By Scott M. Fulton, III, Net1News

What defines a platform - any platform - in today's market, is apps. If you have apps, you're on the map. If you don't have apps, you're webOS.

Just two short years ago, it would have been unthinkable for anyone to consider the JavaScript engine of any Web browser as the basis for a genuine software platform - something you could make a living from as an apps developer, rather than just a hobbyist. For many, JavaScript was something a Web page used to determine which browser was running, and if it was Internet Explorer, to make it refrain from doing certain dangerous stuff. But in just two years' time, not only have the JS interpreters in Web browsers including IE increased their calculating and processing speed by a factor of ten, but the security of browser-based scripts has improved from almost non-existent to formidable. And all of a sudden, you begin to wonder whether Larry Ellison overpaid for Sun Microsystems.

Now, with the entry of an abundance of third-party, open source libraries, led by the outstanding jQuery library by developer John Resig, coupled with the rapid evolution of several technologies claiming to be part of HTML 5 (despite claims from standard group W3C that HTML 5 hasn't gelled yet), JavaScript looks like a platform that could stand toe-to-toe with both Java and .NET. Meaning, with little or no up-front investment of money, and a rapidly diminishing investment of time for tackling the learning curve, you could conceivably write a linear video editor application on par with iMovie, that's deployed from the cloud, accessed on demand, runs in the browser, and beats any such editor ever released for Windows.

"JavaScript. . . apps" is no longer an oxymoron.

It's here where Opera Software, whose Opera browser has the smallest usage share of the world's top five, has an unprecedented opportunity to cash in. Last year at this time, while its Opera 9 browser performed like a Chrysler K-car at a demolition derby, it premiered an overwhelmingly improved Opera 10.5, literally gift-wrapped with gold and tinsel for the holidays. Goodbye, K-car; hello, Ram pickup. Within just a few weeks, the brand of browser that was facing obsolescence, lagging behind Google Chrome by as much as 600%, was beating Chrome handily.

Just since that time, the performance of development builds of all brands of browsers has at least tripled - in Microsoft's case, quadrupled with IE9. Competition in this market for free software has exploded to such an extent that not even Gordon Moore would be able to write a law that governs it. So today, a statement made back in February 2009 by Opera developer Jens Lindström appears more prophetic than it did at the time:

Referring to the design of Opera's latest "Carakan" JavaScript engine (which Opera sometimes refers to as an "ECMAscript engine" in accordance with standards), Lindström wrote, "Although our new engine's bytecode instruction set permits the implementation of a significantly faster bytecode execution engine, there is still significant overhead involved in executing simple ECMAScript code, such as loops performing integer arithmetics, in a bytecode interpreter. To get rid of this overhead we are implementing compilation of whole or parts of ECMAScript programs and functions into native code."

The precise extent to which Opera is able to compile "whole or parts" of JS programs is something the company doesn't publicly talk about or publicize. Unlike Firefox, Chrome, or the WebKit engine of Safari, Opera is not open source (though it does contain elements that are, and which Opera Software redistributes under open source licenses). So when Opera's performance improves by double-digit factors, it's literally a surprise to everyone outside of the company's headquarters in Oslo, Norway.

Two weeks ago, a snapshot development build of what was being called Opera 10.70 started exhibiting very unexpected behavior, specifically with respect to a particular set of benchmark tests dubbed "SlickSpeed." These tests evaluate a common characteristic of open source JavaScript extension libraries - namely, the ability to logically address elements of a Web page using succinct CSS selectors, as opposed to complex objects. Compared with the stable builds of Opera 10.62 and 10.63, the new snapshot was running these libraries at least twice as fast, and as much as eight times as fast. And with respect to its own built-in CSS element selecting ability, the snapshot was processing instructions eight times as fast as well.

What appears to be happening (which no one at Opera Software, in discussions with me, will confirm or deny) is that the latest build of its JS engine is pre-compiling library code in larger chunks, into native code. Since JS libraries are built intentionally to be reused, the newest Opera appears to be optimizing the runtime speed of those libraries by simply caching their native code in memory and refraining from recompiling them with each reuse.

It's the type of speed jump that one might think would mandate a point release rather than just a refresh. And just as I was about to make that point in an article, Opera beat me to the punch. Starting last Thursday, its alpha builds of the next Opera browser were dubbed Opera 11.

Google has made no secret about its intention to elevate Chrome to the platform level, marketing at least the idea (certainly not the hardware yet) of Chrome as an operating system. To do that, it opened up that browser to extensibility, at least in typical Google fashion - giving "Chrome apps" a single button on an exclusive bar in the browser. For Opera to compete, it not only needs to accommodate "Opera apps" in the engine. It needs to make them accessible through the browser. . . which to date has been something Opera Software is a little touchy about.

"We've supported widgets for a while now, and we've gone through the process of creating a platform for widgets that works, from a speed and a security perspective. We've opened up the technology and made widgets into Web standards," stated Arnstein Teigene, Opera's extensions product manager, in an interview with Net1News. "We've taken a lot of that knowledge and applied that to extensions. So we're inviting people to extend the browser. Widgets tend to live outside of the browser; but now people can develop stuff that sit right inside the browser, which we think is really great from an end user perspective. Of course, you have to be a little bit careful in terms of how you implement it, security- and speed-wise."

Opera has "supported" extensibility in the past, in the way that a toddler "supports" a hot bathtub by sticking just his toes in it and waiting until past midnight to jump in. Back in 2006 with Opera 8, the company implemented a concept it called UserJS (a concept simultaneously tried with a Firefox extension called Greasemonkey). Here, scripts could be set up on the client side to supplement or even override scripts supplied by a Web site, theoretically improving the functionality of existing sites and services. One such UserJS script still seeing action today among Opera users is Autosizer 2 by Arve Bersvendsen, which can effectively make any Web site's display of images into a resizable gallery. It's a useful utility, but one that needs upgrading with almost every new release of Opera, as the company's forums indicate.

There is a kind of UserJS community, but it's based around just a few scripts, and most of the activity seems comprised of users pleading for help. Meanwhile, on a separate development track but also beginning in 2006, Opera enabled the deployment of what it called widgets. Like extensions, they used Opera's JS engine; but unlike extensions at all, they ran outside the browser, and were intended instead to complement the desktop, like Windows Sidebar gadgets. Opera has tried to cultivate a development community around widgets, but as Microsoft itself discovered during the Vista period, just how many clock gadgets, slideshow panes, and network activity meters can a thriving community be expected to produce?

"We've taken a lot of the knowledge that we accumulated from widgets, and applied it to this," Opera's Teigene told us. "As a developer, you can create extensions using Web standards like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. And Opera is the fastest browser in the world in a lot of tests, and we're super-fast because our rendering engine is super-fast, the JavaScript engine is super-fast. So we're applying that same technology from engines to extensions, so that we make sure extensions are snappy, that they work and respond well to end user interactions, and it doesn't compromise the browser experience."

Next: Extensions to what extent?

This article originally appeared in Net1News.

©Copyright 2010 Ingenus, LLC.

©Copyright 2010 BetaNews, Inc.

Extensions to what extent

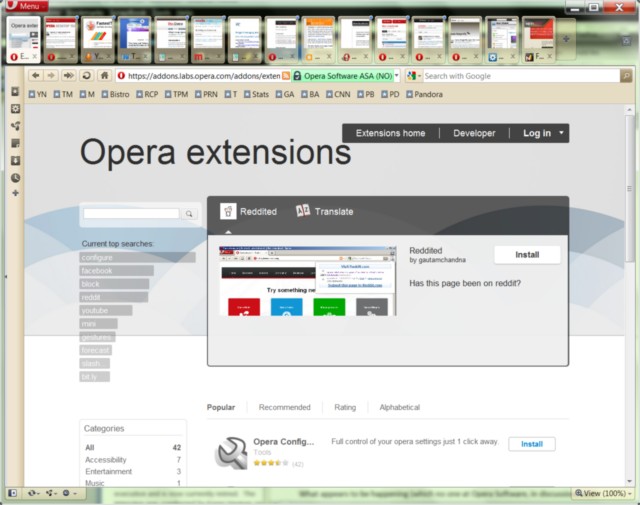

If you're wondering how an extension written purely using Web page languages like CSS can significantly change the browser, the answer is. . . they can't, at least not yet. Like a Google Chrome extension, an Opera 11 extension (at least at this stage) is essentially the next granular step in evolution from UserJS. In fact, the first few extensions released by Opera Software last week include several that don't actually change the browser itself all that much, but instead add functionality to certain pages. One very simple extension called the Opera Configurator does add an options button (with a familiar looking wrench icon) to the main toolbar just to the right of the Search box. Clicking here brings up the contents of the opera:config page, which also answers to that name from the Address box; it's already a very well-designed and useful all-in-one preferences page, but this extension places it where it belongs to begin with.

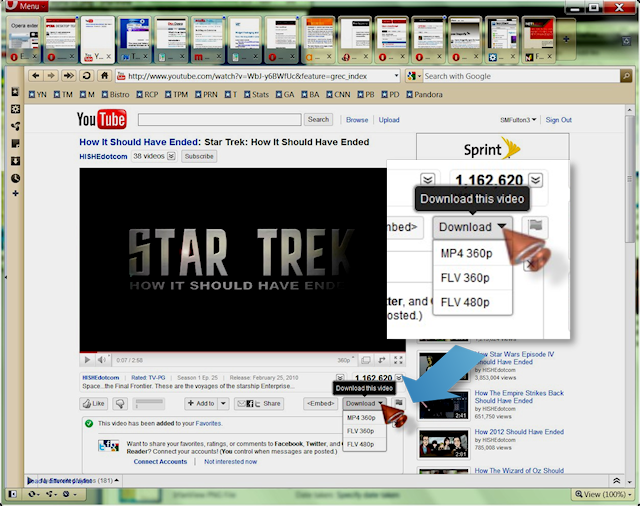

But the FastestTube extension (already well-known to Firefox users) doesn't make changes to the browser; rather, it adds a "Download" button (and a not-so-obvious one at that) to YouTube pages, letting you dump copies of Flash videos to disk for running independently or transferring to mobile devices.

Chrome extensions typically add a single button to its toolbar as a matter of course; with Opera 11, extensions don't require a button, but can add one programmatically. By including a reference to a background.js file in what's essentially a slightly modified UserJS add-on for Opera, an opera object is created. To this object, user-created JavaScript code can attach methods that create buttons and their associated pop-up menus to a safe Opera 11 toolbar. Another type of gadget which may accompany a button is a badge, whose principal job is to serve as a kind of label for the button - for example, for an e-mail-reading extension, to display the current number of unread messages.

"An extension is allowed to place one button on the Opera toolbar, to the right of the search field," reads early documentation by Opera developer David Storey. "This button can include an 18x18 pixel icon, a tooltip (displayed on hover), a status badge, and a popup overlay."

JavaScript events in the extension code can be geared to respond to user events pertaining to the button. For now, as early documentation shows, the browser can be triggered to respond to these events by bringing up a new tab (the container for a Web page) or a new window (the container for tabs).

So in sticking with the W3C's established standards for widgets, Opera 11 doesn't yet venture into the level of browser transformation that Firefox employs with XUL. This is Mozilla's XML-based implementation of a language for setting up front-ends for Firefox extensions, almost a counterpart for Microsoft's XAML. Indeed, the front end for Firefox itself is described using XUL; so Firefox extensions are enabled limited, yet direct, access to the interface elements that Mozilla originally called chrome. So Firefox extensions can change Firefox itself; for example, its All-in-One Toolbar (inspired by Opera) is made feasible by XUL, as well as Colorful Tabs, which enables multiple rows of open tabs to be color coded, either randomly or by their base URL.

It's evident, even at this early stage, that Opera 11 will not enable its extensions developers to remodel the browser that deeply. "We take this as a first step into extensions, and we're sort of opening the door a little bit, but we're just making sure that we've got the right gatekeeping in place so we don't compromise security and speed," said Teigene. "When we have an extension installed in Opera, a lot of our design choices have been to try to minimize the footprint without compromising the functionality of it."

One immediate benefit of Opera's more conservative choice may be in the security department. The context of an Opera extension doesn't really change from that of a UserJS script, which means that while there are several popular UserJS scripts that proliferate among a small community of users, the likelihood or the incentive to create malicious Opera extensions will likely be minimal.

But what about the incentive to create beneficial extensions? Almost any software around which the creation of other software centers, is a platform. Viewed from that perspective, Opera has actually been a platform for several years already. But as it moves from dipping its toes, and then its ankles, and now finally its knees into the waters of the platform development community, will Opera ever immerse itself deeply enough to enable someone out there to create the "killer app" that sells Opera as a platform?

As Opera Software's Arnstein Teigene sees it, the platform's evolution should inevitably sell Opera as the killer app: "In terms of creating the 'killer app,' Opera is known for being the most customizable browser in the world, and I think with extensions we've definitely cemented that reputation. We do have a history of making a lot of native add-ons inside our browser, because we believe that native is faster and more user-friendly. But we also believe in allowing the community to be part of this platform as well."

This article originally appeared in Net1News.

©Copyright 2010 Ingenus, LLC.

©Copyright 2010 BetaNews, Inc.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2010