I’m a huge fan of Raspberry Pi, the super-affordable ARM GNU/Linux computer that’s bringing programming back into schools (and beyond). In one year alone, more than a million Pis have been sold globally, which is a phenomenal achievement, and demand for the uncased credit card-sized device shows no signs of abating.

I’m a huge fan of Raspberry Pi, the super-affordable ARM GNU/Linux computer that’s bringing programming back into schools (and beyond). In one year alone, more than a million Pis have been sold globally, which is a phenomenal achievement, and demand for the uncased credit card-sized device shows no signs of abating.

I chatted to Liz Upton, Head of Communications at Raspberry Pi Foundation (and wife of the foundation’s Executive Director Eben), about their eventful first year, and plans for the future.

BN: How did the idea of Raspberry Pi come about?

LU: Back in 2006, when Eben was teaching at the University of Cambridge he started to notice a decline in both the numbers of kids applying to read Computer Science, and in the level of knowledge that those kids arrived at the university with. We talked about it with our friends in the pub, like you do. And plenty of them thought it was a real problem too -- some of them thought it was such a problem that we came together and decided we'd try to do something about it. We had a hypothesis: that the fall in numbers and skills had to do with the disappearance of programmable machines in kids' lives. Computers like the BBC Micro or the Amiga had been replaced from the bottom end by sealed-unit, black-box consoles, whose whole business model is that you shouldn't be able to program them. And from the top, there was the PC. Of course, a PC is a wonderfully programmable machine; but in most families it's also a very vital tool for family life. It's where you do your banking or your homework. And many kids aren't allowed to mess around with the family PC for fear of breaking it. We felt a very cheap, programmable unit that kids could buy with their own pocket money, so they had a sense of ownership, was a possible solution. It's still early days, but on seeing some of the kids who've had a Pi for some months now, I've a feeling we were on to something.

BN: Where did the name come from?

LU: "Raspberry" comes from the tech industry's fondness for fruit names (there are lots of fruit-named computer companies, like Apricot, Tangerine…those, of course, are the only ones I can think of off the top of my head). And "Pi" is for Python, which has always been our first choice of teaching language (it was even before we knew what the hardware would look like). We initially thought that using Pi rather than Py would make for a really nice logo in the shape of the Greek letter, but as you can see, we didn't actually end up going that way!

BN: You’ve just sold your millionth Pi. Are you surprised by its success?

LU: Around the end of 2011, just before we started selling Pis, we started to worry that perhaps we'd bitten off more than we could chew. We'd managed to raise enough capital among ourselves to produce 20,000, and the plan was to use the profits from those Pis to seed the next batch (which would have taken a couple of months to make), and so on. We realized that we might have a problem on the day when we made a pre-released OS available for the Pi, well before anyone actually had one -- all of a sudden 60,000 people arrived on our website and downloaded this buggy software for a platform that didn't even exist yet. It suggested that the demand was much, much bigger than we'd anticipated. We decided that we'd need to revise the business model, because there was no way we could make enough fast enough with the resources we had to satisfy the sort of demand we were seeing. So we approached RS and Farnell, two British components companies which already had world-wide distribution networks in place, to see if they'd be interested in manufacturing the Pis for us under license so we could build up to a workable level of stock immediately. That was an enormous help in trying to deal with the demand we were seeing, but as you're probably aware, we've still been running to keep up, even though there is currently one Pi coming off the production line in Wales every few seconds!

BN: Raspberry Pi seems like a very British project, a modern day BBC Micro, but it's been well received in America. Why do you think that is?

LU: I think that a need for access to tools is universal. And those problems of introducing kids to programming -- the ubiquity of the family PC and the games console -- are universal too, at least in the developed world. Industry is starting to notice a decline in standards in young people too; we work with a number of industry bodies in the UK and in the US which are also promoting proper computing for young people, because they don't want to see a situation where the skills base dries up and blows away either. Eben and I will be at Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Phoenix in a couple of months, to do some work with the kids there. I love doing this stuff; and it's always so much fun in the US, with the American tradition of science fairs (which we don't have a real equivalent of in the UK).

BN: The Pi is manufactured in the UK. Why did you switch from China?

LU: Moving production to the UK was a purely pragmatic decision: the Sony factory in Pencoed, South Wales, was able to match the prices we were seeing in China because they use a lot of smart automation and lean practices. It's far more convenient for us; if there's a problem we can jump in the car and be there in a few hours, and there's no language or cultural barrier. And Sony really knows how to build a robust, quality product.

We really wanted to manufacture in the UK from the start, but none of the factories we spoke to when the Pi was under development (we weren't aware that Sony had a plant with the capacity to do this back then) were prepared to risk producing a machine for a company with no proven track record and a fuzzy idea of what sales might look like. So we did what so many small manufacturers do, and went to China, where factories were prepared to deal with what we thought at the time would be small volumes.

From a patriotic point of view, it's been absolutely wonderful to bring the Pi back home. Eben was born about ten miles away from the factory where the Pis are made, and we still have family out there, so we know the area pretty well. South Wales is one of those places which had a rich manufacturing heritage and used to be quite wealthy, but it's changed dramatically as the UK's manufacturing industry has declined. So we're really, really delighted to be able to bring some jobs back to the area, and to be able to demonstrate to people that yes, you can build in the UK for the same amount of money you'd be spending overseas. We'd love to see more electronics companies in this country do the same; it's great for the economy, and there's a real sense of pride in being able to write "Made in the UK" on your product.

BN: How did the Minecraft Pi edition come about?

LU: We think that a hook, something that isn't on-the-face-of-it educational, is vital if you're going to make something desirable to kids. After all, I learned to program when I was a kid because I had a BBC Micro, I played games on it, and I wanted to make my own. That's not an unusual trajectory. Minecraft's a fantastic tool to get kids interested in what they can do with the platform -- and for the Pi Edition, Mojang made sure that the game API would be hackable, so kids are encouraged to do a little programming in-game to make their Minecraft world swankier. We've seen some great stuff come out of that; kids are making analogue clocks in the Minecraft world, and great big 3D versions of games like Snake and Pacman.

BN: Any other similar tie in projects planned. An Elite: Dangerous version perhaps?

LU: I really ought to twist David's arm on that one! [David Braben, co-author of Elite is one of the Raspberry Pi Foundation’s trustees]

BN: What are some of your favorite Pi community projects?

LU: That's becoming an increasingly hard question to answer. There are so many projects out there that we find at least one thing every day that's impressive enough to make our blog. It's hard to beat the Beet Box for humor -- it's a project which uses a Pi and a Makey Makey to make a capacitive-touch drum kit out of root vegetables. There's loads of fun stuff like that. But if we're being serious, I've been most touched by some of the adaptive technology we've seen being made with the Pi; there was a guy who made a single-button audiobook machine for his elderly grandmother, who has very limited vision and mobility, and loves books. Hit the button once: your book starts. Hit it again: it stops. And when you get to the end, it automatically starts the next book. It's not difficult or terribly complicated technology, but it's made a huge difference to one lady's life.

BN: You've had an eventful first year. What have been some of the highlights for you?

LU: It's not the awards or the sales figures: the thing that really gets me is watching people's lives change because of this thing we're doing. Paul Beech, the guy who won the competition we ran to find a logo, is a great example: when we met him he was a freelance designer, but in the last year he's set up a company called Pimoroni, with a small factory and a bunch of employees to make Pi cases and other neat Pi stuff. They're great; they make a big effort in their local community in Sheffield to support making and hacking; and they're bringing jobs to another part of the UK where manufacturing decline has left things very depressed. Liam Fraser, who was still at school when he first came across the Pi, has done a load of volunteering for the Foundation, and has got a year's work with a company in Cambridge off the back of that, and a much more impressive university application form. People are building businesses around the Pi; we think entrepreneurship makes the world spin, so it's wonderful to watch that happening. And, of course, there are the jobs that have come to Wales as a result of the Pi. That's probably the single thing that makes me proudest.

Oh -- and last year, Steve Furber [principal designer of the BBC Micro and the ARM microprocessor] shook my hand and told me I was doing a great job. Serious hero-worship moment.

BN: You’ve got a camera board coming out in April that will allow Pi users to build video applications. Any other similar add-ons planned?

LU: We're looking at a display board too, but that's currently in the very early stages.

BN: What does the future hold for the Pi -- new versions?

LU: The Foundation's committed to making sure that we don't suddenly up-sticks and change the platform under people's feet: the open community has been very good to us, and the last thing we want to do is to make the work they've done on the available software redundant. We want to continue selling the Raspberry Pi Model B for a good long time yet; we do have a final hardware revision to make, but the platform will be set in stone after that. We don't have plans to make a new Pi at the moment; what we are putting a lot of effort into is improving the software stack. We reckon there are orders of magnitude of performance increases we can shake out of Scratch, for example; and this isn't stuff you can expect the community to do, because it's a very long and fiddly job. So Scratch, Wayland, Smalltalk: you should see some big improvements coming over this year. We're also switching a lot of our concentration to our educational mission this year, after a year spent scrambling to get on top of manufacture.

Photo credit: gijsbertpeijs

Many people use Really Simple Syndication without actually realizing it. Like SMTP in the background of email, RSS is the backbone of a number of things, including the podcasts you get from the iTunes store. Last week Google set off on an apparent challenge to kill RSS, or at least it seems that way to many of us.

Many people use Really Simple Syndication without actually realizing it. Like SMTP in the background of email, RSS is the backbone of a number of things, including the podcasts you get from the iTunes store. Last week Google set off on an apparent challenge to kill RSS, or at least it seems that way to many of us.

The tiniest of details can sometimes lead to the thorniest of problems, which Google may discover with its brand new Nexus 10 ad which debuted today. The video seems innocent enough -- it follows a young couple through nine months of pregnancy as they plan for their new bundle of joy and discuss what to name the baby boy.

The tiniest of details can sometimes lead to the thorniest of problems, which Google may discover with its brand new Nexus 10 ad which debuted today. The video seems innocent enough -- it follows a young couple through nine months of pregnancy as they plan for their new bundle of joy and discuss what to name the baby boy. I’m a huge fan of Raspberry Pi, the super-affordable ARM GNU/Linux computer that’s bringing programming back into schools (and beyond). In one year alone, more than a million Pis have been sold globally, which is a phenomenal achievement, and demand for the uncased credit card-sized device shows no signs of abating.

I’m a huge fan of Raspberry Pi, the super-affordable ARM GNU/Linux computer that’s bringing programming back into schools (and beyond). In one year alone, more than a million Pis have been sold globally, which is a phenomenal achievement, and demand for the uncased credit card-sized device shows no signs of abating. Microsoft is rolling out an updated Skype app for Windows Phone 8 devices featuring integration with the People Hub. The latest move comes nearly two weeks after the software giant teased a similar feature for Outlook.com, which touts

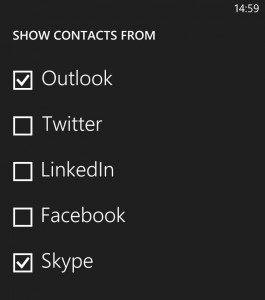

Microsoft is rolling out an updated Skype app for Windows Phone 8 devices featuring integration with the People Hub. The latest move comes nearly two weeks after the software giant teased a similar feature for Outlook.com, which touts  But what does the new Skype integration entail? Windows Phone 8 users can now look up Skype contacts in the People Hub and initiate video and voice calls as well as chats. Users who want Windows Phone 8 to forgo displaying the adjacent contacts should open the People Hub, go to Settings, select "filter my contacts" list and untick "Skype".

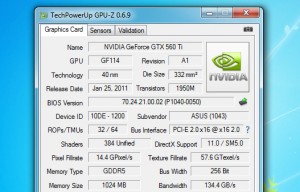

But what does the new Skype integration entail? Windows Phone 8 users can now look up Skype contacts in the People Hub and initiate video and voice calls as well as chats. Users who want Windows Phone 8 to forgo displaying the adjacent contacts should open the People Hub, go to Settings, select "filter my contacts" list and untick "Skype". TechPowerUp has released

TechPowerUp has released  Otherwise, though,

Otherwise, though,  Microsoft's ongoing process to improve the company's cloud platform, Windows Azure, has reached a new phase. The software giant has, yet again, introduced a number of new features for Windows Azure, including the HDInsight service for Hadoop clusters, support for Dropbox deployment and Mercurial repositories, as well as enhancements to Mobile Services.

Microsoft's ongoing process to improve the company's cloud platform, Windows Azure, has reached a new phase. The software giant has, yet again, introduced a number of new features for Windows Azure, including the HDInsight service for Hadoop clusters, support for Dropbox deployment and Mercurial repositories, as well as enhancements to Mobile Services. Microsoft is making another attempt to get into the Chinese market by way of something

Microsoft is making another attempt to get into the Chinese market by way of something  US mobile operator Verizon has announced that

US mobile operator Verizon has announced that  Open-source Windows file management tool

Open-source Windows file management tool