By Scott M. Fulton, III, Net1News

The promise of Hauppauge's HD PVR digital recording device is that it will enable you to use the expensive television signal being piped into your house, on your own terms. Just a few years ago, it seemed, it was easier for most folks to be able to use that signal however and whenever they wanted, and TiVo blasted open the doors for people with busy lives to start, stop, restart, collect, and re-watch the programs that made the intervening hours between crises somewhat enjoyable.

But since then, the restraints and constraints started re-appearing -- the same-room recording restrictions, the "broadcast flags," the availability constraints, the second-run and third-run limitations that make lower-class viewers wait for upper-class viewers to be served first. As studios and content providers act on their second thoughts about opening up digital availability, "on demand" is becoming more of a misnomer. Perhaps "on plea" is more appropriate.

Hauppauge HD PVR, available for $199 through hauppauge.com

"I don't know about you, but my cable TV bill is close to $200 a month. For $200 a month, I want to be able to record my programs, to watch them whenever I want, and not be limited to recording in one room and having to watch in that same room," said Ken Plotkin, the CEO of Hauppauge Computer Works (pronounced "Hup-hog," for all you non-New Yorkers), in an interview with Betanews. "We think that multi-room DVR is the next step in allowing consumers to be able to get access to the kinds of programming that they want to watch, no matter where they are or what time it is. I can tell you that all of the consumers that I've spoken to, including my family and friends, feel that the DVR has been a life-changing experience. . . We believe that the technologies that both the PC [device] manufacturers like Hauppauge and the consumer electronics manufacturers like TiVo have delivered to the consumer market have been, if not life changing, at least experience changing for most consumers."

The truth is, the television viewing "experience" has been changing on an ongoing basis, both before and since the onset of TiVo. Since US broadcasters have completed their shift to digital over-the-air transmission, cable companies have been stepping up their efforts to shift their customers towards (artificially) costlier digital receivers. As a result, not only are fewer (or no) channels available through analog cable lines in many communities, but fewer (or no) channels are being made available through the general-class digital service known as ClearQAM. This is the space Comcast and other cable providers have delegated for the carriage of their local service areas' broadcast signals, as they are compelled to do by law. By removing basic cable channels such as USA and CNN from ClearQAM, the segment of cable spectrum occupied by broadcasters become automatically cast as second- or third-class, bargain-basement, less desirable. And that seems to be the plan, especially for cable service providers that are themselves becoming larger content providers as well.

So what was perfectly recordable television circa 2008 using home-grown equipment, including Hauppauge WinTV cards, suddenly became out of reach in 2009 and '10. As early as 2005, Intel and AMD began enticing builders with the idea of "media PCs," home entertainment complexes that provided access to thousands of digital sources, each on an equivalent basis with one another, all under the user's direct control. Then the asterisks started appearing beside "direct control," as HDTV and STB manufacturers began adopting HDMI, and content providers took advantage of their opportunity to limit the way consumers made "extended use" of the digital signals they were paying for.

Although recording and non-commercial viewing of a signal constitute "fair use" under US copyright law, consumers who bought into the media PC idea found themselves taking extraordinary measures to be able to reuse the content riding those signals in a fair way. When Windows Media Center first premiered with Windows XP, the STB industry was not very pleased. It took the initiative not of Microsoft but of individual engineers like Tim Moore to make Media Center work with a Firewire cable just to change the STB's channels; and periodically, Microsoft and others took steps to undo those initiatives with driver releases and security updates. Today, even though Media Center is one of the key selling points of Windows 7, few customers can actually use it to control all, or in some cases even any, of the television they're paying for.

Hauppauge HD PVR shows its excitement by glowing as it records.

HD PVR is another of those "extraordinary measures" available to consumers: a wedge that people can drive into the digital pipeline to re-enable the fair use that the very design of their system would otherwise deny them. It isn't a piracy device or a reverse-engineering of the digital signal. In fact, it doesn't even record the digital signal: It takes advantage of the analog connections that many consumers use between their tuners and HDTVs, to siphon off image and sound that can then be re-recorded digitally. It's not stealing anything, nor is it actually recording anything of commercial resale quality.

And contrary to its appearance, it doesn't even include its own hard drive. You supply the PC and the recording media; HD PVR is essentially an analog signal interception device with software. Because it leaves room for so many component cables (YPbPr), composite cables (RCA stereo), and optical cables, it can't all fit on a PC card or USB thumb device like Hauppauge's well-known tuners. Once plugged in, HD PVR looks less like a hi-fi component and more like a portable cardiac monitor. In my house, where a visitor is likely to find any number of boxes I've built with wires hanging out of them, it doesn't look so out of place. But frankly, despite Hauppauge's best efforts to make it attractive -- including the airport runway-like blue LED canals along the upper ridge that glow while it's recording -- most home entertainment component owners will probably want to keep this thing tucked away and out of sight.

Next: Wedging WinTV into Windows

Wedging WinTV into Windows

Setting up the physical components of HD PVR is almost academic. It ships with a set of YPbPr component cables that connect to your STB; the cables that formerly connected your TV to the STB, now connect to the back of the HD PVR. Then a USB cable is all that's left to attach to the PC.

At this point, you should have plenty of hair remaining to pull out during Hauppauge's software installation process (I don't, at least not anymore, but I suppose that goes with my lifestyle choice). I'm a tester by nature, and on purpose, I don't make things easy on the component I'm testing, because there are no guarantees that a user in the real world will be in an easier situation than mine. I had already built my own media PC around a Gigabyte motherboard with an Intel Core 2 6600 CPU, in which I'd already installed a superb Hauppauge WinTV HVR-2250 tuner card. It's a fabulous double-dual tuner literally capable of recording two HD ClearQAM signals, and two standard-def analog signals, simultaneously (of course, I tried that myself once for the heck of it, and yes, it really does). With fewer ClearQAM channels available on my Comcast line, unfortunately, I'm now only able to use the HVR-2250 to record HD broadcast channels. However, the recording quality for those channels is outstanding, a very visible difference from the Comcast line, as you'll see for yourself momentarily.

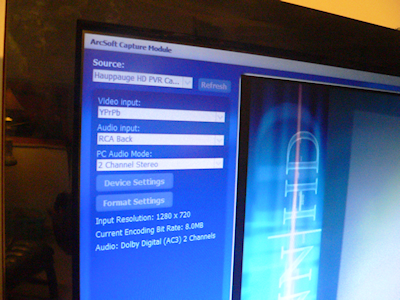

At first, I tested HD PVR using the software that shipped with it: a set of WinTV-branded drivers (the presence on the CD of some of which, I suspect, is redundant since HD PVR is not a tuner but a capture device) and recording software called ArcSoft Total Media Extreme. Just to keep things difficult for myself, my intention was to leave the HVR-2250 card in the system, partly because I didn't want to lose my ability to record at least some television using Windows Media Center (which, perhaps by happy accident, may go down as some of the best software Microsoft has ever produced), and partly because I wasn't looking forward to the headaches that come with installing Hauppauge drivers. Anyone who has ever owned a Hauppauge product deserves a medal for endurance, although the quality and typically flawless performance of Hauppauge's tuner hardware has always been a reward in itself.

As predicted, making the two Hauppauge products co-exist was bizarre. The version of the WinTV driver that powers the HVR-2250, and the version that powers HD PVR, appeared to be different versions that could not co-exist. After installing the HD PVR software, Total Media Extreme appeared to work fine. Later, I discovered that the HVR-2250 was not working at all; Media Center believed it was still there, but every channel was dead air. I thought, sadly, that the HVR-2250 would have to go, at least for the duration of this test. I uninstalled its software and removed the card, but was then baffled to discover HD PVR failed to work. I uninstalled HD PVR's software, cleaned Hauppauge from the Registry completely, and then reinstalled it -- still nothing.

For reasons which may very well be inexplicable, HD PVR will now only work in my test system with HVR-2250 present, if the WinTV software is installed in this order: HD PVR first, then HVR-2250 on top without uninstalling the newer software first. My guess is, this is a symptom of all the hoops Hauppauge hardware and software have to jump through in order to make any digital recording on a PC possible in the first place.

I did have some trouble getting the sound capture to work properly, which required me unplugging and re-plugging the sound cables until I heard something. Strangely, I discovered that the STB would not send either video or audio to the HDTV with the computer turned off. Once working properly, you still have to have the front HD PVR switch turned on, even when your computer is off, for the HDTV to receive a signal from the STB -- which makes sense, because the capture device is interrupting the signal and needs to be powered.

Next: "Extreme On" and "Extreme Off," off and on

"Extreme On" and "Extreme Off," off and on

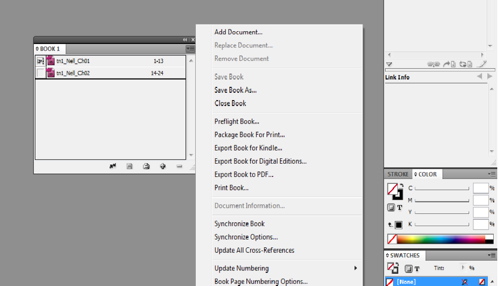

"Total Media Extreme" bats an 0.333 in the name department. There is nothing particularly total or extreme about it, any more than a wall-based light switch provides "total illumination extreme," or a spoon provides "total cuisine extreme." In terms of functionality, it has less than your average 1990s VCR (countless numbers of which I somehow still own). With it, you get a preview window of the video signal from the STB (the tuner). You can start or stop recording from that window, and you can set a timer ahead of time to do the same; but it records whatever the STB happens to be tuned to at the moment.

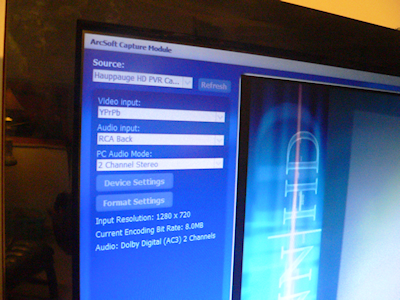

You can change the input source for the signal entering the HD PVR, which is handy if you use HD PVR to transcribe the contents of your camcorder using the alternate composite inputs on the front -- one of HD PVR's very best and most useful features, especially if you find yourself owning a digital camcorder whose drivers fail to work with Windows 7. (Gee, I wonder whom I might be referring to here. . .)

You can change the input source for the signal entering the HD PVR, which is handy if you use HD PVR to transcribe the contents of your camcorder using the alternate composite inputs on the front -- one of HD PVR's very best and most useful features, especially if you find yourself owning a digital camcorder whose drivers fail to work with Windows 7. (Gee, I wonder whom I might be referring to here. . .)

To give the PC more functional control over the STB, Hauppauge does provide IR Blaster software and an infrared cable -- stuff with which diehard PC media aficionados are already too painfully familiar. To make this setup work, you connect the cable to the back of the HD PVR, then find the precise square millimeter of space on the front of your STB beneath which the infrared receiver is lurking, and duct-tape the stem of the IR Blaster cable to that spot. (Duct tape contains the only adhesive that can withstand the extreme temperature changes between a 68-degree room at night, and a 71-degree room during the day, over a six-week period.)

Despite having chosen only the most premium duct tape for the job, I never got IR Blaster to work with Total Media Extreme, not once. As you'll see later, that's not because my Motorola DCH-3200 STB (the LTD Crown Victoria of tuners) isn't capable of handling IR Blaster.

Although it can automatically encode recorded video for playback on PlayStation 3 (M2TS format MPEG-2) or Xbox 360 (MPEG-4), I found that the most reliable format TME supports, capable of being played back without hitches on Windows Media Player and other programs, is the AVCHD (.TS) format originally intended for camcorder compatibility. WMP did not like some of the MP4 files TME produced, and QuickTime liked none of them, although in my tests, they could be imported into video editing software such as Magix Movie Edit Pro 16.

At any event, I was relegated to operating TME manually, including whenever I wanted to record an HD channel that wasn't on ClearQAM. If you already have your own media PC, you already know that it's pointless to set it for sleep mode after so many minutes or hours of use -- that could disrupt a recording or keep a recording from ever happening. That's why my media PC's power profile is set to never shut anything down but the screen after 15 minutes of non-media-player idle time. Total Media Extreme is not Windows Media Player, so you might find yourself watching something through its playback window, and then suddenly the screen shuts off -- you haven't touched it for 15 minutes.

But that's not the cause of Total Media Extreme's biggest problem: On my test system, it freezes between 90 and 120 minutes of continuous recording about one-third of the time. It never freezes on a one-hour show, but it can freeze 80% of the way or longer through a long movie. By "freeze," I mean that the signal from the STB hangs in the preview window, there's no sound, the program is inoperable, and Windows remains active except Task Manager cannot force the program to exit.

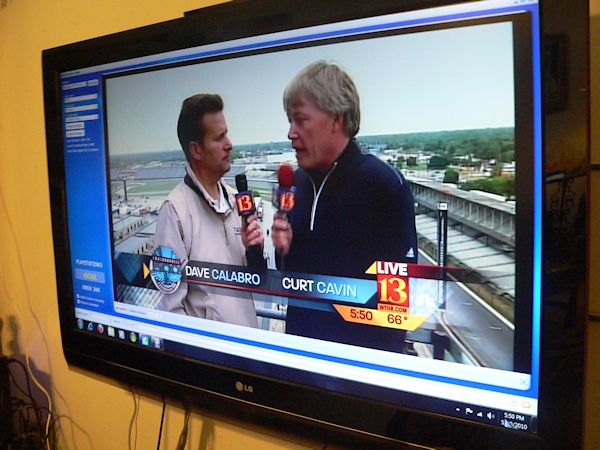

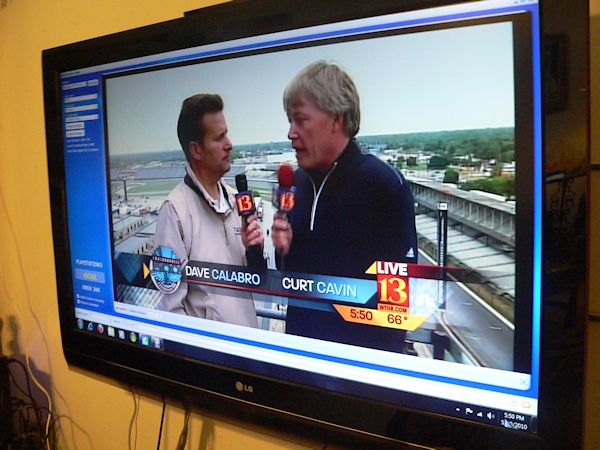

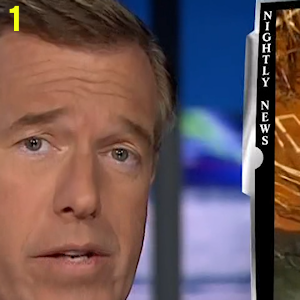

However, I was able to perform one test that clearly demonstrates the qualitative difference between an HVR-2250 recording of a ClearQAM signal, and an HD PVR recording of the same channel on Comcast's crowded digital cable spectrum. If ever you've needed undeniable proof that Comcast compresses its HD channels to the extent that further use of the term "high definition" may be inappropriate, here it is.

Click on a segment to see the screenshot in its entirety. WARNING: Large file, lossless PNG.

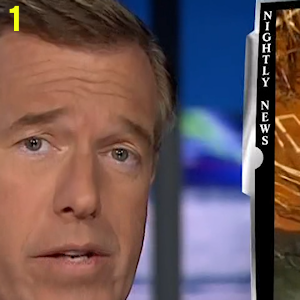

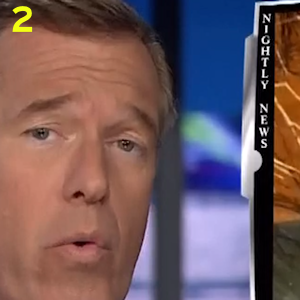

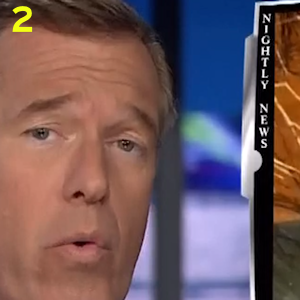

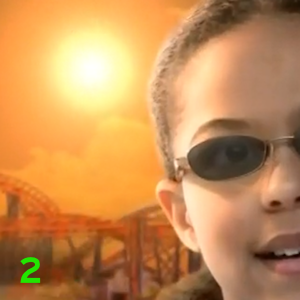

The example screenshots here were taken from the same NBC Nightly News broadcast, each less than a tenth of a second apart one another, but from two separate recordings made simultaneously (proof, at least, that the two Hauppauge parts can work together). For both pairs, Example 1 is from HVR-2250, Example 2 from HD PVR. These captures were made with lossless PNG format, so any compression you see here is on account of the actual recording, not the screenshot.

Click on a segment to see the screenshot in its entirety. WARNING: Large file, lossless PNG.

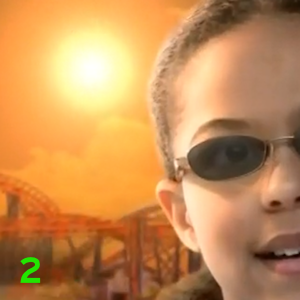

The HD PVR/Comcast Digital Cable screen is by no means unwatchable, at least at this particular moment. And certainly MPEG-2 compression has reared its ugly head on many an occasion for both Digital Cable and Comcast ClearQAM, especially during touchdown passes. But take a good look at the crisp edges of white letters on a black background in the ClearQAM capture, that are shattered as if by a blackboard eraser in the Digital Cable capture. Look at Brian Williams' well-combed sideburns, which in Digital Cable are flattened out to a grey swatch of cardboard. Notice the details that simply vanish in the Digital Cable capture, like the spokes of the Ferris wheel and the grilles of the roller coaster. Look closely at the crisp rim of the girl's left eyeglass in ClearQAM, which becomes a jagged staircase in Digital Cable.

This is the key problem when using any kind of analog signal capture device on a digital cable signal: The recording quality can only hope to be as good as that of the recorded signal, which isn't much. It's ironic that CE manufacturers and content providers should both go to such great lengths to limit your ability to record their pristine, unblemished digital signal, prior to their compressing it into lower resolution than a Piet Mondrian painting.

Next: The forced marriage of HD PVR and Windows Media Center

The forced marriage of HD PVR and Windows Media Center

It's fair to say that operating HD PVR using the software that ships with it, is far from the "immersive media experience" so poetically described by PR experts during the Consumer Electronics Show each year. More to the point, it's like using Windows. It's for people who enter text in boxes, twiddle scroll wheels, and click on OK. It probably bothers me the least of anyone on Earth, at least when everything works (and in my case, not everything did). But when my wife first saw me testing HD PVR, she was so excited that she asked whether she could install it upstairs on her system and try it out. At first, she blamed the look on my face on greed and avarice, rather than a rational desire to protect her sanity. Then she watched me wrestling with the Registry entries for the drivers for all of about three minutes, and exclaimed, "Jeez, what was I thinking?"

What made Windows Media Center such a good piece of software (as well as systems derived from that software, such as Zune) is that it's the least like Windows of anything Microsoft's ever made. It's painless and simple, and it makes sense right up front. To this day, I find folks discovering it in their Windows installations who are rendered speechless by its usability, who didn't even know it was sitting there, waiting on their PCs for upwards of four years.

"I think that devices have to be easier to use -- they need to be push-button," Hauppauge CEO Ken Plotkin told me. "I think it's unacceptable for consumers to have to configure and install and set up and things like that; it's got to be much, much easier. And in fact, a lot of the products that we're working on are going to be much easier to use."

The perfect recording solution, if there is one, would be for Hauppauge HD PVR to be operable through Windows Media Center. This way, a user could tune her STB through Media Center's program grid, by way of Microsoft's Media Center remote (which comes with HVR-2250, and is one of the best designed remotes you'll ever own) without touching the mouse or twiddling any gadgets or on-screen devices.

Making these two powerful components work together comprised most of Hauppauge's development schedule this past spring. Betanews was honored to be part of at least the first part of the beta cycle for the company's new Media Center driver (mitigating circumstances sadly forced us to bow out of the latter stages).

Actually, marrying HD PVR with Media Center is actually more of a ménage a trois, the crowd-forming party in this case being the set-top box. Media Center is perfectly capable of managing multiple video sources simultaneously, but HD PVR is a mostly passive device by design. It can't be the tuner, but Media Center has to "believe" it is.

Step 1 in the installation process for Hauppauge's Media Center package is actually de-installation -- getting rid of the old HD PVR driver. Although Hauppauge's instructions clearly state this as Step 1, they don't give a user any pointers or tools with which to do that. You will find the HCWCLEAR.EXE removal utility on Hauppauge's Web site, but only if you're looking for it (or if we give you the link). If you have another Hauppauge device installed, however (as I do), this utility will get rid of that too.

At first, I tried simply uninstalling the old driver from Device Manager, but as learned, that's not enough. Media Center won't recognize HD PVR as a tuner unless the old driver is gone and the Registry entries for WinTV are wiped clean, which apparently only happens after removing all the WinTV entries (there are at least three) from Programs and Features. If you don't remove those WinTV programs completely, then Media Center could think it recognizes your HD PVR device, but when it operates the channel changer, it'll show you dead air. (Total Media Extreme can stay, however, though you might end up never using it.)

Step 2 involves the downloading of two drivers, from this page and this page. Installation instructions may be downloaded from this second page.

Installing the new software comprises the next three steps, the third of which is the least fun and requires that duct tape. For step 3, the new HD PVR Capture Device driver goes on first, and does not go through the lengthy WinTV installation process, so it's much quicker. The only set of questions you'll be asked is about the inputs; if you use the cables Hauppauge supplied you with, you'll choose YPbPr and RCA Front (back). Step 4 has you add what Windows will recognize as the HD PVR Tuner Device, which is the part that connects with Media Center. That's painless.

Step 5 involves installing the IR Blaster cable, which is the red LED hanging by a hair, that you tape to the STB. When you don't know what point on the STB contains the infrared receptor, and the IR Blaster setup software doesn't have a model name attached to the code for your device (which can happen even when you own one of the most common models in America), the process can resemble submarine warfare, sweeping over patches of real estate top-to-bottom and pinging your best guess for the code number along the way. (My Motorola DCH-3200 is Cable Set-Top Box code 0125, by the way).

Step 6 involves making Media Center scan for available channels. If you've done everything correctly up to now, TV Setup should recognize your digital cable source and identify it on-screen, like in the photo above. You won't know whether it's a recordable source, however, until after the full setup process is complete. If you've done everything carefully up to this point, and IR Blaster did not have your STB's product code off-hand, then you've probably expended four hours of work time.

What you have, once all is said and done, is a tuning and recording process that may as well be set up between devices stationed on different planets. It can work, but sometimes not on the first try, and it's not really anyone's fault -- not Hauppauge's, not Microsoft's, not Obama's.

Okay, it might be Comcast's.

Here's the deal: It takes a few seconds for Hauppauge's driver to decode the signal coming in from the STB. Using Total Media Extreme's preview window, you can actually calculate this delay using the STB's native remote control: Press any key on the remote, and measure the interval in-between the keypress and the on-screen response. At most, that interval can be about three seconds. When you're simply watching TV, that's not a qualitative difference; but when you're trying to get three components to behave nicely with one another, it is.

In a recent upgrade to Comcast's system software, several of its HD channels received alternate mappings -- aliases, in a sense -- to four-digit channel numbers, all of which are bunched together. This way, when you surf the four-digit realm, you won't run into any pesky SD channels along the way. Because of this remapping, it can take several seconds for the tuner in the STB to pick up a new channel once it's dialed up -- especially the four-digit channels, but even the three-digit ones as well.

Say you're watching a three-digit channel on your STB, and either you or Media Center dials up a four-digit channel. The time it takes for IR Blaster to key in all four digits may exceed Media Center's internal timeout, so it can either dial up the wrong channel (the first three digits) or no channel at all. In the first case, Media Center won't "know" it's on the wrong channel since HD PVR is a passive device. The text could clearly read, "Indianapolis vs. Washington," but the screen might clearly show Cary Grant vs. Joan Fontaine.

Add that to the three-second natural delay for decoding the signal, and you have a situation where it may take up to 20 seconds (!) for a channel change event to conclude with a clear signal -- maybe the right channel, maybe not.

Through IR Blaster's setup program, you can reduce the number of milliseconds in-between digit presses, to limit the chance of this channel mismatch. However, if you turn down the delay too much, IR Blaster could input something that isn't a digit at all. In any event -- whether it's IR Blaster punching in a long string of digits too slowly, or speeding it up and triggering a signal that the STB can't decipher, or simply taking too long to pull a signal from out of the cable company's substitute for thin air -- the STB ends up tuning in a blank void. HD PVR, seeing no signal coming in from the STB, sends no signal at all to the computer -- not blackness, but rather nothing at all. That makes Windows Media Center conclude that the service as a whole no longer exists.

Finally, in a scene reminiscent of when Windows 95 used to uninstall your printer driver as a service to you whenever you unplugged it from your parallel port with it turned on, Media Center can suddenly come to the conclusion that you have no service attached to your HD PVR whatsoever (see below) -- that Comcast has fallen off the planet.

This gets worse: If you try to change a channel or dial up an HD PVR channel at this point, Media Center can actually lock up, requiring a system reboot. Suppose Media Center weren't taking instructions from you; that instead, it was running a schedule of unattended recordings. You won't be there to reboot the PC, so you could end up recording nothing.

So far, I have been able to successfully record a program overnight on a four-digit channel different from the one the STB is tuned to at the moment. I do have to leave the STB turned on (just as you used to have to leave the VCR turned on), because even though IR Blaster has the theoretical capability of turning on and off your STB, I cannot seem to even manually train my Blaster to do this. It will send digits, but not On/Off.

There's no question that operating the HD PVR is an "immersive" experience, though I'm still searching for a realistic metaphor for what it is I'm being immersed in. I have indeed made good use of the device during my tests, including for transcribing an important family video from a suddenly incompatible camcorder. You might consider buying HD PVR just for that functionality alone.

Is it a make-your-own-TiVo? No, I'm afraid not; if you've already had your heart and mind set on TiVo, there's nothing here that should change them. But that might not be a bad thing, for reasons I explain after the jump.

Next: HD PVR's target market: Me

HD PVR's target market: Me

If I have a lifestyle -- a subject which, in and of itself, is debatable -- then it's doubtful that anyone in marketing would want to see it replicated as some sort of model for others to follow. I am the furthest thing from a typical consumer one would ever expect to find, and it must be written on my face. The other day while grocery shopping, a local TV news anchor was stopping customers and asking them their feelings on the state of the economy, for a spot on the afternoon newscast. She passed right by me on the way out of the frozen food section, and I could read the expression in her eyes: "Heck no, not him."

If I have a lifestyle -- a subject which, in and of itself, is debatable -- then it's doubtful that anyone in marketing would want to see it replicated as some sort of model for others to follow. I am the furthest thing from a typical consumer one would ever expect to find, and it must be written on my face. The other day while grocery shopping, a local TV news anchor was stopping customers and asking them their feelings on the state of the economy, for a spot on the afternoon newscast. She passed right by me on the way out of the frozen food section, and I could read the expression in her eyes: "Heck no, not him."

The major problem for media marketing experts today, including for those who stop grocery shoppers to ask their feelings or spending habits for demographic research, is determining how modern-day people "consume media." The very question speaks volumes about the principal misunderstanding such experts have about the way we live. Here in my office, to my immediate left are about a thousand of my favorite books, arranged not very artfully but at least well cared-for, several of which I've inherited from family. Downstairs you'll find my movie collection, more than half of which bears the moniker, "VHS." All of this "content," passed down through the decades, much of it well-loved, has yet to be "consumed" by anyone. I expect most of it to continue to exist three decades from now.

And yet the entertainment and publishing industries today remain besieged with the critical problem of controlling the channels, passageways, and walled gardens through which media is consumed. The idea of me, or you, or anyone "owning" a movie has never sat well in the minds or upon the stomachs of Hollywood studio executives. Even when TV screens were black-and-white, and some of them were round, studio execs were so frightened of the thought of people watching movies from their living rooms instead of cinemas, that in the 1950s for a short time, they actually produced cheap rip-offs of their own films with lesser stars and smaller budgets, just for television. Then in the '80s, what finally gave studios some relief about you watching a recording of a movie whenever you felt like it, was the idea that perhaps they could make some money from you wanting to rent it first. Thus began the whole process of devising, and then controlling, not only the delivery channel through which a movie was delivered to you, but also the quality of the picture and sound, and the length of time you'll be able to continue seeing it.

Three years ago, when I was covering the whole Blu-ray-vs.-HD DVD fracas, and I confronted producers about the likelihood of either format's near-term obsolescence, I was surprised at how many considered that a benefit. It would just make me repurchase the same film in the successor's format. "After all," one studio representative asked me, "how many VHS movies do you still own?" I refrained from embarrassing him with the answer.

It is because of the increasingly adversarial relationship between media's producers and consumers over what we want to see, hear, and read, that devices such as the Hauppauge HD PVR exist. Modern television and my family's lifestyle have evolved in diverging directions. If there is anything worth not only watching but enjoying, it needs to be available during a moment when I can relax; and I can no longer certify the exact time of that moment even 24 hours in advance. Simply because I happened to be free Friday at midnight does not mean I'll be free next Friday at midnight.

If television is to have any value to me at all, it needs to be capable of providing programming of some substantive value, at a time I can control, and in a way that lets me pause and return to it later. This is where my friends typically shout "TiVo" at the top of their lungs; and yes, TiVo does provide some tempting features. But those features are geared towards people who have more free time to invest in television, and I'm not one of them. Besides, I'm seriously analyzing the cost/benefit ratio of subscribing monthly to one service whose benefits I only have time to appreciate in the intervening minutes between the many events in my life.

Television as a medium is changing, and so is the lifestyle of the American working person. For the first time in about 70 years, however, they're not changing in tandem. TV, as the publishers of TV Guide are now painfully aware, no longer provides the scheduling grid around which the rest of the events in people's lives are based. There are too many variables in people's lifestyles today, the existence of which has given rise to the need for TiVo, Windows Media Center, and Hauppauge HD PVR. The good efforts of the fine engineers at Hauppauge to make fair use work for people, are being counteracted by the efforts of content and channel providers who want to bring back under some semblance of control and regularity something which may no longer be controllable anymore. We don't all read literature at the same time, why should we watch the same shows simultaneously?

So one can only watch Hauppauge's efforts with hope, and applaud their achievements even when they're incomplete. HD PVR gives more control to people over the media they've already paid for, than they had before. But to do that, it has to align the wandering stars that are the content providers, the service providers, the CE device manufacturers, and Microsoft. That task may never be complete.

[FULL SEC DISCLOSURE:] Hauppauge Computer Works supplied Betanews with an HD PVR capture device for testing for this article, as well as for participating in the company's Windows Media Center driver beta test program. This device was not provided in exchange for consideration in any way, nor did the fact that Hauppauge supplied the device affect the criteria or judgment used in this review.

Scott M. Fulton, III is the editor and publisher of Net1News.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2010

Streaming video on demand service Vudu will be available on all forms of Boxee in November,

Streaming video on demand service Vudu will be available on all forms of Boxee in November,

For as popular as Roku's streaming set top boxes are, they have had practically zero presence in physical retail stores. That is, until a few weeks ago.

For as popular as Roku's streaming set top boxes are, they have had practically zero presence in physical retail stores. That is, until a few weeks ago.

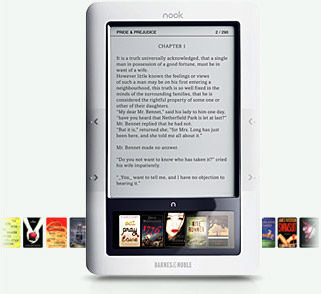

Tueday evening, Barnes & Noble unveiled NOOKcolor, the book retailer's second generation Android-powered e-reader. While the

Tueday evening, Barnes & Noble unveiled NOOKcolor, the book retailer's second generation Android-powered e-reader. While the

Inside the new MacBook Air

Inside the new MacBook Air iMovie `11

iMovie `11 Apple CEO Steve Jobs introduces iLife `11

Apple CEO Steve Jobs introduces iLife `11

You can change the input source for the signal entering the HD PVR, which is handy if you use HD PVR to transcribe the contents of your camcorder using the alternate composite inputs on the front -- one of HD PVR's very best and most useful features, especially if you find yourself owning a digital camcorder whose drivers fail to work with Windows 7. (Gee, I wonder whom I might be referring to here. . .)

You can change the input source for the signal entering the HD PVR, which is handy if you use HD PVR to transcribe the contents of your camcorder using the alternate composite inputs on the front -- one of HD PVR's very best and most useful features, especially if you find yourself owning a digital camcorder whose drivers fail to work with Windows 7. (Gee, I wonder whom I might be referring to here. . .)

If I have a lifestyle -- a subject which, in and of itself, is debatable -- then it's doubtful that anyone in marketing would want to see it replicated as some sort of model for others to follow. I am the furthest thing from a typical consumer one would ever expect to find, and it must be written on my face. The other day while grocery shopping, a local TV news anchor was stopping customers and asking them their feelings on the state of the economy, for a spot on the afternoon newscast. She passed right by me on the way out of the frozen food section, and I could read the expression in her eyes: "Heck no, not him."

If I have a lifestyle -- a subject which, in and of itself, is debatable -- then it's doubtful that anyone in marketing would want to see it replicated as some sort of model for others to follow. I am the furthest thing from a typical consumer one would ever expect to find, and it must be written on my face. The other day while grocery shopping, a local TV news anchor was stopping customers and asking them their feelings on the state of the economy, for a spot on the afternoon newscast. She passed right by me on the way out of the frozen food section, and I could read the expression in her eyes: "Heck no, not him."

Verizon Wireless and Apple today announced that the iPad will be available in 2,000 Verizon Wireless Stores on Thursday, October 28th.

Verizon Wireless and Apple today announced that the iPad will be available in 2,000 Verizon Wireless Stores on Thursday, October 28th.

HTC HD7- 4.3" screen, 720p video, will launch with T-Mobile USA, O2 (UK, Germany,) Movistar (Spain,) and SingTel (Singapore.)

HTC HD7- 4.3" screen, 720p video, will launch with T-Mobile USA, O2 (UK, Germany,) Movistar (Spain,) and SingTel (Singapore.)  HTC 7 Surround - 3.8" screen, slide-out stereo speakers, kickstand, 5 megapixel camera with LED flash Quad-band GSM, Tri-band HSPA; will launch with AT&T (US,) and Telus (Canada.)

HTC 7 Surround - 3.8" screen, slide-out stereo speakers, kickstand, 5 megapixel camera with LED flash Quad-band GSM, Tri-band HSPA; will launch with AT&T (US,) and Telus (Canada.)  HTC Mozart - 3.7" display, Unibody aluminum design; will launch with Orange (France, UK,) Deutsche Telekom AG (Germany,) and Telstra (Australia.)

HTC Mozart - 3.7" display, Unibody aluminum design; will launch with Orange (France, UK,) Deutsche Telekom AG (Germany,) and Telstra (Australia.) HTC 7 Trophy - 3.8" screen, 5 Megapixel LED flash camera; will launch with SFR (France,) and Vodafone (Germany, Spain, UK, Australia.)

HTC 7 Trophy - 3.8" screen, 5 Megapixel LED flash camera; will launch with SFR (France,) and Vodafone (Germany, Spain, UK, Australia.) HTC 7 Pro - QWERTY slider; will launch on Sprint in the US in 2011.

HTC 7 Pro - QWERTY slider; will launch on Sprint in the US in 2011. Samsung Focus - 4" Super AMOLED; noted for being the thinnest Windows Phone 7 device at launch (9.9mm,) 5 megapixel camera, Quad-band GSM, Tri-band HSPA, will launch on AT&T in the US.

Samsung Focus - 4" Super AMOLED; noted for being the thinnest Windows Phone 7 device at launch (9.9mm,) 5 megapixel camera, Quad-band GSM, Tri-band HSPA, will launch on AT&T in the US. Samsung Omnia 7 - 4" Super AMOLED slider; will launch with Orange (France, UK,) SFR (France,) Movistar (Spain,) and Deutsche Telekom AG (Germany.)

Samsung Omnia 7 - 4" Super AMOLED slider; will launch with Orange (France, UK,) SFR (France,) Movistar (Spain,) and Deutsche Telekom AG (Germany.) LG Quantum - 3.5" QWERTY slider; 5 megapixel autofocus camera, Quad-band GSM, Tri-band HSPA; will launch with AT&T in the United States.

LG Quantum - 3.5" QWERTY slider; 5 megapixel autofocus camera, Quad-band GSM, Tri-band HSPA; will launch with AT&T in the United States. LG Optimus 7 - 3.8"; will launch with Telus (Canada,) America Movil (Mexico,) Movistar (Spain,) Vodafone (Germany, Italy, Spain, UK,) SingTel (Singapore,) and Telstra (Australia.)

LG Optimus 7 - 3.8"; will launch with Telus (Canada,) America Movil (Mexico,) Movistar (Spain,) Vodafone (Germany, Italy, Spain, UK,) SingTel (Singapore,) and Telstra (Australia.)  Dell Venue Pro - 4.1" QWERTY portrait slider; will launch on T-Mobile USA.

Dell Venue Pro - 4.1" QWERTY portrait slider; will launch on T-Mobile USA.

Just days before the October 11th deadline, the United Arab Emirates' Telecommunications Regulatory Authority today announced that Research in Motion's BlackBerry services are now compliant with local law and will not be blocked.

Just days before the October 11th deadline, the United Arab Emirates' Telecommunications Regulatory Authority today announced that Research in Motion's BlackBerry services are now compliant with local law and will not be blocked. After almost two years in alpha, Mozilla today finally upgraded its mobile browser Fennec to beta 1 on Android and Maemo. With the upgrade to beta, it sheds the name "Fennec" altogether and grows into full-blown Firefox.

After almost two years in alpha, Mozilla today finally upgraded its mobile browser Fennec to beta 1 on Android and Maemo. With the upgrade to beta, it sheds the name "Fennec" altogether and grows into full-blown Firefox.

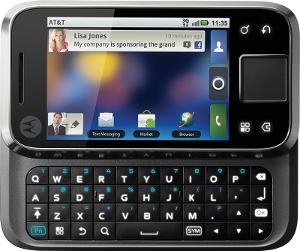

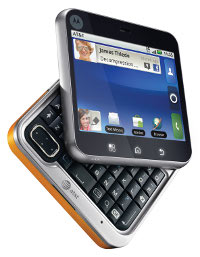

Flipside

This QWERTY slider features a unique large trackpad on the front panel beside the 3.1" touchscreen. It runs a 720MHz processor and Android 2.1, and will be available for $99 on AT&T.

Flipside

This QWERTY slider features a unique large trackpad on the front panel beside the 3.1" touchscreen. It runs a 720MHz processor and Android 2.1, and will be available for $99 on AT&T. Spice

This touchphone is designed for one-handed use, so it features a shorter chassis, has Motorola's Backtrack trackpad on the rear, and a portrait QWERTY keyboard. There was no announcement of Spice coming to the U.S., but Motorola mentioned that the device will be launching in Brazil.

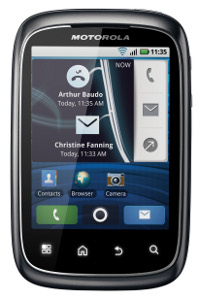

Spice

This touchphone is designed for one-handed use, so it features a shorter chassis, has Motorola's Backtrack trackpad on the rear, and a portrait QWERTY keyboard. There was no announcement of Spice coming to the U.S., but Motorola mentioned that the device will be launching in Brazil. Citrus

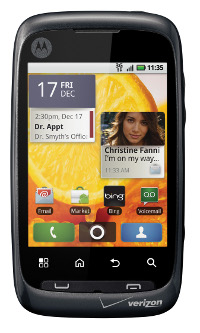

Similar to the Spice, the Citrus is designed for one-handed use and features a Backtrack trackpad, but no QWERTY keyboard. Verizon Wireless will be getting this touchphone, and though pricing has yet to be announced, it is expected to be an entry-level device based upon its modest specs.

Citrus

Similar to the Spice, the Citrus is designed for one-handed use and features a Backtrack trackpad, but no QWERTY keyboard. Verizon Wireless will be getting this touchphone, and though pricing has yet to be announced, it is expected to be an entry-level device based upon its modest specs. Bravo

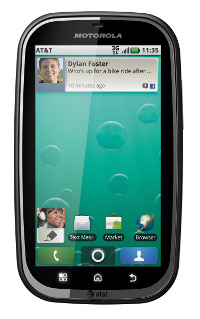

This 3.7" touchphone is bound for AT&T. Running on an 800MHz TI OMAP processor, and equipped with a 3.2 megapixel camera, Bravo will be available for $129.99 this holiday season. It is the most powerful of the three new Android devices AT&T will be getting from Motorola.

Bravo

This 3.7" touchphone is bound for AT&T. Running on an 800MHz TI OMAP processor, and equipped with a 3.2 megapixel camera, Bravo will be available for $129.99 this holiday season. It is the most powerful of the three new Android devices AT&T will be getting from Motorola. Flipout

Like the Charm, Flipout features a 2.8" square screen and square keyboard, but it has a corner hinge which lets the device be folded over. This will be available with AT&T on October 17 and will cost $79.99.

Flipout

Like the Charm, Flipout features a 2.8" square screen and square keyboard, but it has a corner hinge which lets the device be folded over. This will be available with AT&T on October 17 and will cost $79.99. Droid Pro

Droid Pro

October 11, one week from today, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer and AT&T Mobility & Consumer Markets CEO Ralph de la Vega will

October 11, one week from today, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer and AT&T Mobility & Consumer Markets CEO Ralph de la Vega will

Book retailer Barnes and Noble on Monday launched its independent e-book publishing platform Pubit! to attract independent and do-it-yourself publishers to the Nook e-reader.

Book retailer Barnes and Noble on Monday launched its independent e-book publishing platform Pubit! to attract independent and do-it-yourself publishers to the Nook e-reader.