By Scott M. Fulton, III, Betanews

For years, RealNetworks has wanted to produce and sell a product called RealDVD that would enable the legal owners of DVD movies to copy their content onto a hard disk drive, in order that the original discs may stay protected like archival copies. Movie studios responded in September 2008 by suing Real, alleging that its technology intentionally circumvented their copy control system -- a circumvention that violated the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act. That led to an injunction barring any sale of RealDVD, which is still in force today.

Real then responded with a countersuit, blasting the movie studios with an allegation that they were leveraging the DMCA as a platform on which to build a kind of content cartel -- a mechanism that disables viewers and the companies that sell to viewers from using DVDs in any other way besides direct viewing, that doesn't involve a licensing agreement. Last Friday, the judge in that ongoing suit ruled that Real had not proven the basis of its argument, noting that at any time, Real was free to enter into its own individual licenses for copying DVDs, and that there's nothing to stop it from doing so.

As Real stated in its defense at the time, "RealNetworks believed then, as it does now, that a consumer who had purchased, for example, an Iron Man DVD, does not need further permission from Paramount to copy that DVD onto her hard drive so as to get the benefit of additional features that can only be provided by the saving to a hard drive."

But Judge Marilyn Hall Patel ruled Friday that just because Real believed there was no need to purchase a license, did not prevent it from negotiating to purchase a license. Thus the movie studios could not have collectively prevented Real from making a copying mechanism possible, since the alternative of negotiation was there and has always been there.

"The Studios argue that any injury to Real has been caused by Real's own illegal behavior and the court's resulting injunction, rather than any anticompetitive behavior," wrote Judge Patel. "The only harm alleged by Real is the delay of its product launch... Real decided to delay the launch of the product until September 30, 2008, 'while it attempted to address the Studio Defendants' concerns regarding the product.' The product was launched on September 30, but the sale and distribution of RealDVD was enjoined days later by the court's [temporary restraining order]. The ongoing delay in marketing RealDVD results from the TRO and preliminary injunction entered by this court. Any assertion by Real that the Studios' refusal to license the copying of DVDs caused an antitrust injury apart from the delay resulting from the injunctive relief is contradicted by Real's assertions that it believed no license was necessary."

Later, Judge Patel summarizes Real's argument in an effort to demonstrate its circularity: "The court understands Real's argument, stated in its most coherent form, to run as follows: (1) there is a "cartel" agreement that is illegal under the antitrust laws and should be held unenforceable; (2) in the absence of the agreement, RealDVD's copying of CSS-encrypted DVDs would not violate the DMCA; (3) if RealDVD did not appear to violate the DMCA, it would not be subject to a preliminary injunction; (4) the illegal agreement therefore caused injury to Real by making Real's activities subject to a preliminary injunction under the DMCA; and (5) accordingly, Real has antitrust standing to challenge the 'cartel' agreement under the antitrust laws.

"Apart from the circularity of the argument, there are at least two fatal problems with Real's position," the Judge continued. "Firstly, Real's argument makes sense only if the relevant market for purposes of the antitrust analysis is restricted specifically to technologies that copy content from CSS-encrypted disks, because the alleged anticompetitive agreement does not compel any studio to distribute its content exclusively on CSS-protected DVDs. Real's product saves and manages digital copies of movies, and Real has made no allegation that individual Studios have refused to negotiate individual licenses for digital copies of their movies. Nor does Real dispute that companies such as Apple and Amazon have negotiated arrangements with various motion picture studios to distribute copyrighted content through their services. The 'cartel' alleged by Real has purportedly denied Real and consumers access to an encryption system, CSS, that protects DVDs from copying, but this has nothing to do with Real's opportunity to license the Studios' content. Real attempts to overcome this flaw in its theory by asserting that its target market is specifically the market for copying CSS-encrypted DVDs already owned by consumers. Yet this is not what Real's complaint alleges. According to the complaint, 'The relevant product market is the provision of technology that enables consumers to (a) create or otherwise obtain digital copies of movies and TV shows that they own on DVDs and (b) store and manage those copies electronically (e.g., on a hard drive) for subsequent playback.' (emphasis added). This market definition is not restricted to the market for copying CSS-encrypted DVDs."

Real had alleged that one of the purposes of the alleged cartel was to corner the market for unprotected content -- specifically, the "digital copies" included with many deluxe DVD and Blu-ray packages today. But Judge Patel concluded that the very existence of such digital copies implies that the studios were not using CSS copy protection to form a blockade through which only certain licensees may pass, as Real had also earlier alleged.

As a result, the court has dismissed RealNetworks' claims of antitrust violations on the part of the motion picture industry. The basis of the case, however -- whether Real or anyone will be able to market a product like RealDVD -- continues.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2010

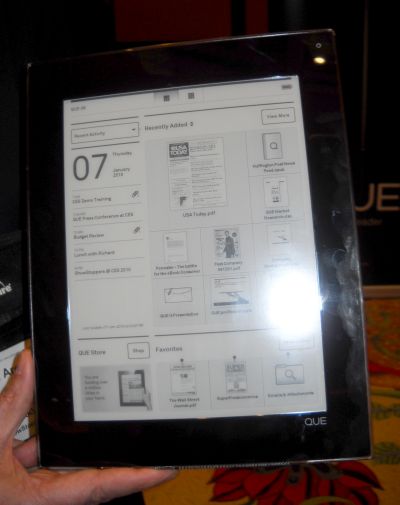

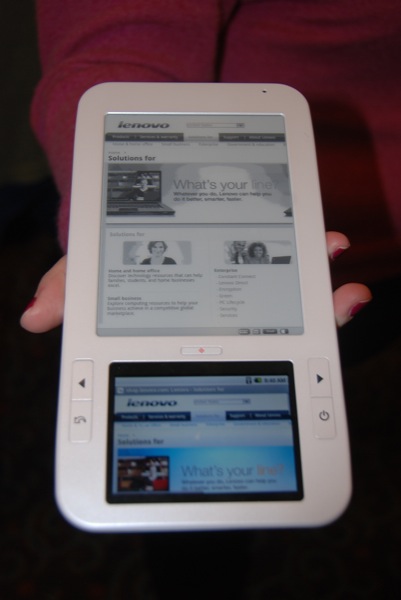

On the ARM side, Plastic Logic's entry into the suddenly crowded e-reader market carries a hefty price tag of up to around $800. But the Que uses a plastic rather than a glass screen for "unbreakability," contended Plastic Logic CEO Richard Archuleta, speaking with Betanews during the Showstoppers press event. Plastic Logic's e-reader is also specifically designed as a "business e-reader," with support for formats such as Windows PowerPoint, he elaborated.

On the ARM side, Plastic Logic's entry into the suddenly crowded e-reader market carries a hefty price tag of up to around $800. But the Que uses a plastic rather than a glass screen for "unbreakability," contended Plastic Logic CEO Richard Archuleta, speaking with Betanews during the Showstoppers press event. Plastic Logic's e-reader is also specifically designed as a "business e-reader," with support for formats such as Windows PowerPoint, he elaborated.

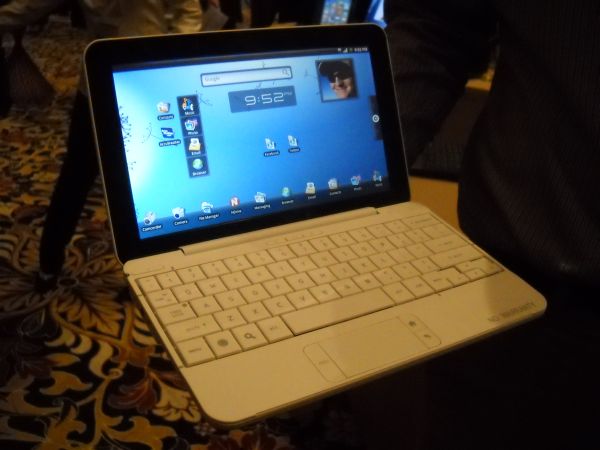

Without a doubt, Android has emerged from CES 2010 as the software platform story of the year. In a strange way, the sudden surge of activity for the platform prior to CES, and even prior to Google's Nexus One announcement the day before CES, is what substantiated the presence of Android in the public discussion this year. Up until now, Linux on the smartphone has been perceived as an "alternative" to the branded systems -- last year, Android seemed to be the culmination of something going on in the "open" space, out there somewhere, categorized under "Other."

Android is not "other" any more. It is here, and very much at the center of things.

Without a doubt, Android has emerged from CES 2010 as the software platform story of the year. In a strange way, the sudden surge of activity for the platform prior to CES, and even prior to Google's Nexus One announcement the day before CES, is what substantiated the presence of Android in the public discussion this year. Up until now, Linux on the smartphone has been perceived as an "alternative" to the branded systems -- last year, Android seemed to be the culmination of something going on in the "open" space, out there somewhere, categorized under "Other."

Android is not "other" any more. It is here, and very much at the center of things.

The biggest winner overall was Qualcomm, now not only an "inside" player in platform technology but a brand that people will discuss alongside Intel and LG. Not only did Snapdragon steal folks' attention, but Qualcomm's

The biggest winner overall was Qualcomm, now not only an "inside" player in platform technology but a brand that people will discuss alongside Intel and LG. Not only did Snapdragon steal folks' attention, but Qualcomm's