With the recent announcements of password breaches at LinkedIn, and warnings from Google about state-sponsored attacks on Gmail accounts, it seems like a good idea now to review some password security basics. Then there is report today that someone hacked presidential candidate Mitt Romney's Dropbox and Hotmail.

In this post, we’re going to take a look at a rather low-tech solution to a decidedly high-tech problem: How to guard against password reset attacks, and where to securely store the answers to your password reset questions.

Even if you use highly secure passwords, it is possible someone might still be able to compromise your account if they were able to gather enough information about you to know -- or at least guess -- the answers to your password reset questions. Many services use the same questions, e.g., your mother's maiden name, the name of the town you were born in, the name of first pet and so forth. Because similar questions are used over and over again to reset passwords, it can be fairly easy, even somewhat boring, for an attacker who gathers this type of information to use it to gain access to all sorts of accounts one might have, across services ranging from those which are purely social to financial institutions, or even identity theft. The reported Romney hack is about someone guessing the answer to one of his security questions.

Password Reset Hack Attacks

Sometimes, though, it’s even simpler than that: An example of this is former Alaskan governor Sarah Palin, whose personal Yahoo! mail account was compromised via password reset using data about her available from public resources. Of course, most people are not going to have enough biographical data available online to make such an attack easy. Or do they?

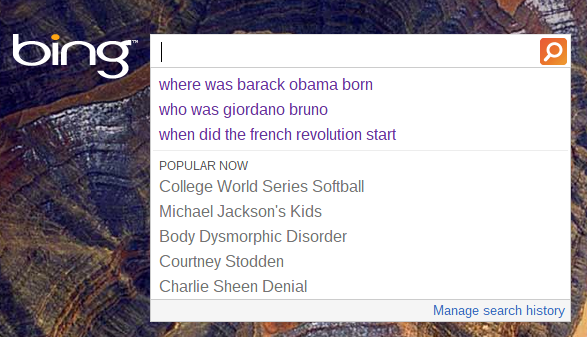

With the rise of social networking has come a kind of blurring of the sorts of personal information it’s okay, and safe, to put online. Eager to generate more revenue, social media sites encourage, and in some cases may even require, people to share information about themselves such as birthdays, hometowns, where they went to school and so forth. While this is the sort of information we readily share with friends and family, social media companies request it because it allows for more targeted advertising. The fact that it is the same type of information needed to perform an attack or an impersonation is not something those companies typically tell you about when asking you to fill out your profile, or warn you that profile is not complete.

To date, I cannot recall any criminals going after aggregate personal data en masse in order to perform password reset attacks. Data breaches typically provide the password themselves or other information that can be readily used for identify theft, such as birth dates, information about credit cards and, in some cases, even social security identification numbers.

Defending Your Passwords

But even if you are not a politician, celebrity or somewhere between the two, you should still take steps to safeguard your privacy and, these days that means some creativity is needed when filling out online forms, such as when filling in the answers to questions used to reset a password.

One of the largest problems is, of course, deciding exactly what to enter. In the case of birthdates, some websites, such as online stores, might require you to enter your birthdate so they can send you a birthday offer or as the answer to a password reset question. They have no other reason for asking for this information, though, and there’s no guarantee they will keep this information secure or use it for other purposes, including selling it to marketing firms. On the other hand, there are plenty of web sites -- financial, insurance and government all come to mind -- where you may not only need to enter your correct birth date but you may be obligated to give them the correct information.

There’s also another issue to consider, both for you and the website, and that’s the issue of ethical behavior. Knowingly providing false data to a website is something of a gray area, even if there is no legal requirement not to do so. How does your obligation to provide a website with correct information balance with your right to freedom from the theft of that data, let alone the issue of privacy? Measuring these competing, and often contradictory, needs is something everyone has to do for themselves, and we cannot make the decision for you. You will need to decide if breaking this social contract is justified as a matter of practical protection.

If you have made the decision not to enter your actual birthdate, than what should you enter? The correct month and day of your birthdate, but the wrong year? The correct year, but with January 1st as your date of birth? The date of your favorite holiday? Making the answers to your password reset questions as unique as your passwords is the key to protecting against attacks on them, so using the same answer over and over again is out: That simply provides another widely-disseminated piece of information for a criminal to collect during the data aggregation phase of the attack.

One Low-Tech Solution

There is a solution, though, and it is a decidedly low-tech one: Write them down in a small notebook (that is, the kind you write in with a pen or pencil, not a laptop computer). Or, if you are not partial to keeping a little black (or orange) book, a business card or recipe card holder filled with index cards works just as well, too. Store your little “code book” in the area near, but not directly at, the computer, preferably in a location where it is at least out of site. The ubiquitous junk drawer works well for this purpose. Of course, if you use a computer in a shared area, you might want to look at storing your code book in a locked desk drawer, filing cabinet or safe.

Now that we have discussed what to use your code book for and where to place it for safekeeping, exactly what sort of information should you write in it? I would recommend something along the following lines:

- name of website

- username

- date you signed up for the service

- answer(s) to password reset questions

- date of last password change (and/or date of next password change)

For additional security, do not store the actual answers to your password reset questions, but rather mnemonics or clues that will tip you, but not an attacker, to the answers.

During the course of writing this blog post, I came across the rather descriptively-named Personal Internet Address & Password Log Book, which, as the name implies, is a place to store information about your website and email accounts. It does, however, contain fields to enter the actual passwords, and not the answers to the questions used to reset those passwords.

Regardless of whether you choose to store password reset questions or the actual passwords, it’s important to keep in mind, though, that the physical security of any written-down information in your notebook -- whether it be the passwords themselves or just the responses password reset challenges -- is paramount: Writing down that information is the equivalent to putting your passport, driver’s license, social security card, check book, credit cards and debit cards (and their PINs) all together in one convenient bundle.

If you do not have a place that is physically secure enough to store a password reset notebook in, you should not use one for this purpose. Keep in mind that an accident or disaster could result in the notebook being destroyed or unavailable, and plan accordingly. Another thing to keep in mind is that as a tangible, physical object, your password reset notebook is subject to loss. Making a copy of it with a photocopier and storing that offsite in a secure location like a safe deposit box is far less risky than scanning it and storing the copy on your PC where an attacker can access it.

Reprinted with permission.

Photo Credit: urfin/Shutterstock

Aryeh Goretsky is distinguished researcher for security provider ESET. He is responsible for a variety of activities, including threatscape monitoring, investigating new and emerging technologies, working with ESET's developers, QA and support engineers, and liaising with other research organizations. He was the first employee at McAfee Associates and is a veteran of several software and networking companies. A Microsoft MVP since 2004, he runs the C-SQUAD mailing list for law enforcement and IT professionals.

Aryeh Goretsky is distinguished researcher for security provider ESET. He is responsible for a variety of activities, including threatscape monitoring, investigating new and emerging technologies, working with ESET's developers, QA and support engineers, and liaising with other research organizations. He was the first employee at McAfee Associates and is a veteran of several software and networking companies. A Microsoft MVP since 2004, he runs the C-SQUAD mailing list for law enforcement and IT professionals.

Microsoft's Office 365 cloud productivity suite gained even more momentum on Thursday, with both the Department of Transportation and Federal Aviation Administration announcing they will move some 80,000 employees to the platform.

Microsoft's Office 365 cloud productivity suite gained even more momentum on Thursday, with both the Department of Transportation and Federal Aviation Administration announcing they will move some 80,000 employees to the platform.

Irving Fain is the CEO & Co-founder of

Irving Fain is the CEO & Co-founder of

Building a website which looks good on desktop computers and mobile devices generally requires a lot of thought. There are plenty of design issues to consider, and even when you think you’ve finished you’ll still need to test the site thoroughly to confirm that all is well. (Just browsing a few pages with your iPad almost certainly won’t be good enough.)

Building a website which looks good on desktop computers and mobile devices generally requires a lot of thought. There are plenty of design issues to consider, and even when you think you’ve finished you’ll still need to test the site thoroughly to confirm that all is well. (Just browsing a few pages with your iPad almost certainly won’t be good enough.)

It’s important for your PC’s security to install application updates just as soon as they become available, but if a program doesn’t check for these itself then that can be a challenge. Unless you have the time to monitor every application website yourself then you’ll probably need some third-party help, and the latest candidate is the free and portable

It’s important for your PC’s security to install application updates just as soon as they become available, but if a program doesn’t check for these itself then that can be a challenge. Unless you have the time to monitor every application website yourself then you’ll probably need some third-party help, and the latest candidate is the free and portable

Red Hat moved its hybrid cloud management software called CloudForms out of beta on Thursday, aiming to allow IT customers with considerable infrastructure to leverage it with public cloud resources to enable easy migration between the two.

Red Hat moved its hybrid cloud management software called CloudForms out of beta on Thursday, aiming to allow IT customers with considerable infrastructure to leverage it with public cloud resources to enable easy migration between the two.