia/Asha revenue, the deal was valued at 0.71 times revenue. Earnings multiples in this case were irrelevant as Nokia was making operating losses.

This seems like a very low valuation (about half of Xiaomi's), and yet Nokia investors seemed relieved. This is because Nokia could not have a received a comparable valuation from other potential buyers. Any other company would have had to take into account the financial impact of ending the Microsoft deal and moving to an alternate operating system.

But couldn't Nokia have held out for a higher valuation? Microsoft announced that it was providing Nokia with €1.5 billion in "unconditional" financing, which means that Nokia was in significant financial distress. If it couldn't reach a deal with Microsoft, it would have to sell to another company at a far lower valuation or consider bankruptcy. With this deal, Nokia's financial position seems secure.

Strategic Perspective: Microsoft's Desperation

Ever since Stephen Elop decided to tie Nokia's smartphone future to the Windows Phone OS, the company has been Microsoft's biggest and only relevant smartphone partner. However, over the last few quarters, it was becoming clear that the partnership had failed to deliver the financial results necessary to keep Nokia going. Any other move by Nokia would have essentially killed Windows Phone. Therefore, I have to conclude that this deal was born out of desperation, not just for Nokia, but for Microsoft as well.

But why did Microsoft need to acquire Nokia's feature phone business? My guess is that Nokia's board insisted on selling the smartphone and feature phone units together. In any other case, it would have been practically impossible for Nokia to find a buyer for a standalone, loss-making and rapidly shrinking feature phone business.

What Does Microsoft Plans To Do With Nokia?

Microsoft stated that it expected $600 million in cost synergies from the deal, which will probably come from scaling down Nokia's feature phone division. Interestingly, it also stated that the Asha brand would serve as the "on-ramp" for Windows Phone, i.e., corporate-speak for "we still don't have a low-end smartphone strategy". Based on this, I would have to think that Microsoft has seriously underestimated just how significant Nokia's remnant brand value was in driving smartphone sales, especially at lower price points. If Nokia, using its own brand, was unsuccessful in transitioning its feature phone customers to smartphone buyers, how would Microsoft accomplish this feat without a coherent brand?

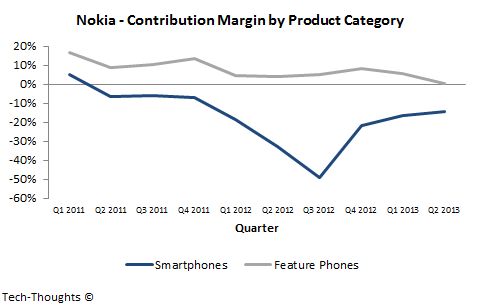

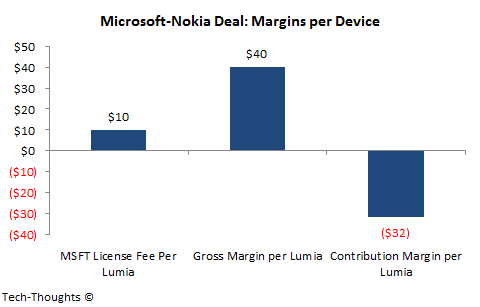

In a presentation outlining its rationale for the transaction, Microsoft stated annual Lumia sales needed to cross 50 million units to reach operating profitability. The problem is that this calculation assumes flat operating expenses. The contribution margin on Nokia's Smart Devices unit has been stubbornly negative, with gains coming exclusively from cost cuts.

Therefore, in order to increase Lumia volumes, Microsoft would need to cut prices and boost promotional expenses, pushing contribution margin deeper into the red. This leaves Microsoft without a financially viable hardware strategy. While Microsoft could continue throwing money at the problem, it doesn't make sense to continue to do so unless it has an alternative business model in place.

Microsoft's Devices and Services Business Model

The rapid destruction of Microsoft's PC-focused software business has forced the company to pivot to a "devices and services" strategy. The problem is, Microsoft still has not figured out a way to monetize services in the consumer segment -- its online services division still makes annual operating losses in excess of $1 billion. The entertainment business (Xbox) is modestly profitable, but a transition to mobile will not be easy. This essentially leaves hardware, which is rapidly being commoditized by modular competition, in addition to the Nokia-specific problems I highlighted above. Hardware margins are already being pressured and the situation is likely to be far worse by the time Microsoft completes its reorganization. Even if the reorganization is successful, it seems as though Microsoft is transforming itself into a vertically integrated hardware player at the worst possible moment.

With all these problems and facing the challenge of integrating Nokia into its "expanded devices and services unit" in the midst of a company-wide reorganization, I really don't see how this deal can be successful. Microsoft's track record with acquisitions certainly isn't an encouraging sign.

Reprinted with permission from Tech-Thoughts

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of Tech-Thoughts.

Sameer Singh is an M&A professional and business strategy consultant focusing on the mobile technology sector. He is founder and editor of Tech-Thoughts.