By Scott M. Fulton, III, Betanews

The problem with the release of a Transportation Security Administration security screening manual was not, as many news outlets reported yesterday, the fact that it appeared "out there on the Internet." As US Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano told reporters this morning, according to the Washington Post, the TSA manual was supposed to have been posted on the Internet -- it was part of a cache of documents intentionally posted to a government procurement Web site.

The real problem is that the portions of the PDF document that were supposed to have been redacted -- or removed from the file and replaced with blackouts -- were not actually removed. Sec. Napolitano said this morning that disciplinary action may be taken against the TSA employees responsible, and at one point implied that only one person may inevitably be to blame.

But the fact that blackouts were applied yet the underlying text remained, indicates that the eventual cause may be deeper than just personal error. Betanews tests confirm that the supposedly redacted text from the TSA screening document were merely covered up by black rectangles, not deleted. A properly redacted document must clearly show where the original text was located, so as to boldly indicate its removal. The purpose of the blackout, generally, is to leave clear evidence of deletion, and thus not give readers the impression that the removed text could have been anywhere and of any length.

Our tests using Adobe Acrobat Professional, accompanied by our research of Adobe documents, indicate that the TSA may not have been using updated software. If it had, its employees' redaction process may have been more thorough, and that the underlying sensitive text may have been properly deleted.

Acrobat Professional 8 was the first version of Adobe's software to contain its own built-in tools for true redaction. Until then, Adobe directed customers to an add-on product that is still on the market, manufactured by Appligent, called Redax. That tool generates a securely redacted PDF document as the user marks segments of the original document for redaction. Applying the changes dynamically to a duplicate ensures that none of the original text is actually deleted from its file, while simultaneously ensuring that the redacted version of the document actually does get created.

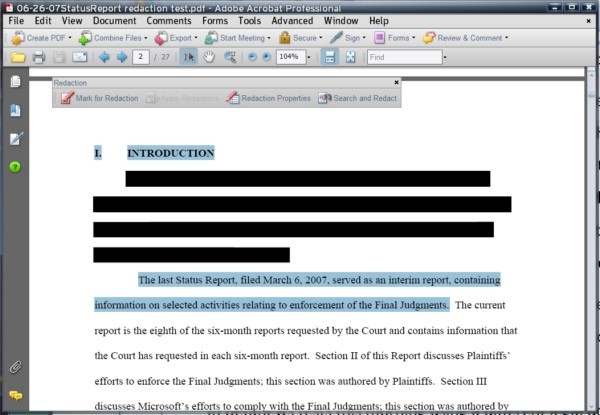

In Acrobat Professional 8 (which is not even the most recent version), the text redaction process is not straightforward or intuitive, though it is meticulous enough that it can only be done deliberately and with full awareness of the results. There is a redaction toolbar, whose principal button is called Mark for Redaction. This button changes the cursor tool into a highlighter for indicating text intended to not only be marked with blackouts, but to be removed from a copy of the file as well.

Acrobat 8 gives the user clear warnings that the redacted file should be saved as a copy. It's therefore not as thorough as the Redax tool, which maintains the redacted file as a simultaneous copy. Nevertheless, Acrobat does guide the user through the process.

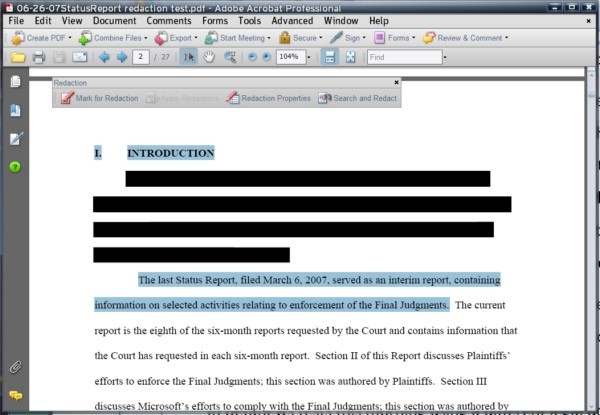

In Betanews tests using a different legal document unrelated to the TSA matter, we used the Redaction toolbar to mark a paragraph. We then clicked on Apply Redactions. As a result, using the default settings from Acrobat 8, the redacted text appeared in all black.

We then saved our redacted test document to a separate file. We then tried copying text around the redacted paragraph, and pasting it into a Notepad file to see whether the redacted text was still existent and legible, as it was in the TSA document. The redacted text was missing from the copied element, although the non-redacted text around it was properly pasted.

We also examined the saved, redacted file. PDF text isn't like HTML markup, so you can't read the main body of content just from its source material -- Adobe masks and compresses it. Still, the clearly changed portion of compressed code in the vicinity of the redacted text, coupled by the slightly smaller file size in proportion with the paragraph we redacted, indicates that the paragraph's contents did not appear in our test document -- it was gone, as it should be.

In short, had the TSA been using updated Adobe software, the security incident never would have happened.

In the TSA document, the supposedly redacted portions are masked with four-sided black rectangles with red borders, indicating that they were simply drawn as geometric objects. Prior to the release of Acrobat 8, Adobe was fully aware of customers' requests for true redaction tools.

In a December 2005 post to Adobe's own blog for legal professionals, the company's business development manager, Rick Borstein, acknowledged not only that the lack of built-in redaction was a missing feature, but also a security concern for the US government.

"A PDF distributed by the US government contained covered over text that was fully accessible," Borstein wrote. "In this case, the user authored a document in Microsoft Word and used Word's Tables and Borders toolbar to set the background color to black. Thus, black text on a black background which was not visually readable, but does not eliminate the data. When the user converted the document to PDF, a simple search of the document revealed the text."

He also related a separate incident where a user in a law office had used Acrobat to create false annotations -- notations intended for use as comments -- but positioned them over text that was not supposed to be read. "Un-redacting" the text, therefore, was as simple as turning Annotations view off.

Borstein went on to recommend that customers invest in Appligent's Redax tool. But then he offered readers an interim solution, something he felt would suffice for many users in the interim. He showed them how to draw black rectangles around text so that it appears redacted.

"There is another alternative which doesn't require any special software, but I do not recommend it unless you are *) really, really careful; *) seldom need to redact," he wrote, before demonstrating the rectangle effect. To ensure that the effect really does permanently cover up text from viewing, Borstein suggested that the resulting file be "flattened," or converted into a document with embedded TIFF images -- which is something many law offices, courts, and government agencies do today.

In a 2006 brochure on the subject of redaction (PDF available here) -- again, prior to the release of Acrobat 8 -- Adobe clearly warned its customers that customers tend to fail to properly redact sensitive material simply because they don't understand the nature of electronic documents.

"Editors may try to cover sensitive information with a colored rectangle or by highlighting text in black," reads Adobe's 2006 brochure. "While these methods work for hard copy documents, they are not appropriate for electronic documents because there are ways to extract the information from the resulting PDF document."

Acrobat is not, and never was, a word processor. The original text for documents is often created elsewhere -- in many cases, in Microsoft Word. There, users would often find their own ways to black out text in a document, making it appear to be redacted. They then operated under the mistaken assumption that Acrobat merely processed the text that users could see, when it actually absorbs all the text from the original, including that which appears obscured.

"The key to understanding how sensitive data can be embedded in a PDF document is that information hidden or covered in an electronic document, can easily be recovered," Adobe's brochure reads. "The solution is to ensure that sensitive information is not just visually hidden or made illegible, but is actually deleted from the source file."

Again, Adobe recommended Appligent's Redax tool for securely redacting text through Acrobat, especially when the source material is unavailable. Still, Adobe's warnings paint a much clearer picture of the operating conditions for any office that utilized, or continues to use, older versions of software including Adobe's. Since Acrobat is not a word processor, and since the source documents being prepared for public distribution may not necessarily be attached to those documents, a worker may not have had any actual tools for deleting the material he or she was directed to redact. Though a document can be created in Acrobat, a document whose source material comes from elsewhere, acts like a read-only copy. With modern versions of Acrobat, text from that copy may be redacted, and its underlying content deleted. But the result is not like hitting the Delete button on a word processor; truly redacted sections are clearly marked.

With older versions of Acrobat, a user may not have had many options. He could have drawn a rectangle around the blacked-out portion, but the next step would have been to flatten the file -- to make it look like something scanned from the copy machine. It may have also ballooned the byte count of the final output. What's more, the act of rendering the public portion of the text unusable, may have been a violation of policy.

All these factors should be taken into account during the government's investigation of the TSA's non-redacted document release, especially before considering the matter of who is eventually to blame.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2009

Mobile browsers have come a long way in a relatively short time. In a way, webOS, iPhone OS, and Android users have been kind of spoiled by the fast and easy-to-use browsers installed on their devices by default. For these sorts of users -- the ones who pull out their mobile phones to run a search every time someone has an unanswered question -- it's easy to forget that much of the mobile world would rather avoid opening its default mobile browser at all.

Mobile browsers have come a long way in a relatively short time. In a way, webOS, iPhone OS, and Android users have been kind of spoiled by the fast and easy-to-use browsers installed on their devices by default. For these sorts of users -- the ones who pull out their mobile phones to run a search every time someone has an unanswered question -- it's easy to forget that much of the mobile world would rather avoid opening its default mobile browser at all.