Emergency surgery is the appropriate analogy for the firing of the iconic CEO. Yes firing. Microsoft announced Steve Ballmer's departure today, quite unexpectedly, and in his own words "within the next 12 months, after a successor is chosen". Meaning: Soon as there is a replacement, he is gone. Vamoose. Adios. We'll send Christmas cards. Not!

Unless Ballmer is in ill-health, or something bad happened to someone he loves, he wouldn't just walk away whistling to the wind. The man is too passionate about Microsoft. There is but one interpretation: The board of directors gave Ballmer his pink slip.

Another telling sign: Ballmer couldn't leave at a worse time. The company is early days transition to "devices and services", and major restructuring is barely six weeks old. Meanwhile, smartphones and tablets suck the lifeblood out of the PC market, and Microsoft has little to no presence in these two disruptive categories. Executive transitions take time, which means steps backward before running forward again and disruption into devices and services categories that are the future. Timing hints at desperation somewhere in Microsoft's higher echelons.

Ballmer will leave Microsoft with checkered legacy and be blamed for every problem there will be over the next 24 months or so and every one there ever was. Microsoft shares closed up more than 7 percent on news of his exit. That's just the beginning. Ballmer will burn in effigy for months. Analyses will flood the InterWebs picking apart his legacy like vultures on a carcass.

That's his new role. Fall guy. Scapegoat. For the sake of the company he loves, Ballmer will suck it up and take the beatings, which will be vicious and venomous. But in many ways they are undeserved.

No Thanks to Gates

Nearly four years ago, I detailed the company's problems in post "2000-2009: Microsoft's decade of shattered dreams". Three years ago: "Five reasons why Microsoft can't compete (and Steve Ballmer isn't one of them)". The content of both posts is hugely relevant context for understanding how the chief executive comes to such pitiful end. That these years-old posts are so relevant now is commentary on just how little has changed -- how long the patient suffered sickness.

Among those five reasons: "U.S. and European antitrust cases put lawyers and non-technologists in charge of important final product decisions"; "Microsoft lost control of file formats". Both are connected, but the other three reasons still apply.

Cofounder Bill Gates handed Ballmer a mess in January 2000, when he stepped aside and his buddy became chief executive. U.S. District Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson had issued preliminary findings against Microsoft in its U.S. antitrust case. Those would become final three months later, followed by an order to break up the company into two separate entities. Microsoft escaped this outcome by settling with federal and state attorneys general in November 2001, a month after Windows XP shipped. The company immediately began complying with the consent degree even though another year passed before being approved by Jackson's successor.

Government oversight brought tremendous burden, which weight increased following another adverse antitrust ruling from the European Union, in 2004. Integration and cross-tying features among products and services was one of Gates' two legacies. The other is controlling file formats. Government oversight compelled Microsoft to be less aggressive. The company cautiously advanced or passed on new technologies that made sense going into Windows or closely tied to it.

For example, Microsoft released anti-malware software during the mid-Noughties but separately from Windows (and with antivirus vendors crying unfair competition about integration). The company should have incorporated an app store into the flagship operating system long before Windows 8 -- at least when competitors did. Surely, Microsoft product managers and lawyers asked about everything related to Windows: "What if?" "What if we integrate this into Windows? Or that?"

Anti-malware and app store integration only came to Windows after U.S. government oversight ended in May 2011; not coincidentally, hints of the old, aggressive Microsoft re-emerged and cross-integration resumed anew for Windows (it never stopped for Office). But too late. By backing away from an integration philosophy fundamental to Microsoft's success, Windows became a much less appealing product for consumers or platform for developers. Competitors successfully advanced new platforms beret of Microsoft's monopoly; they succeeded so well, the PC nears extinction.

Last Stand: Customers First

Meanwhile, Microsoft lost control of file formats, which had propelled both Office and Windows to dominance. Antitrust oversight is one reason. Ballmer's management style is another. Gates' aggressive, competitive character led Microsoft from startup to giant. But by the late 1990s, the company had become victim of its own success. Core markets saturated, with newer Office and Windows versions competing with the old ones. Microsoft increasingly sold to the same customers, mostly large businesses, which decreasingly upgraded. Because: What they had often was good enough, and IT-organizations are by character risk-adverse.

Given such circumstance, Ballmer appeared to be the right choice for CEO in 2000. He is a sales guy, someone who speaks customers' language and understands their needs. Gates' aggressive tactics worked for a growth company, but not a mature one looking to preserve existing revenue streams.

Under the new leadership, Microsoft put more emphasis on satisfying customers and opening new spigots to get cash from them, starting with changes to volume licensing in 2001 and 2002. Microsoft also acquiesced to enterprise demands for more interoperability, thus ceding control of long-held file formats and related, adopted standards.

Steve Ballmer's emphasis on customers shouldn't be a liability, but it is for Microsoft. Customers-first also means catering to their needs. But innovation isn't about listening to what customers want, but giving them something they don't realize they need. This is the fundamental difference between how Apple and Microsoft develop new products. Microsoft caters to enterprises and their fickle and risk-adverse behavior. Apple ignores everyone.

Then there are shareholders to consider. Microsoft made bundles of money selling to an entrenched customer base, something Ballmer and senior leaders chose not to disrupt by wildly venturing into new categories. As such, priorities like making new products backward-compatible with old ones acted like anchors on a ship. Microsoft couldn't move forward, certainly not fast enough.

The Legacy

In that regard, the company is like IBM during the early PC era. Big Blue chose preserving mainframe customers and the oodles of revenue they generated rather than aggressively embrace the personal computer. The PC could have saved IBM, which early models were the categories' standard bearers, but instead buried the mainframe giant.

Microsoft missed opportunities that competitors achieved. The first tablets running Windows went on sale in 2002, while Windows Mobile was the up-and-comer on smartphones in 2005 and 2006. Not until Apple got the user interfaces right, with emphasis on touch, did smartphone and tablet sales explode, blowing a hole in the monopoly-fortress protecting Windows and allowing competing platforms Android and iOS to rush in. Microsoft couldn't move fast enough because of those anchors.

The Ballmer-legacy bone pickers will use past statements about products like iPhone as evidence he is a clueless leader who just doesn't get it. That he lives in denial. But Microsoft's CEO has other priorities, whether right or wrong: Protecting the amassed customer base for Office and Windows, which delivered, even during fiscal 2013, 78 percent of profits generated by four of the five divisions (I exclude Online Services, which lost more than $8 billion).

One of my favorite film scenes is in "Sum of All Fears". The new Russian president takes the blame for an unprovoked chemical weapons attack on Chechnya, which he didn't order. He tells a subordinate: "These days, better to appear guilty than impotent". The point: Ballmer chose bravado and to project confidence when dismissing products like iPhone and iPad, which he did quite colorfully. Saying these devices won't amount to much doesn't mean that's what he believes.

Ballmer actually has demonstrated amazing cunning recognizing his adversaries, just not the best execution dealing with them. For example, he started warning about Google as a competitor about a decade ago, when the company's only business was search. Now Google is gatekeeper to the Internet, assuming a role government trustbusters accused Microsoft of taking in the late-1990s. For months I've toyed with writing a story with the headline "Steve Ballmer was right, I was wrong" about the Google threat. Perhaps I will still. I was among those dismissing the search and information giant as Microsoft competitor during the last decade. Ballmer had foresight. I did not.

The New IBM

Microsoft stands today where IBM did in 1993 -- at the far cusp of changing computing eras. The mainframe gave way to the PC, which in 2013 hands-off to cloud-connected devices. The new era is contextual cloud computing, where anytime, anywhere access is more important than the connecting device.

IBM survived by bringing in outsider Lou Gerstner, and he saved the company by transforming it around core values steeped in customer service and integration. Microsoft's board must decide whether an outsider could achieve something similar. Everyone acts like the PC is already dead. No! The PC's role changes, from being the hub connecting devices and information to one among many connected to the cloud hub.

Cloud-connected devices buried Ballmer, but they don't have to be Microsoft's end. Radical leadership is necessary now, and I'm convinced only an outsider can bring it. Like IBM and Gerstner, the cure will be painful and take years, and Microsoft might have to lose major battlegrounds smartphones and tablets along the way.

There's irony in a way about the timing of Ballmer's forced-retirement announcement. Hell, it is almost spiteful. Today, Googorola started selling Moto X, which is the metaphor for where computing is going and marks how far Microsoft is behind. The Google/Motorola smartphone should be the tech news of the day, but Microsoft steals away thunder.

The original iPhone is a stunning achievement in the annals of technology, mainly because of its responsive, human-like qualities. The device fundamentally changed the paradigm, making the touchscreen the primary user interface. But the future is Star-Trek like voice interaction, which is core to the new Motorola phone.

Touchless interaction is the most disruptive change in computing and consumer electronics since the original iPhone popularized touch. Touchless interaction will be integral to future tech designs, everything from phones to cars to refrigerators -- like asking for the day’s weather when getting milk for the morning coffee. I explain more here.

Microsoft could have gotten there first. The company bought Tellme in early 2007 and has Windows Phone, Bing search, maps and other services that mirror those Googorola uses for Moto X's voice command and responsive features. Ballmer assembled the pieces but couldn't put them together. Perhaps his successor will do better.

I honestly expected Ballmer to survive longer, despite calls for his head. I'm sorry to see him go. To the people so long waiting for this day, be careful for what you wish.

So Steve Ballmer is leaving Microsoft a year from now: what kind of schedule is that? It’s one thing, I suppose, for a company to point out that it has a retirement policy or a succession plan, or even to just give the universe of potential Microsoft CEOs a heads-up that the job is coming open, but I don’t think that’s what this is about at all. It’s about the stock.

So Steve Ballmer is leaving Microsoft a year from now: what kind of schedule is that? It’s one thing, I suppose, for a company to point out that it has a retirement policy or a succession plan, or even to just give the universe of potential Microsoft CEOs a heads-up that the job is coming open, but I don’t think that’s what this is about at all. It’s about the stock.

First released back in 2006,

First released back in 2006,  A month ago my colleague Brian Fagioli complained that

A month ago my colleague Brian Fagioli complained that  The man behind UK cloud and hosting provider

The man behind UK cloud and hosting provider  I can't get these words out of my head. I've been repeating them over and over. No, I am not going crazy (I hope), I have been using Motorola's newest flagship Android device, the Moto X -- "OK Google Now". This device focuses heavily on voice interaction -- particularly with those words that have found a home in my brain.

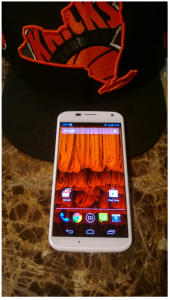

I can't get these words out of my head. I've been repeating them over and over. No, I am not going crazy (I hope), I have been using Motorola's newest flagship Android device, the Moto X -- "OK Google Now". This device focuses heavily on voice interaction -- particularly with those words that have found a home in my brain. Upon taking the device out of the small box, I was immediately taken aback by the good-looks of the device -- it is art. My particular Moto X, on AT&T Wireless, is all white. However, AT&T customers can opt for a customized color palette for the smartphone by using Motorola's Moto Maker. While I think this color customization will prove popular with some, an all-white smartphone is classy and mature.

Upon taking the device out of the small box, I was immediately taken aback by the good-looks of the device -- it is art. My particular Moto X, on AT&T Wireless, is all white. However, AT&T customers can opt for a customized color palette for the smartphone by using Motorola's Moto Maker. While I think this color customization will prove popular with some, an all-white smartphone is classy and mature. Pandora, the popular music service, is adding yet another feature to its mobile app. The customizable radio station service, built on the Music Genome project, splits its time between development and fighting for its right to be treated as a radio station in the eyes of the MPAA.

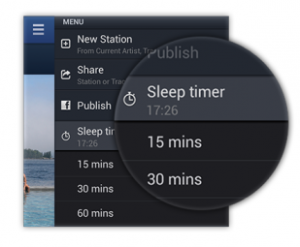

Pandora, the popular music service, is adding yet another feature to its mobile app. The customizable radio station service, built on the Music Genome project, splits its time between development and fighting for its right to be treated as a radio station in the eyes of the MPAA. Building your family tree on a website like Ancestry.com has plenty of advantages. You'll get easy access to a host of records; you can use these to locate and add missing family members in just a few clicks, and it’s simple to share your work with anyone else who might be interested.

Building your family tree on a website like Ancestry.com has plenty of advantages. You'll get easy access to a host of records; you can use these to locate and add missing family members in just a few clicks, and it’s simple to share your work with anyone else who might be interested.