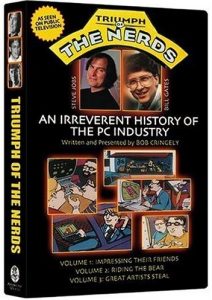

Third in a series. Editor: In parts 1 and 2 of this serialization, Robert X. Cringely presents an updated intro to his landmark rise-of-Silicon Valley book Accidental Empires. Here he presents the original preface from the first edition.

Third in a series. Editor: In parts 1 and 2 of this serialization, Robert X. Cringely presents an updated intro to his landmark rise-of-Silicon Valley book Accidental Empires. Here he presents the original preface from the first edition.

The woman of my dreams once landed a job as the girls’ English teacher at the Hebrew Institute of Santa Clara. Despite the fact that it was a very small operation, her students (about eight of them) decided to produce a school newspaper, which they generally filled with gossipy stories about each other. The premiere issue was printed on good stock with lots of extra copies for grandparents and for interested bystanders like me.

The girls read the stories about each other, then read the stories about each other to each other, pretending that they’d never heard the stories before, much less written them. My cats do something like that, too, I’ve noticed, when they hide a rubber band under the edge of the rug and then allow themselves to discover it a moment later. The newspaper was a tremendous success until mid-morning, when the principal, Rabbi Porter, finally got around to reading his copy. "Where", he asked, "are the morals? None of these stories have morals!"

I’ve just gone through this book you are about to read, and danged if I can’t find a moral in there either. Just more proof, I guess, of my own lack of morality.

There are lots of people who aren’t going to like this book, whether they are into morals or not. I figure there are three distinct groups of people who’ll hate this thing.

Hate group number one consists of most of the people who are mentioned in the book.

Hate group number two consists of all the people who aren’t mentioned in the book and are pissed at not being able to join hate group number one.

Hate group number three doesn’t give a damn about the other two hate groups and will just hate the book because somewhere I write that object-oriented programming was invented in Norway in 1967, when they know it was invented in Bergen, Norway, on a rainy afternoon in late 1966. I never have been able to please these folks, who are mainly programmers and engineers, but I take some consolation in knowing that there are only a couple hundred thousand of them.

My guess is that most people won’t hate this book, but if they do, I can take it. That’s my job.

Even a flawed book like this one takes the cooperation of a lot of really flawed people. More than 200 of these people are personal computer industry veterans who talked to me on, off, or near the record, sometimes risking their jobs to do so. I am especially grateful to the brave souls who allowed me to use their names.

The delightfully flawed reporters of InfoWorld, who do most of my work for me, continued to pull that duty for this book, too, especially Laurie Flynn, Ed Foster, Stuart Johnston, Alice LaPlante, and Ed Scannell.

A stream of InfoWorld editors and publishers came and went during the time it took me to research and write the book. That they allowed me to do it in the first place is a miracle I attribute to Jonathan Sacks.

Ella Wolfe, who used to work for Stalin and knows a lost cause when she sees one, faithfully kept my mailbox overflowing with helpful clippings from the New York Times.

Paulina Borsook read the early drafts, offering constructive criticism and even more constructive assurance that, yes, there was a book in there someplace. Maybe.

William Patrick of Addison-Wesley believed in the book even when he didn’t believe in the words I happened to be writing. If the book has value, it is probably due to his patience and guidance.

For inspiration and understanding, I was never let down by Pammy, the woman of my dreams.

Finally, any errors in the text are mine. I’m sure you’ll find them.

Reprinted with permission

Perhaps it is just me, but Microsoft's decision to take Live Mesh off of life-support has hit especially hard. We

Perhaps it is just me, but Microsoft's decision to take Live Mesh off of life-support has hit especially hard. We

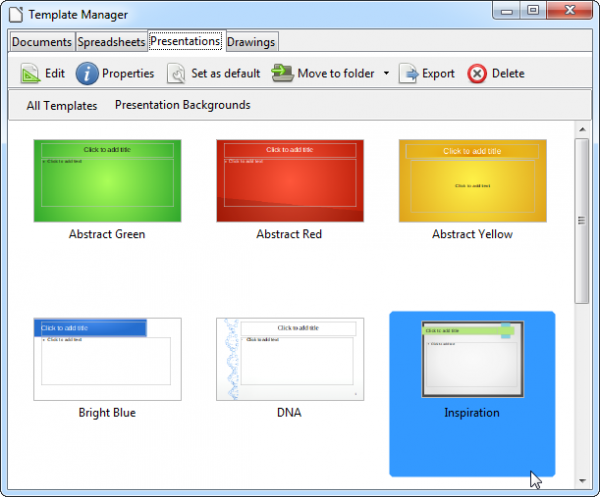

The Document Foundation released

The Document Foundation released

Microsoft's efforts to downplay Google's Gmail over its own Outlook.com service are well known amongst the tech crowd. In late-November the Redmond, Wash.-based corporation claimed that

Microsoft's efforts to downplay Google's Gmail over its own Outlook.com service are well known amongst the tech crowd. In late-November the Redmond, Wash.-based corporation claimed that  Take a photo with most digital cameras and by default you’ll get a JPG file, which is great for compatibility purposes, but does involve some compromises in image quality. And that’s because your picture will go through various processes before the final JPG is produced -- sharpening, adjusting colors and contrast, compressing the results -- and each step results in the loss of some information.

Take a photo with most digital cameras and by default you’ll get a JPG file, which is great for compatibility purposes, but does involve some compromises in image quality. And that’s because your picture will go through various processes before the final JPG is produced -- sharpening, adjusting colors and contrast, compressing the results -- and each step results in the loss of some information. Life gets more interesting when you click the Adjustments tab, though, where Scarab Darkroom provides tweaks for Exposure (Brightness, Contrast, Recovery, Blacks, Fill Light), Colors (Temperature, Tint, Hue, Saturation, Vibrance), Tone Curve (Highlights, Midtones, Shadows) and Sharpness. Drag a particular slider and the picture will update accordingly, giving you immediate feedback. And it’s easy to copy your settings to the clipboard, and restore them later, so once you’ve found a configuration which delivers good results then you can quickly apply it to all your other shots.

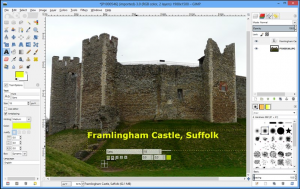

Life gets more interesting when you click the Adjustments tab, though, where Scarab Darkroom provides tweaks for Exposure (Brightness, Contrast, Recovery, Blacks, Fill Light), Colors (Temperature, Tint, Hue, Saturation, Vibrance), Tone Curve (Highlights, Midtones, Shadows) and Sharpness. Drag a particular slider and the picture will update accordingly, giving you immediate feedback. And it’s easy to copy your settings to the clipboard, and restore them later, so once you’ve found a configuration which delivers good results then you can quickly apply it to all your other shots. Popular open-source image editor

Popular open-source image editor  Platform-specific improvements concentrate on the OS X platform -- the gimpdir has been moved to the user’s Library\Application Support folder, while the system screenshot tool is now used when creating a new image from a screenshot. Plug-in windows should now automatically appear on top, and users can now select their chosen language via GIMP’s Preferences dialog.

Platform-specific improvements concentrate on the OS X platform -- the gimpdir has been moved to the user’s Library\Application Support folder, while the system screenshot tool is now used when creating a new image from a screenshot. Plug-in windows should now automatically appear on top, and users can now select their chosen language via GIMP’s Preferences dialog. According to Symantec, businesses are increasingly at risk of insider IP theft, with staff moving, sharing and exposing sensitive data on a daily basis and, worse still, taking confidential information with them when they change employers.

According to Symantec, businesses are increasingly at risk of insider IP theft, with staff moving, sharing and exposing sensitive data on a daily basis and, worse still, taking confidential information with them when they change employers. Three days ago evad3rs

Three days ago evad3rs  Second in a series. Editor: Robert X. Cringely is serializing his classic Accidental Empires , yesterday with a

Second in a series. Editor: Robert X. Cringely is serializing his classic Accidental Empires , yesterday with a