By Scott M. Fulton, III, Betanews

Should the next version of HTML, the Web standard that embodies how pages are laid out and constructed, include explicit specifications for inline, 2D dynamic graphics? There's valid arguments on both sides. One side believes that the ability to plot charts and animations would have been part of the original HTML standard anyway, had the technology existed on the back end in the beginning; giving HTML 2D graphics now, they say, plugs a hole left open for too long. Another believes the HTML5 standard should simply specify an API for plug-ins, to let separate groups of engineers evolve a methodology for plotting graphics at their own pace, and on their own track.

Should the next version of HTML, the Web standard that embodies how pages are laid out and constructed, include explicit specifications for inline, 2D dynamic graphics? There's valid arguments on both sides. One side believes that the ability to plot charts and animations would have been part of the original HTML standard anyway, had the technology existed on the back end in the beginning; giving HTML 2D graphics now, they say, plugs a hole left open for too long. Another believes the HTML5 standard should simply specify an API for plug-ins, to let separate groups of engineers evolve a methodology for plotting graphics at their own pace, and on their own track.

From one angle, the debate appears as innocuous as this: Should graphics be considered within the scope of a markup language, or not? But any debate on the topic of Web standards development has never sustained continued viewing from one angle alone. From another angle entirely, one can't help but notice that the principal advocate of letting the so-called Canvas element be developed separately, is an engineer with Adobe, which has more than the average stake in the outcome of Web graphics development.

When the Adobe stakeholder appears to agree with the co-chair of the working group, who hails from Microsoft; and the author of the would-be Working Draft document has ties to Google, it's not long before someone from Opera Software, quite literally, cries "Sabotage!"

Last month, among members of the W3C's HTML5 Working Group, a dispute arose over whether the Working Group had the authority to declare the specifications for the Canvas element (not just the plug-in, but the component itself) part of HTML5. Adobe engineer Larry Masinter raised the point that he believed the decision had already been made to split Canvas 2D into its own First Public Working Draft (FPWD).

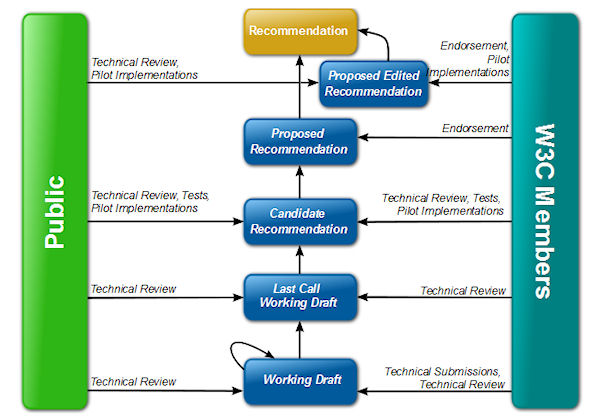

Indeed, there was evidence to back Masinter up on this point, as other W3C participants were either working under the belief that Canvas 2D was on its own track, or noting that a dispute on that issue had yet to be resolved. During a W3C presentation last month, long-time project leader Philippe Le Hégaret acknowledged that a specific difficulty remained before the Last Call Working Draft -- the next-to-last stage on the diagram he was showing the audience -- could be completed.

"If you take a specification like the HTML5 specification, it's still in the Working Draft status," reads Yahoo's official transcript of the presentation. "We still have several open issues opened against the document. In particular, several accessibility issues that need to be resolved before we can move the document to Last Call."

By "accessibility," Le Hégaret was using a keyword in the argument in favor of breaking Canvas out from HTML5: that letting a separate group handle it at its own speed, would make Canvas more accessible to its own developers.

In an interview published by the W3C just last Friday, Le Hégaret corresponded with HTML5 Working Group Co-chair Paul Cotton, who also manages Web Services Standards Strategy for Microsoft Canada. In an obviously leading question (like I've never asked a leading question myself), Le Hégaret asked Cotton to explain what HTML5 has evolved to become, in the broad sense. "I agree that many of us use the term 'HTML5' very loosely," began Cotton's response, obviously agreeing with someone in the room.

"First, I believe that most people use the term 'HTML5' to refer to the HTML5 specification currently being worked on by the HTML WG," he continued. "The HTML5 specification defines the syntax and the semantics of the elements and attributes in the HTML markup language and several of the APIs that are used to process HTML documents. Recently the HTML WG has started to break the HTML5 specification into more modular and separate Working Drafts -- e.g., HTML+RDFa, HTML Microdata, and HTML Canvas 2D Context. The HTML WG is also publishing two additional documents to aid users of HTML5: the HTML5 differences from HTML4 specification and HTML: The Markup Language which is aimed at developers that produce HTML5 output. Each of these additional Working Drafts are still part of 'HTML5' and are all on track to become separate but related W3C Recommendations or Working Group Notes. I believe that the content of these WDs taken together will define the part of 'HTML5' being worked on by the HTML WG."

That's how Microsoft's participant described the situation just last Friday. Last February 5, in the Working Group's public mailing list, Adobe's Masinter made it clear he believed Canvas 2D was being split into a separate Working Draft document, and that he disagreed with others' assessment that the WG's own director could somehow also include it concurrently within HTML5.

A diagram of the typical evolutionary process of a W3C Working Draft, from a February 2010 presentation by HTML5 Working Group member Philippe Le Hégaret.

The following Monday, it appeared as though Le Hégaret sided with the gathering consensus that Canvas is essentially already part of the understood scope of the broader document. However, he did suggest a kind of intermediate solution: the document modularization concept. "The scope of the [Working Group] charter says: 'This group will maintain and produce incremental revisions to the HTML specification,' and the deliverables indicates: 'a language evolved from HTML4 for describing the semantics of documents and applications on the World Wide Web.' I don't think it sets boundaries on what ought to be part of the HTML specification. Whether the figure, video, or data-* is inside the HTML5 specification or in an adjunct doesn't make a difference. We've been encouraged on several occasions to modularize the HTML specification itself, in fact. The Context 2D API was part of the HTML5 specification even before the creation of the charter and was accepted as such by the Working Group."

As the minutes of the public meeting of the Working Group from the following Thursday, February 11, indicate, when one of the meeting co-chairs -- Microsoft's Paul Cotton -- stated that the requested changes (the "diffs") were being worked into the Call for Consensus document -- implying that all was going swimmingly -- Adobe's Masinter interrupted. "Do I need to repeat objections?" he asked. "The co-chairs are aware of the formal objection," Cotton responded.

The other co-chair was IBM engineer and Apache contributor Sam Ruby. "It would be helpful to repeat the objection," Ruby said. "It would be helpful to people who aren't reading w3-archive e-mail," Cotton added, referring to the administrative mailing list for private issues among members -- usually points of order.

But here, Le Hégaret made a bold statement: "We won't approve the [First Public Working Drafts] until the [Formal Objection] is resolved." What formal objection? Wasn't there a dispute over whether there even was an objection? Cotton asked Masinter and Le Hégaret to forward their objections to the public list for everyone to read; they agreed.

Next: The search for a conspiracy theory...

The search for a conspiracy theory

So how deep was this problem? According to the HTML5 document's designated author, Ian Hickson, it was the standards world's equivalent of a Senate filibuster: "The latest publication of HTML5 is now blocked by Adobe, via an objection that has still not been made public (despite yesterday's promise to make it so)," Hickson wrote. He cited a source who apparently wished to remain anonymous, for reasons he said had to do with belonging to "one of the secret W3C member lists," implying that the Working Group had a public agenda and a private one. This despite the fact that the differences between Masinter's and Cotton's perception of the matter may have been trivial at best.

Later, in a blog post entitled "Sabotage!" obviously intended to raise the eyebrows of would-be news aggregators, Opera Software engineer Anne Van Kesteren essentially alleged Adobe -- the manufacturer of Flash, a proprietary graphics technology -- was blocking the forward progress of HTML5 on a technicality: "The objection to HTML Canvas 2D Context is spurious in particular since it has been part of the W3C draft of HTML5 since the very beginning," Van Kesteren wrote. "The scope question for that API has been raised two years ago and was resolved back then, involving all the layers of W3C, including its Director. That it is now decided to publish it is a separate document does not change the resolution of this decision on scope."

But while the "sabotage" story was raging, the creator of the Web himself, Tim Berners-Lee, called upon the W3C to implement an "annotation" to the Working Group charter to enable the modularity that Cotton referred to. "I agree with the WG chairs that these items -- data and Canvas -- are reasonable areas of work for the group. It is appropriate for the group to publish documents in this area. On the one hand, they elaborate areas touched on in HTML4. On the other, these elaborations are much deeper than the features of HTML4, but also they form separate subsystems, and these subsystems have strong overlaps with other design areas. It is important (a) that the design be modular; (b) that the specifications be kept modular and (c) that the communities of expertise of the respective fields (graphics and data) be involved in the design process. I am asking the domain lead to annotate the charter in place to make these points clearer to newcomers."

Calling the entire substance of the blocking/filibuster allegation "hooey" in a personal blog post two weeks ago, Larry Masinter revealed not only that he followed through with his procedural objection, but he essentially got what he wanted: a change in the charter of the Working Group so that it did encompass Canvas 2D, rather than having a charter that appeared to contradict its own work. But then Masinter's retort took on the broader, and more timeless, topic of what the devil is going on here anyway.

"Updating the charter to say these things were in scope was always a way of bringing them into scope," Masinter wrote. "That W3C wanted to save face and call it an 'annotation' and skip the normal W3C rechartering process -- well, so many exceptions were made for HTML in the first place, that's fine. What makes a 'standard' process 'open' isn't just 'everyone can read the mailing list.' Trying to follow the HTML standard requires withstanding a 'denial of service' attack; thousands of e-mails, messages, posts, edits to track every single month. No one person can really follow what's going on.

"I've worked on scores (more than 20 and probably more than 40) different working group charters," Masinter continued. "I think I really understand why working groups have charters, how the words in a charter are chosen carefully, and why it's important to keep things in scope. Is that being nit-picky? Yes, but that's what I do. And, I claim, it's what makes good standards: Follow process, pay attention to details. My perspective is that what makes a good standard is very different than what makes a good implementation guide. Many otherwise good software engineers (even those with a great deal of experience) really don't see it, since their experience and intuitions have served them well in building complex software systems, or leading open source projects."

As of now, the HTML5 Working Drafts are officially published, with Canvas 2D among a handful of specifications broken out into modular drafts of their own, as Berners-Lee advised. And that prompted a note of applause last Friday from Microsoft's Internet Explorer 9 Program Manager Adrian Bateman: "Just like good software design, loose coupling and high cohesion are good principles for defining web standards. That doesn't make them easy to apply and there is still more work to do to reduce the coupling between drafts. The group is working on improving the tools used to generate the documents to improve the cross-references, which will help towards this goal."

Bateman's comments have contributed to blog posts today pointing to "rumors" that IE9, and Microsoft in turn, would come around to supporting HTML5. This despite the fact that its own man may be to thank for getting the whole draft put together prior to Microsoft's MIX conference next week.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2010

Never mind that developers have been begging Apple to open up the API so that they don't have to get in through the back door. Never mind that tech-savvy consumers now have another reason to jailbreak their devices. Never mind that this is yet another example of near-Draconian (or maybe full-on Draconian) control over a platform that, despite its extreme popularity, remains a prime example of the risks of leaving too much control in the hands of one provider.

Never mind that developers have been begging Apple to open up the API so that they don't have to get in through the back door. Never mind that tech-savvy consumers now have another reason to jailbreak their devices. Never mind that this is yet another example of near-Draconian (or maybe full-on Draconian) control over a platform that, despite its extreme popularity, remains a prime example of the risks of leaving too much control in the hands of one provider.