The Indiana Legislature is in the news for passing a state law considered by many to be anti-gay. It reminded me of the famous Pi Bill -- Bill #246 of the 1897 Indiana General Assembly. There’s a good account of the bill on Wikipedia, but the short story is a doctor and amateur mathematician wanted the state to codify his particular method of squaring the circle, a side effect of which would be officially declaring the value of π to be 3.2.

The Indiana Legislature is in the news for passing a state law considered by many to be anti-gay. It reminded me of the famous Pi Bill -- Bill #246 of the 1897 Indiana General Assembly. There’s a good account of the bill on Wikipedia, but the short story is a doctor and amateur mathematician wanted the state to codify his particular method of squaring the circle, a side effect of which would be officially declaring the value of π to be 3.2.

The bill was written by Representative Taylor I. Record, sent to the Education Committee where it passed, went back to the Indiana House of Representatives where it again passed, unopposed. Then the bill went to the Indiana Senate where Professor C.A. Waldo of the Indiana Academy of Science (now Purdue University) happened to be visiting that day to do a little lobbying for his school. Professor Waldo explained to the Senators the legislative dilemma they faced.

Then, according to an Indianapolis News article of February 13, 1897:

…the bill was brought up and made fun of. The Senators made bad puns about it, ridiculed it and laughed over it. The fun lasted half an hour. Senator Hubbell said that it was not meet for the Senate, which was costing the State $250 a day, to waste its time in such frivolity. He said that in reading the leading newspapers of Chicago and the East, he found that the Indiana State Legislature had laid itself open to ridicule by the action already taken on the bill. He thought consideration of such a proposition was not dignified or worthy of the Senate. He moved the indefinite postponement of the bill, and the motion carried.

Given that the bill was postponed, not defeated, I suppose it could be revived and passed today. Almost anything is possible in Indiana.

Speaking of the law, a number of readers have asked me to comment on the Ellen Pao v. Kleiner Perkins gender discrimination case that was resolved last week in San Francisco. I don’t have much to say except that I think the verdict was the right one. This is not to say that the VC industry doesn’t have problems in this area but that Kleiner Perkins is probably the best of the bunch and therefore was the worst possible target.

That’s my logical reaction. My emotional reaction is quite different because I spent all last week as part of a large jury pool in Sonoma County Superior Court for a case of statutory rape. The rape victim was a middle schooler who had two babies (two pregnancies) with a man probably 30 years her senior. The girl’s mother was charged as an accomplice. What this has to do with the Pao case is I could catch on my phone breathless live blogs of the Pao courtroom play-by-play from both the San Jose Mercury and Re/Code, yet the Santa Rosa rape case has yet to be noticed by any news media anywhere, I guess until now. In this era of supposed news saturation and citizen journalism that’s not the way it’s supposed to be.

I was on the jury for about five minutes before I was dismissed by the prosecution.

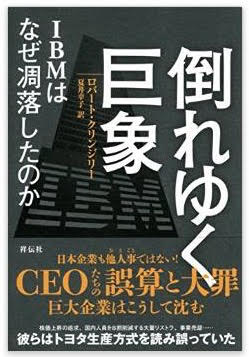

Finally, a revised and somewhat updated version of my IBM book is out now in Japanese! Here (in English) is the Preface for the Japanese Edition:

Why should Japanese readers care about the inner workings of IBM? They should care because IBM is a huge information technology supplier to Japanese industry and government. They should care because IBM Japan is a large employer with thousands of Japanese workers, most of them highly-paid. They should care because, of the American multinationals, IBM has always been the most like a Japanese company with strong corporate discipline and lifetime employment. Only IBM chose Japanese managers to run its subsidiary, making it not just IBM’s office in Japan but also Japan’s office at IBM.

But times have changed. IBM no longer offers its workers lifetime employment. And many other aspects of the company have changed, too. Some of these changes have been in response to economic forces probably beyond IBM’s control, but others can be traced directly to IBM management abandoning the principles under which the company was run for many decades.

IBM is a very different company today from what it was 10 or 20 years ago. That’s what this book is all about — how IBM has changed and why. It is not a happy story but it is an important one, because IBM is a bellwether for all its peers — peers that include big Japanese companies, too.

IBM has lost its way. This book explains how that happened and why. And while IBM is nominally an American company, the impact of this change is felt everywhere IBM does business, including Japan.