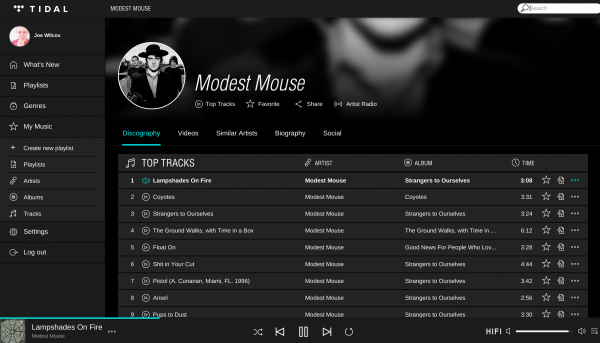

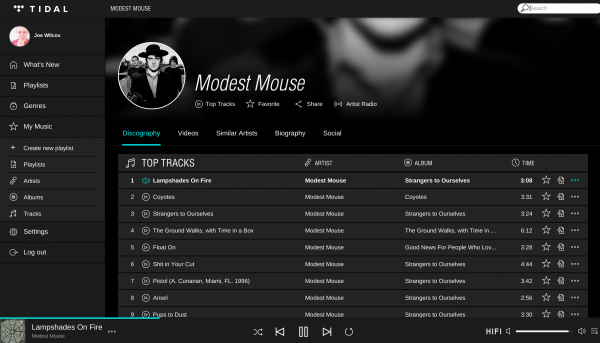

Fraking fantastic is my reaction to Tidal's high-definition audio. I spent much of April Fools' Day testing, and quite enjoying, the music service, although I am skeptical that most streaming subsctibers will care—not for $19.95 per month. Still, I see hope for the 10-buck standard quality other option if Tidal delivers enough artist exclusives and superior curation. The iTunes hegemony, and Apple's rapidly evolving Beats Music acquisition, is all about content, much of it available nowhere else, better presented, and more easily discovered. With musicians' support, and unique content with it, maybe, just maybe, a Tidal wave approaches.

The service essentially relaunched on March 31, 2015, with a gala event hosted by Jay-Z and other music superstars. He acquired Tidal, for $56 million two months earlier, but the lossless streaming service launched in October 2014. Architecture, audio quality, two-tier pricing, and streaming are essentially unchanged. New owners' commitment, that of other artists, big marketing push, and 30-day trial distinguish Tidal today.

My month free started April 1, and as the days tick down to zero I will assess the value of real CD-quality music. Let's identify what that term means, because definitions are important. Music stores or services claiming CD-quality usually deliver bitrate of 320kbps. They lie about what that is. The compressed files aren't even close to the original. Using the Free Lossless Audio Codec, Tidal promises the real thing: 44 kHz, 16bit, and 1411kbps bitrate. Is that better enough for the price, when free too often sets standard pricing? I wonder, and so should you.

Details, Details

I hear the difference immediately. Detail is finer, overall ambiance is brighter (e.g. less muddy), vocals are crisper but also flatter, and bass is more natural rather than pounding. I tested on Chromebook Pixel LS with Harmon Kardon SoundSticks II and on Nexus 6 with Grado Labs RS1e headphones. Whether or not lossless is better depends much on the equipment used. Better the audio processor and attached speakers or headphones, the more likely listeners will discern differences from 320kbps MP3s or, from Apple, 256kbps AAC.

In my initial Pixel testing last month, I found bass to be heavier than the 2013 model, streaming Google Music. But Tidal remedies that problem, and I am surprised by it. While music of all types sounds clear with the setup, the differences may be too subtle for most people. Both services stream through the web browser.

Headphones are another matter, depending on what they are. In my Nexus 6 review, I praised the Grados combination, which delivers great ambiance and soundstage streaming Google Music. Tidal is noticeably better. My ears delight, but I am undecided about which to prefer. Perhaps I am too spoiled from listening to heavily-compressed, lower-bitrate music for so long. My CD listening days ended more than a decade ago. I traded fidelity for convenience after Apple opened iTunes Music Store in Spring 2003.

My 20 year-old daughter grew up with the iTunes sound—compressed, muddy, bassy, and loud. I spent my youth and radio DJ days listening to vinyl. When trying out my Grados on typically compressed music, she complains about how awful it sounds, whereas the fine detail the cans reveal is exquisite to my ears. Tidal's lossless tracks are even better. For this initial test, I only used high-end headphones. For fuller review, I will try others.

Compression Tactics

Preference (e.g. what you're used to) is a potential problem for Tidal's success wooing subscribers to higher-cost high-def, and it relates to another: How music is engineered, and whether, say, dynamic range is the same for HiFi tracks as those more heavily compressed. At this early stage of testing and reporting I can't answer for Tidal tracks. I will ask the company and experts for my complete review.

Further explanation is necessary. Because of the aforementioned changing listening preferences and logistical limitations inherit to heavily-compressed files, much of the fidelity is lost. An excerpt from a September 2007 Wall Street Journal news analysis so aptly, and disturbingly, describes the changes that I clipped and saved it:

Contemporary pop music has a characteristic sound, says veteran L.A. engineer Jack Joseph Puig, whose credits include the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton. 'Ten years ago, music was warmer; it was rich and thick, with more tones and more real power. But newer records are more brittle and bright. They have what I call implied power. It's all done with delays and reverbs and compression to fool your brain'.

When first listening to the Tidal stream—Modest Mouse tune "Lampshades on Fire" from Chromebook Pixel LS—my first reaction: "It's not as loud" but fuller and, as previously stated, not as bassy.

Two months after seeing the Journal story, another, dateline Dec. 27, 2007, in Rolling Stone, depressed me. I read the story in print more than 7 years ago, and wasted nearly two hours yesterday trying to: find it in the RS archive, understand why it's not there, and locate a legitimate copy to link to. Fail on all accounts, but frak it, I link anyway.

Two months after seeing the Journal story, another, dateline Dec. 27, 2007, in Rolling Stone, depressed me. I read the story in print more than 7 years ago, and wasted nearly two hours yesterday trying to: find it in the RS archive, understand why it's not there, and locate a legitimate copy to link to. Fail on all accounts, but frak it, I link anyway.

"The Death of High Fidelity: In the age of MP3s, sound quality is worse than ever", by Robert Levine, is riveting reading. He writes that "a revolution in recording technology has changed the way albums are produced, mixed and mastered—almost always for the worse". Music is louder, for example. "Engineers do that by applying dynamic range compression, which reduces the difference between the loudest and softest sounds in a song". By contrast, "wide dynamic range creates a sense of spaciousness and makes it easier to pick out individual instruments".

Tidal's lossless music most certainly sounds fuller, more spacious, to my aging ears, whether streamed or listened to on the device. The company's explanation video is pretty good demonstrating the differences. I hear them. Do you? Are they enough that you would spend $20 a month instead of $10?

One reason I long recalled the Rolling Stone story is this statement: "Many remastered recordings suffer the same problem as engineers apply compression to bring them into line with modern tastes". The process evens out the volume between the different instruments, which is unnatural and changes—I say destroys—soundstage. The point: Remastered doesn't mean better, but can be worse.

If you're not tired reading all this technical stuff, the Economist audio compression primer is informative, too.

My hope: If lossless catches on with listeners, or even just the artists, music engineering will break a way from more than a decade of compression tactics that take away something and return to giving listeners the fuller studio recording experience.

Do Differences Matter?

That's good segue to discuss lossless listening from the Android app, which I installed yesterday, and the value of the two subscription tiers. For people who can't hear the difference between 320kbps compressed and FLAC, the $9.99 option is comparable to all the major paid services.

Harping again about the differences, you can test for yourself during the 30-day trial, as I started April 1. I listened to several favorite songs, first on Tidal, then Google Music, and back to Tidal. I then switched among the three different Tidal Sound Quality choices and listened to the same song using each. High-def lossness' fullness and details are clear to my aging ears, whether compared to Google Music or Tidal's own heavily compressed options. While subtleties are many, particularly higher tones, you may not care, if bass-thumping, DJ-remixed electronic is your preferred genre.

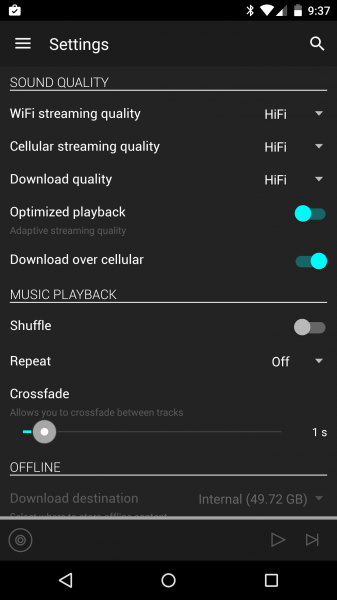

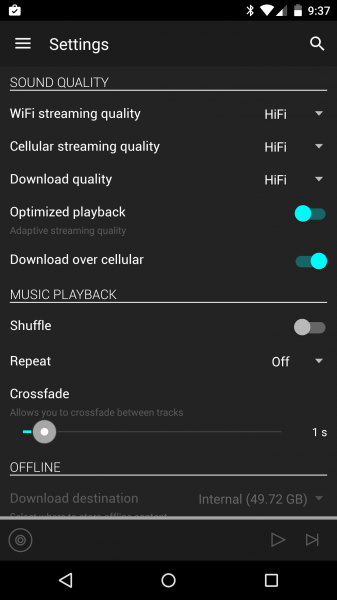

Oh, before doing anything with Tidal, you will want to go into Settings in your mobile app. The defaults are optimized for data conservation. Sound Quality default is "Normal", not "HiFi", for cellular and WiFi streaming and downloads—for the latter you will need to authorize the device. Be mindful if listening locally, with no Internet connection.The lossless Modest Mouse album I downloaded took up 525MB of storage.

The Android app is fabulous. I can't say enough good about it, after just a few hours use. The interface is super smooth and clean running on my Nexus 6. Even better: The Tidal app works well with my Moto 360—so, like Google Music, I see what's playing on the smartwatch, where songs can be paused, skipped, or rewound, too. I presume, and will see later this month, that Apple Watch owners will have same capability connected to iOS devices.

Music discovery is better on the Android app than from the web browser, but not nearly as good as Beats Music, iTunes, or even Google Music. For a service that should, at the least, appeal to audiophiles, featured artists and playlists too much emphasize the majors, radio-play popular, and Tidal musician supporters.

Music discovery is better on the Android app than from the web browser, but not nearly as good as Beats Music, iTunes, or even Google Music. For a service that should, at the least, appeal to audiophiles, featured artists and playlists too much emphasize the majors, radio-play popular, and Tidal musician supporters.

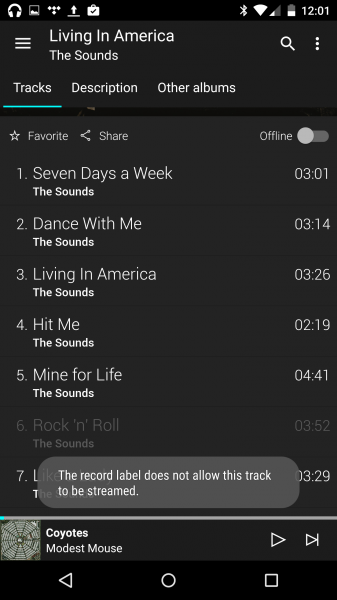

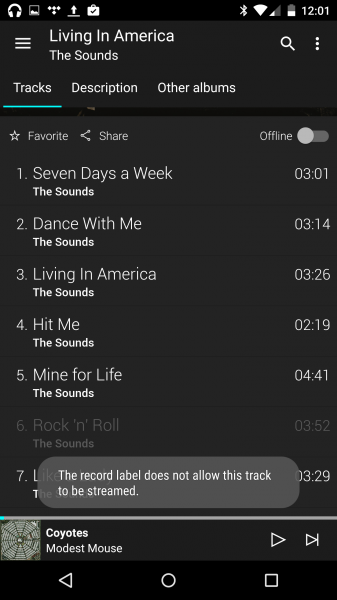

The service claims a 25-million track library. Selection is excellent but also deficient. In fairness, some of my artist searches are unfair for the target audience. That started because a track I often use when testing music services is missing: The Sounds' "Rock `N Roll". Every other song from the Living in America album is there, like on iTunes or Google Music. So I searched for obscurity—1970s Dutch band Kayak, which even Google Music streams. Goose egg on Tidal. Later the same decade: Nick Lowe. While good, his Tidal collection misses the one important album, Jesus of Cool (released as Pure Pop for Now People here in the United states).

For more popular artists, Tidal satisfies—and if you want to stream some of them, notably Taylor Swift, there is no other option (of course, you can always buy at other digital music stores, like iTunes). Nice touch: Shazam-like audio search is built-in to the app. If something is playing, say, over the clothing store speakers, Tidal likely can identify it.

I will have more to say about the app, Tidal curated content, sharing, playlists, high-definition videos, and more in my full review. By the way, I am skeptical about the videos' value when YouTube offers so much. We shall see.

Wrapping up, I had mega deja vu while trying out Tidal yesterday. The aural quality shook cobwebs from my brain, and ushered up feelings from listening to music before iTunes—from CDs and vinyl.

Illustration Credit: Regissercom/Shutterstock