Joe Wilcox argues that TechCrunch produces boatloads of original content using a method called process journalism. In counterpoint, "TechCrunch just exposed what is wrong with tech journalism today", Ed Oswald contends that the blog is rife with conflict of interest and questionable news reporting ethics.

Have you been on the Internet long enough to remember Global Network Navigator -- yeah, that's GNN. It was the first web portal I used to get news and quick access to other useful sites. O'Reilly & Associates (now O'Reilly Media) launched the site in 1993. AOL bought GNN in 1995 and closed it in 1996, quite unceremoniously. The domain is still active and points to Huffington Post. Old-time Netters will remember GNN and a long list of other properties and products purchased by AOL that were later abandoned or closed -- all part of a decade-and-a-half plan to reinvent as a new media company.

Another AOL acquisition is on the hit list. TechCrunch, rather than writing tech news, is tech news following several days of tumultuous commentaries both inside and outside the organization. The AOL property, acquired in September 2010 for $30 million, is ripe for major shakeup. What was good about TechCrunch could be gone by year's end; heck by the end of the week, if core staffers bolt or are canned. Love him or hate -- and there seems to be little between these emotions -- TechCrunch founder Michael Arrington is out, or soon will be in the inevitable AOL slaughter.

Arrington's fate, and that of TechCrunch, was certain in February 2011, when AOL announced the $315 million acquisition of Huffington Post. It was never a question of if but when things would change. There isn't room enough for two big blog media personalities at AOL, particularly with such opposing worldviews about news acquisition.

About 90 minutes after I posted, Arrington made a startling admission and demand of AOL:

"I believe that AOL should be held to their promise when they acquired us to give TechCrunch complete editorial independence. As of late last week TechCrunch no longer has editorial independence. Some argue that the circumstances demanded it. I disagree. Editorial independence was never supposed to be an easy thing for AOL to give us. But it was never meaningful if it shatters the first time it is put to the test".

Perhaps editorial independence looked easier 12 months ago, before AOL handed over control of its blogs to Huffington. Arrington:

"We’ve proposed two options to AOL.

1. Reaffirmation of the editorial independence promised at the time of acquisition. Given the current circumstances, that means autonomy from Huffington Post, unfettered editorial independence and a blanket right to editorial self determination. To put it simply, TechCrunch would stay with AOL but would be independent of the Huffington Post.

or

2. Sell TechCrunch back to the original shareholders.

If AOL cannot accept either of these options, and no other creative solution can be found, I cannot be a part of TechCrunch going forward".

My content below takes on richer context in light of Arrington's official response to AOL.

The Huffington Way

Ariana Huffington is the queen of news aggregation, and it is a heap successful business model that many long-time journalists loathe. Huffington also is queen of free; the site summarizes news content many other organizations pay some writer to produce. The practice is now widespread, as other sites imitate the aggregation-by-summarization model.

By contrast, TechCrunch mostly produces original content, which is an increasing rarity on the web, particularly among blogs. There has been fierce debate about Arrington's ethics -- running a site that reports news about companies he invests in -- but few critics can legitimately argue that TechCrunch doesn't produce boatloads of original content. From that perspective, TechCrunch is a model of traditional journalism and values of in-depth, original reporting.

But that's not the kind of content company AOL wants to be, and that's warning to other profile AOL acquired blogs -- Engadget and The Unofficial Apple Weblog. Already, Engadget had a mass exodus of senior staff, following the Huffington Post acquisition, to form a new tech news site. Engadget editor Paul Miller left within 10 days of the acquisition. The Huffington Postification of AOL media sites had begun.

Last month, AOL CEO Tim Armstrong couldn't gush enough about Huffington Post, in the media company's second-quarter earnings press release and on the conference call. "The Huffington Post traffic surpassed The New York Times during the quarter and passes nearly 10 million monthly unique users", Armstrong said. AOL launched 17 new sites during the quarter, mostly from the Huffington Post Media Group. "In the consumer side area, we launched AOL Healthy Living, Huffington Post Canada and Huffington Post U.K., Huffington Post Women, Huffington Post Celebrity, Huffington Post Parent, Huffington Post BlackVoices", Armstrong said. "We've been very busy in the content business".

The AOL Way

Change is inevitable at AOL, which has been trying to reinvent as a media company since the mid 1990s. GNN was one of the earliest casualties. In her November 1996 SFGate.com news story on the closure, Julia Angwin wrote about the "little-known GNN": It "actually helped make the World Wide Web a household name". That's a fact. As did the more visible Netscape, which AOL bought and later killed, just as browser competition was starting to pick up again. The company has smart sense for good products or properties but often doesn't understand what to do with them, once it has them.

Overnight, TechCrunch's MG Siegler wrote overly-whiny "TechCrunch may be over as we know it":

"This is a post I never thought I’d have to write. Unfortunately, I do. And the worst part about it is that it should be Michael Arrington writing this post, not me. But he can’t. TechCrunch is on the precipice. As soon as tomorrow, Mike may be thrown out of the company he founded. Or he may not. No one knows...

By now, if you read TechCrunch, you likely know about the nuclear situation that has exploded over the past several days. Mike unveiled an investing entity known as the 'CrunchFund' with full AOL support -- so much support, mind you, that they’re the largest backers of the fund -- only to have his legs kicked out from under him due to what can only be described as nonsensical political infighting and really poor communication. To make matters worse, some Journalists (with a big “J” and even bigger senses of entitlement) have".

Siegler explains how he sees TechCrunch differences from traditional journalism in a personal blog post. He attributes the news blogs' success to its lose organizational structure.

The Arrington Way

I see more fundamental reasons for the site's success. By my observation of TechCrunch business practices, Arrington, who is an attorney by trade, applies lawyer’s ethics to the blogging operation. Lawyer principles seek to protect client relationships. Pretty much anything else is OK, except disclosing information clients share with the attorney. Journalists protect sources, which isn't so dissimilar, but are obliged by other ethical standards obligations -- like getting the facts straight. Lawyers are not bound by such principles and they often misrepresent things to benefit their clients. Lawyers are notorious for floating out trial balloons -- information, misinformation or rumors to gauge somebody’s reaction. TechCrunch regularly floats trial balloons by way of rumor stories. The blog uses rumors to advance the reporting process. The stories generate helpful comments and other leads.

Traditional journalists are expected to get the facts right before a story is published. TechCrunch takes a different approach. "Stories evolve on our blog", Arrington explained in June 2009. "It can start with a rumor, which we may post if we find it credible and/or it’s being so widely circulated that the fact of the rumor’s existence is newsworthy in itself. But then we evolve a post to get to the truth".

There's a name for it: process journalism, which Jeff Jarvis, associate professor of journalism at City University of New York, explained two summers ago. Print journalism is obsessed with perfection. A story isn’t ready until it is authoritatively written and fact checked, which makes sense when the medium is print. The story needs to be nearly as perfect as possible. Jarvis explains about the myth of perfection held by journalism and some other industries:

"If you have just one chance to put out a product and it has to serve everyone the same, you come to believe it’s perfect because it has to be... Online, the story, the reporting, the knowledge are never done and never perfect. That doesn’t mean that we revel in imperfection…It just means that we do journalism differently, because we can. We have our standards, too, and they include collaboration, transparency, letting readers into the process, and trying to say what we don’t know when we publish -- as caveats, rather than afterward -- as corrections".

For TechCrunch, the process can be surprisingly good reading. I haven’t done an official count, but I’d guess that TechCrunch posts more unfinished stories than the more complete kind published by, say, the New York Times. TechCrunch stories evolve -- and, I must assert, too often from unsubstantiated rumors. It’s a process I must grudgingly acknowledge that TechCrunch can be quite transparent about. The process, of the story unfolding over time, produces original content that often is interesting reading, and readers participate in that process, through comments and other social media tools.

AOL puts that process at risk. Where Huffington Post processes news stories like pieces of coal moving down an assembly line, TechCrunch uses process journalism to produce diamonds. Which is more valuable? They both have their place, but as a journalist I'll take TechCrunch over Huffington Post every day of the year.

Photo Credit: Joi Ito

Music creation software has something of a poor reputation, with many people regarding it as being expensive to buy and complicated to use. This is a reputation that MAGIX is trying to change with its Music Maker program, and the latest version, MAGIX Music Maker MX goes a long way to achieving this aim. While the program is incredibly simple to use, the music creation you produce using the software can be made as basic or as complex and involved as you like.

Music creation software has something of a poor reputation, with many people regarding it as being expensive to buy and complicated to use. This is a reputation that MAGIX is trying to change with its Music Maker program, and the latest version, MAGIX Music Maker MX goes a long way to achieving this aim. While the program is incredibly simple to use, the music creation you produce using the software can be made as basic or as complex and involved as you like.

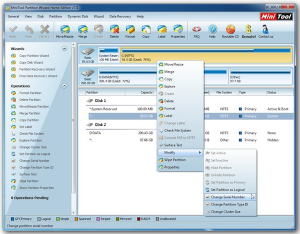

MiniTool Solution Ltd has released a brand new version of its non-destructive partitioning software. MiniTool Partition Wizard 7.0, available as a free-for-personal-use

MiniTool Solution Ltd has released a brand new version of its non-destructive partitioning software. MiniTool Partition Wizard 7.0, available as a free-for-personal-use  On the last day of August, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit in the District of Columbia to block the proposed merger of national wireless network operators AT&T and T-Mobile. Tuesday, competing national carrier Sprint Nextel announced it had filed a similar antitrust suit in federal court, saying the $39 billion merger is, in short, illegal.

On the last day of August, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit in the District of Columbia to block the proposed merger of national wireless network operators AT&T and T-Mobile. Tuesday, competing national carrier Sprint Nextel announced it had filed a similar antitrust suit in federal court, saying the $39 billion merger is, in short, illegal.

The hacker who breached the DigiNotar certificate authority

The hacker who breached the DigiNotar certificate authority