By Angela Gunn, Betanews

Let's get something clear up front: Whatever you've heard elsewhere, Microsoft doesn't intend for their Vine service to take over your Twitter or your Facebook or your texting or any of your other social networking tools. They've got bigger fish to fry.

Let's get something clear up front: Whatever you've heard elsewhere, Microsoft doesn't intend for their Vine service to take over your Twitter or your Facebook or your texting or any of your other social networking tools. They've got bigger fish to fry.

Back in 2005, as we watched Hurricane Katrina upend our faith in America's emergency response system, some Microsoft folk started asking what software development might bring to the table in future crises. Tammy Savage, general manager for Microsoft's public safety initiatives, says that the original Vine team spent a lot of time thinking about "all aspects of crisis, from preparation to recovery -- all kinds of organizations, asking what Microsoft might uniquely be able to provide."

Note the word "uniquely," which would let out Twitter-replacement and the like. So is Vine an aggregator, combining a bunch of data streams in the way Facebook can include Twitter or Trillian combines all your instant messaging? Again, think unique, think bigger, and think about the company involved.

How large is your social network, anyway? Here's the answer: Smaller than Microsoft's, if you regard all the constituencies they touch as constituencies to which they are networked. Though, as Savage puts it, "we didn't go in with the assumption we can help," scrutiny of the organizations and entities involved in a disaster ("first responders, emergency management, humanitarian organizations, critical infrastructure, consumers..." and Savage's list went on) showed the Vine team a role they might undertake and "a sustainable investment" in filling it.

And so the Vine aggregation picture starts to become clearer -- Twitter and Facebook and instant messaging and text and e-mail and local news and weather data and... well, let's give Microsoft some air to figure that out. Right now, the project is entering what Savage refers to as "an old-fashioned" (private, access-controlled) beta, with approximately 10,000 participants drawn mainly for now from the Seattle area. Those participants include the City of Seattle, Boeing, Microsoft itself, national service organizations, neighborhood watch groups, Americorps, volunteer coaches, fire departments, and so on.

![Front panel of Microsoft's first beta of Vine. [Photo credit: Microsoft Corp.]](http://images.betanews.com/media/3212.jpg) So it's also not the Emergency Broadcast System, which has also already been invented. "There are a lot of top-down alerts" out there, Savage notes. "This is a complement to that. Information from sources we trust isn't always top-down information." Your spouse, for instance, doesn't have the information one could get from the local traffic cameras, but s/he is the world's leading authority on whether s/he is running late for dinner, and Vine can adapt accordingly.

So it's also not the Emergency Broadcast System, which has also already been invented. "There are a lot of top-down alerts" out there, Savage notes. "This is a complement to that. Information from sources we trust isn't always top-down information." Your spouse, for instance, doesn't have the information one could get from the local traffic cameras, but s/he is the world's leading authority on whether s/he is running late for dinner, and Vine can adapt accordingly.

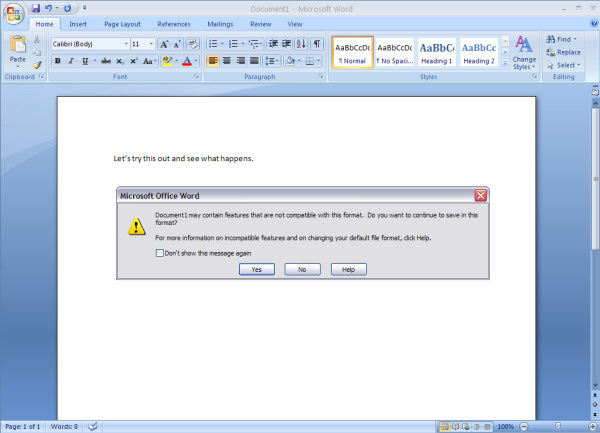

The service has three components. The dashboard -- the main interface -- is map-based and culls location-specific information from over 20,000 news and official information sources. Your main contacts appear there too when they post something or otherwise update their status.

Beyond the dashboard, there are alerts and reports, both of which can go out to individuals or, more usefully, contacts you're grouped together (e.g., The Neighbors, My Students, Family). Reports are sent dashboard-to-dashboard, while alerts can be sent to any device the recipient chooses, so you don't have to remember that Mom prefers text messages while your boss would rather get an IM in a crisis, and by Vine application, text or e-mail.

Now about crises, which is how this conversation started. For every individual in each of your groups, there's not only a different set of information sources with which one would want to keep in touch, but quite likely a different set of situations that would constitute a crisis. For instance, the chief of police probably doesn't care that your kids' usual soccer practice field is too muddy to use this evening, and your Facebook pals don't all need to know that you're heading out of town and need a neighbor to keep an eye on the house.

Vine can handle those variations, which is where some of the confusion over social networking comes in. In fact, variations are sort of the point. You may be someone who groups your IMs and Twitters and so forth for ease of perusal, but in an emergency, ease becomes a ruthless push to prioritize. Though no one will discourage you from trying, using Vine as currently conceived to simply ride herd on an unruly friends list seems a bit like taking an Uzi to a knife fight.

Or maybe not. For now, Microsoft doesn't have all the answers about how people will use Vine. Though Savage has some nice examples of using alerts in ordinary sub-critical situations, there's a lot to discover about real-world use as situations rise and fall. "Right now we're focused on listening," says Savage, explaining how the beta period will operate -- not open to just anyone, but if you've got an invite of your own, you can invite others. (Very, um, social.)

As the system develops, there will be myriad tech problems to address -- especially, considering its public emergency emphasis, the problem of staying connected if all hell really is breaking loose. Though the beta currently requires broadband, Windows, and a Live ID account, that won't always be the case, Savage says. Of equal significance is Vine's need to not rely entirely on Internet connectivity. "The product roadmap takes into account that some communications systems won't work," says Savage. "Internet, mesh networks, peer-to-peer, satellite mobile phones, landlines, SMS -- we need to create a system that's smart and inclusive."

Testing is expected to build out to other locations soon, and the site is taking signups for beta invitations. Pricing's uncertain, though as Savage points out, there's almost always concern with a project this big about "what the business looks like."

[Photo credit: Microsoft Corp.]

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2009

Validating the news we received last week of the

Validating the news we received last week of the ![A network application that requires Windows XP appears to run fine in Windows 7 under 'XP mode' virtualization. [Photo credit: Microsoft Corp.]](http://images.betanews.com/media/3209.jpg)

Weighing in at 22 ounces, the K-Light is water-resistant, shatterproof, and mercury-free, according to Meyer. The side handles rotate 360 degrees, and can be locked into 12 different positions. Through the proverbial flick of a switch, you can set the 120-lumen LED for either maximum brightness, with a 10-hour runtime before solar recharging, or for less brightness, with a 20-hour runtime.

Weighing in at 22 ounces, the K-Light is water-resistant, shatterproof, and mercury-free, according to Meyer. The side handles rotate 360 degrees, and can be locked into 12 different positions. Through the proverbial flick of a switch, you can set the 120-lumen LED for either maximum brightness, with a 10-hour runtime before solar recharging, or for less brightness, with a 20-hour runtime.

The site is still young, and there is a lot of space for growth as users submit more tests. However, user submissions are not the central attraction of Hunch. It was started as an exploration of machine learning and how it can be used in practical decision making. All user submissions and decisions are being used in a Hunch core algorithm that ranks results according to how appropriate they are to each user.

The site is still young, and there is a lot of space for growth as users submit more tests. However, user submissions are not the central attraction of Hunch. It was started as an exploration of machine learning and how it can be used in practical decision making. All user submissions and decisions are being used in a Hunch core algorithm that ranks results according to how appropriate they are to each user.

"What services that consumers consider essential to the safe and efficient functioning of the Internet are advanced by DPI?" asked Boucher during his opening remarks yesterday. "Since the death of

"What services that consumers consider essential to the safe and efficient functioning of the Internet are advanced by DPI?" asked Boucher during his opening remarks yesterday. "Since the death of ![AMD 4/22/09 platform update slide [Courtesy AMD Corp.]](http://images.betanews.com/media/3186.jpg)

![AMD 4/22/09 platform update slide [Courtesy AMD Corp.]](http://images.betanews.com/media/3187.jpg)

PBS has unveiled

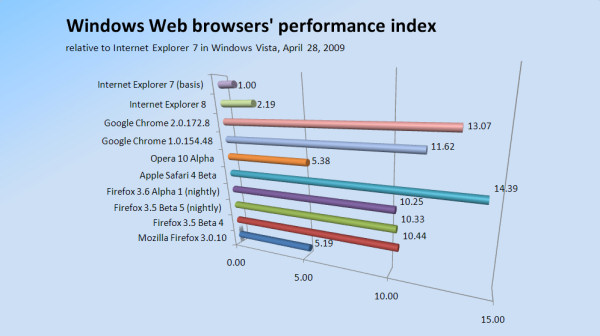

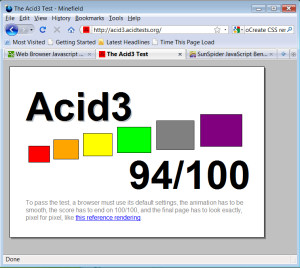

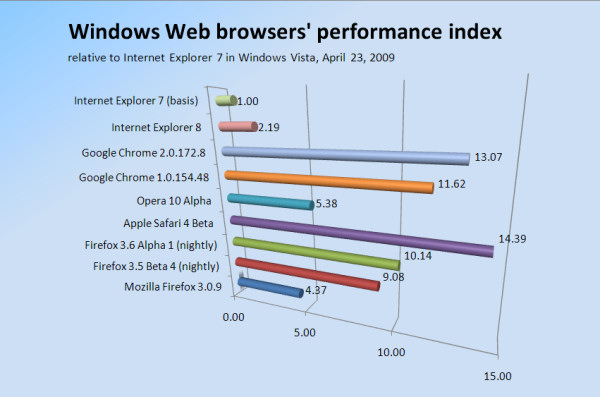

PBS has unveiled  Our tests pit the latest Windows-based Web browsers in a virtual Vista system, and combine the Acid3 standards test with three trusted performance tests for CSS rendering and JavaScript speed. Nearly all the early news for the 3.6 alpha was good, including posting Mozilla's best-ever score on the Acid3 test -- a 94% -- and posting a Betanews cumulative index score for the first time above 10.0, which means this alpha performs over ten times better than Microsoft Internet Explorer 7 (not the current version, IE8, but the previous one).

Our tests pit the latest Windows-based Web browsers in a virtual Vista system, and combine the Acid3 standards test with three trusted performance tests for CSS rendering and JavaScript speed. Nearly all the early news for the 3.6 alpha was good, including posting Mozilla's best-ever score on the Acid3 test -- a 94% -- and posting a Betanews cumulative index score for the first time above 10.0, which means this alpha performs over ten times better than Microsoft Internet Explorer 7 (not the current version, IE8, but the previous one).

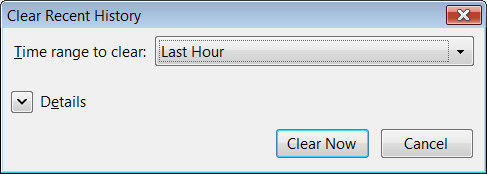

Once we stop tinkering with the accelerator pedals for a minute or two, we might get a chance to play with some of 3.6's new features. We did stumble across one of them right away: When clearing your history and the contents of the browser cache, you can now specify generally how much time you want to wipe clean -- the last hour, two hours, four hours, today, or everything in the cache. Now, at the moment, this comes at the expense of specifying what you want to wipe clean -- history, cache, cookies, passwords -- but perhaps the team is looking for a way to integrate those choices into the new setup.

Once we stop tinkering with the accelerator pedals for a minute or two, we might get a chance to play with some of 3.6's new features. We did stumble across one of them right away: When clearing your history and the contents of the browser cache, you can now specify generally how much time you want to wipe clean -- the last hour, two hours, four hours, today, or everything in the cache. Now, at the moment, this comes at the expense of specifying what you want to wipe clean -- history, cache, cookies, passwords -- but perhaps the team is looking for a way to integrate those choices into the new setup.

About about that Anglo-Saxon language excursion there near the end: The subject was engineering, or more specifically how the people who actually do something useful at Yahoo are currently crushed under the weight of multiple layers of product managers -- one manager for every three engineers, she estimates. Bartz agrees that it's excessive: "We have a lot of people running around here telling engineers what to do, but no one is f*****g doing anything."

About about that Anglo-Saxon language excursion there near the end: The subject was engineering, or more specifically how the people who actually do something useful at Yahoo are currently crushed under the weight of multiple layers of product managers -- one manager for every three engineers, she estimates. Bartz agrees that it's excessive: "We have a lot of people running around here telling engineers what to do, but no one is f*****g doing anything."

![JournalismOnline.com co-partner and former Wall Street Journal editor L. Gordon Crovitz. [courtesy JournalismOnline.com]](http://images.betanews.com/media/3165.jpg) L. Gordon Crovitz, partner,

L. Gordon Crovitz, partner,

As we mourn the passing of the first great Internet company (into the maw of Larry Ellison), academics are gathering in Barcelona for the

As we mourn the passing of the first great Internet company (into the maw of Larry Ellison), academics are gathering in Barcelona for the

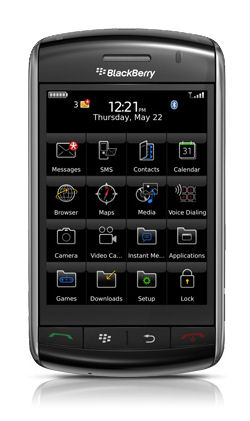

Okay, so the font file itself is still in the system, but you won't actually use it or want it. The old system fonts looked like something spat out of a Centronics dot-matrix printer, circa 1978. I remember selling dot-matrix printers in the early days, including one of the first to offer a switch that converted you from "sans-serif" to "serif," or in that particular case, from "legible" to "illegible." Until today, we 8800 users had something called "BBClarity" (which at least meant, devoid of junk) and "BBMilbank," which looked like it belonged on one of those programmable highway warning signs, shouting, "BEWARE OF ZOMBIES."

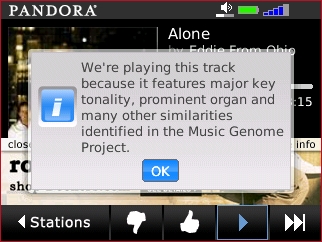

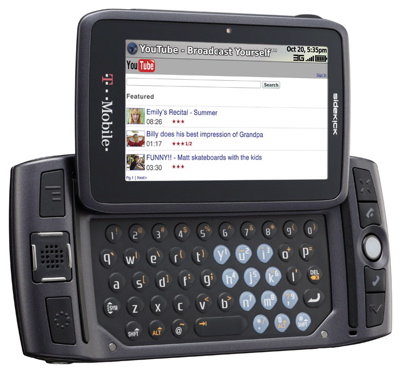

Okay, so the font file itself is still in the system, but you won't actually use it or want it. The old system fonts looked like something spat out of a Centronics dot-matrix printer, circa 1978. I remember selling dot-matrix printers in the early days, including one of the first to offer a switch that converted you from "sans-serif" to "serif," or in that particular case, from "legible" to "illegible." Until today, we 8800 users had something called "BBClarity" (which at least meant, devoid of junk) and "BBMilbank," which looked like it belonged on one of those programmable highway warning signs, shouting, "BEWARE OF ZOMBIES." One of those apps is the mobile edition of Pandora, the original programmable radio stream that learns your musical tastes as you listen. Having Pandora in my pocket is reason alone to own a mobile handset; my friend Angela

One of those apps is the mobile edition of Pandora, the original programmable radio stream that learns your musical tastes as you listen. Having Pandora in my pocket is reason alone to own a mobile handset; my friend Angela  The Mobile Pandora isn't as conversational as the PC edition -- for instance, you can't go into your profile and load up all your bookmarks. You can get an explanation why you're hearing the song you're hearing, and this little feature alone shows you why the System upgrade was necessary -- on the old system, there's no way this information would be the least bit legible in a single alert box.

The Mobile Pandora isn't as conversational as the PC edition -- for instance, you can't go into your profile and load up all your bookmarks. You can get an explanation why you're hearing the song you're hearing, and this little feature alone shows you why the System upgrade was necessary -- on the old system, there's no way this information would be the least bit legible in a single alert box. The upgrade process will back up your existing calendar, e-mail, media, and personal applications automatically, and will restore them after the new modules are loaded in and verified. The verification process, for some reason, is the longest stage -- be prepared to wait as long as 45 minutes. The process in its entirety could take an hour, maybe a little longer.

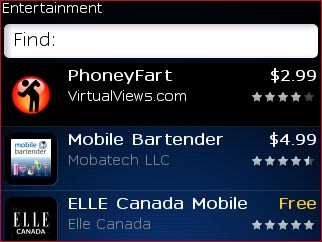

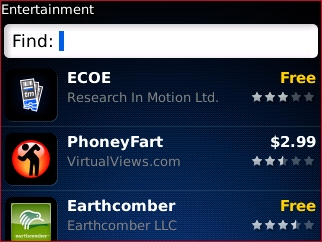

The upgrade process will back up your existing calendar, e-mail, media, and personal applications automatically, and will restore them after the new modules are loaded in and verified. The verification process, for some reason, is the longest stage -- be prepared to wait as long as 45 minutes. The process in its entirety could take an hour, maybe a little longer. You'll notice some differences right away, some thanks to the new system, others on account of smart users who truly appreciate the low value of farting apps. The catalog is much more pleasant to read, even if -- sadly -- some of the entries haven't changed all that much since App World's premiere earlier this month. The "before" and "after" pictures above tell the story. ("ECOE" isn't very self-explanatory, is it? It's a Ticketmaster application, so you'd think it would have been named something like "Ticketmaster Application.")

You'll notice some differences right away, some thanks to the new system, others on account of smart users who truly appreciate the low value of farting apps. The catalog is much more pleasant to read, even if -- sadly -- some of the entries haven't changed all that much since App World's premiere earlier this month. The "before" and "after" pictures above tell the story. ("ECOE" isn't very self-explanatory, is it? It's a Ticketmaster application, so you'd think it would have been named something like "Ticketmaster Application.")

Whether it's a new investment tack or simply goodwill to the technology community in a down economy, early-stage venture capital firm

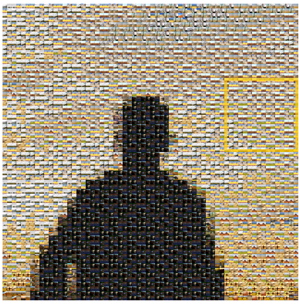

Whether it's a new investment tack or simply goodwill to the technology community in a down economy, early-stage venture capital firm  You know those composite picture mosaics, where thousands of individual photographs are combined into a single, large image? National Geographic Digital Media has debuted a photo community tool that creates an infinitely zoomable loop of that sort called

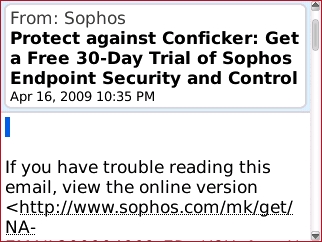

You know those composite picture mosaics, where thousands of individual photographs are combined into a single, large image? National Geographic Digital Media has debuted a photo community tool that creates an infinitely zoomable loop of that sort called  Conficker

Conficker  Repeating his belief that

Repeating his belief that

Comm. Reding addressed one aspect of the social networking data problem in her address this morning: "Social networking has a strong potential for a new form of communication and for bringing people together, no matter where they are. But is every social networker really aware that technically, all pictures and information uploaded on social networking profiles can be accessed and used by anyone on the Web? Do we not cross the border of the acceptable when, for example, the pictures of the

Comm. Reding addressed one aspect of the social networking data problem in her address this morning: "Social networking has a strong potential for a new form of communication and for bringing people together, no matter where they are. But is every social networker really aware that technically, all pictures and information uploaded on social networking profiles can be accessed and used by anyone on the Web? Do we not cross the border of the acceptable when, for example, the pictures of the  Korean software company EYA Interactive announced the upcoming "Grand Opening Beta" of its Free MMORPG called

Korean software company EYA Interactive announced the upcoming "Grand Opening Beta" of its Free MMORPG called  It should be no surprise, especially to long-time Mac users, that noted analyst Roger L. Kay, currently with Endpoint Technologies, is a supporter of the Windows "ecosystem." His opinions with regard to Windows are very much on the record, and he and I have often joined together with our colleagues, in brisk, lively, but fair discussions about the relative value of software and hardware on different platforms.

It should be no surprise, especially to long-time Mac users, that noted analyst Roger L. Kay, currently with Endpoint Technologies, is a supporter of the Windows "ecosystem." His opinions with regard to Windows are very much on the record, and he and I have often joined together with our colleagues, in brisk, lively, but fair discussions about the relative value of software and hardware on different platforms. Kay's current message plays very well to Microsoft's current marketing message for Windows-based PCs...eerily well. In the last several days prior to the release of Kay's white paper,

Kay's current message plays very well to Microsoft's current marketing message for Windows-based PCs...eerily well. In the last several days prior to the release of Kay's white paper,  On Monday,

On Monday,

"It is critical that our plan be competitively and technologically neutral," wrote McDowell yesterday (

"It is critical that our plan be competitively and technologically neutral," wrote McDowell yesterday (