By Scott M. Fulton, III, Betanews

I know when I've hurt a man's feelings. In a segment of the technology business that has recently become fiercely competitive, it's difficult to report bad news about a team that tries very hard to build a good Web browser. It was very apparent from our interview today at PDC 2009 in Los Angeles that Microsoft Internet Explorer General Manager Dean Hachamovitch has an emotional and personal investment in the product he's building.

"If I had a script engine that was twice as fast as the one before, the Web should be twice as fast," said Hatchamovitch today. "But if JavaScript is 10 percent of my site, at most, I'll shave 5 percent off; and if the site was 1.8 seconds, yea, I'm not going to be able to tell...Yes, we understand that there's a microscope on JavaScript performance. We've made progress on JavaScript performance -- we're all in the same neighborhood now."

He was referring to the first news of development of Internet Explorer 9, which he confirmed only began weeks ago, but whose early builds -- according to both Hatchamovitch and Windows Division President Steven Sinofsky today -- were producing JavaScript performance numbers that were comparable to its competition for the first time since Mozilla released Firefox 3.5.

"That's just going to re-emphasize that it's the systems that come together. Because as all the JavaScript engines converge on their performance, people are going to notice the other 90 percent [of Web components] a lot more significantly."

Betanews' reporting on Internet Explorer in the past few months has not been kind. The October Patch Tuesday round of fixes included one for all versions of Internet Explorer that addressed a very serious, possibly exploitable issue. While we feel addressing this issue is absolutely necessary, we also noticed that applying the patch resulted in a noticeable slowdown in IE performance. At least, noticeable to us.

The most vocal reader response to our reporting could be grouped into three categories: One group vocalized that it did not care about Internet Explorer performance as a factor in computing, since it's mainly a way to read news articles anyway, and voiced their opinion that we shouldn't care either. Another group of readers took Microsoft to task for, in their opinion, not caring about IE performance, but added that it shouldn't be expected to care because nobody else does (or at least, nobody of importance) and that we should drop the subject for that reason. A third group applauded our efforts to, in their opinion, expose Microsoft for not caring about browser performance.

None of these are groups that anyone at Microsoft would want to appear publicly aligned with. So perhaps part of Dean Hachamovitch was interested in speaking with me today, and another part -- for absolutely understandable reasons -- was dreading the thought.

But bravely, he made his company's case, a valiant effort to split the difference: JavaScript isn't the Web, he asserted, but just one of many subsystems. A multitude of other factors will contribute to users' decisions. "There's performance, there's interoperable standards, and there's graphics," said Hatchamovitch. Each component strikes a different chord with different groups of users, he said. Since the Day 2 keynote's conclusion, he and his press handler had opportunities to ask individuals what they thought of the presentation -- or more specifically, what did they remember from it?

"I asked some folks what they heard, and some just said, 'Yea, you guys are doing a lot of compliance and interop.' 'Did you hear anything else?' 'No, not really.' Talked to someone else, 'So what did you hear?' 'You guys are doing some stuff around making the script engine faster.' 'Huh. Anything else?' 'No, not really.' So what I'm finding is that this is the classic game of Telephone."

What resonates with various attendees is essentially aligned with what they want to hear, Hatchamovitch went on...perhaps to illustrate the point that when he asked me the very same question at the start of our interview, I dove right into the performance aspect.

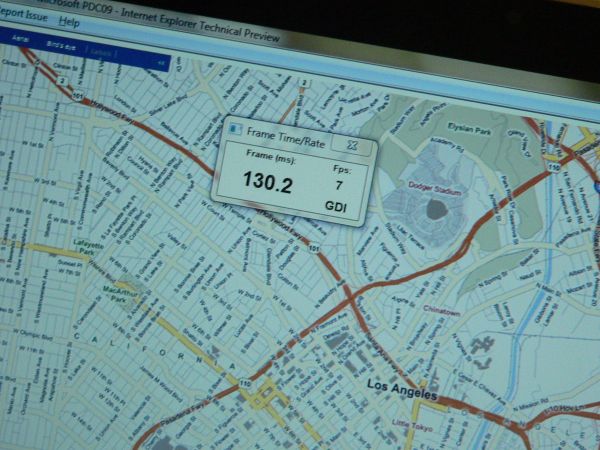

Rendering is another critical aspect, and we saw demonstrations of the changes IE9 will make in the rendering department. Specifically, the next edition of Microsoft's browser will move away from GDI, the graphics library favored by Windows during the late 1980s, and toward the new Direct2D library which takes fuller advantages of the capabilities of the underlying hardware, including the GPU. In response to my request for a video that showed this performance, Microsoft asked us to include in our story the video you see embedded above, which is as close as the Web can come to approximating the speed and fluidity improvements attainable through Direct2D.

There is absolutely no question that, if IE9's rendering improvements were to simply stay on the same level as they appear from these early demonstrations, through to the end of the product's development, the result will be a perceptible qualitative difference that could be the deciding factor in whether Firefox or Chrome or Safari users switch back to IE -- as important a factor as computational performance.

Hachamovitch showed us up close the map rendering demonstration seen from a distance during the Day 2 keynote. Shifting the same road map across the screen on a small Dell XPS laptop produced typical, perceptible jitters using IE8's GDI graphics methodology, compared to a smooth, even flow using IE9's Direct2D.

Hachamovitch showed us up close the map rendering demonstration seen from a distance during the Day 2 keynote. Shifting the same road map across the screen on a small Dell XPS laptop produced typical, perceptible jitters using IE8's GDI graphics methodology, compared to a smooth, even flow using IE9's Direct2D.

Some folks were confused by the meaning of the number in the demo, and why the slower, jittery-er graphic produced the higher value. This represented the number of milliseconds between frames -- a number that plummeted from 130.2 ms as in this photo, or even much higher on occasion, to as low as 8 ms for Direct2D. Actual frames per second rises from around 7 (or lower) for GDI, to about 60 for Direct2D on the same machine.

"Now, that kind of difference -- somebody said, 'Oh, it's like game-level animation!' Yea, you can call it like it's a Pixar movie or an Xbox game. But then they said, 'But what does that have to do with the Web?' It has everything to do with the Web. When you're using Web mail or this mapping site, or you're previewing photos -- imagine going to a photo site, and you want to have 1,000 thumbnails up on the screen. Now we're using the graphics card, so you're not waiting on every piece of graphics that way. That's a huge gain for performance, that's a huge gain for developers because they can use all their old patterns -- they didn't have to rewrite their sites."

So graphics does strike the performance chord with users and developers after all.

During the Day 2 keynote, Sinofsky said the IE9 team has been working for all of three weeks, and we were skeptical. Didn't IE9 development really start after IE8 was released to general availability in March? What was going on all these months?

"There's a lot of work that went into IE8 for sure," Hachamovitch responded. "But realize, on March 19 we released IE8 in a few dozen languages. After March 19, we had several waves of languages for IE8 to get out, because it's worldwide. There's more than a few dozen languages of IE8. Then we had to finish Windows 7, and all the languages of Windows 7. So we're three weeks past the general availability of Windows 7. In some ways, we've all been on call, ready, working through...well, several Patch Tuesdays since March 19."

As Microsoft tries for a valiant comeback attempt for IE in the realm of qualitative measures, expect the company to demonstrate any number of various other aspects where the browser makes gains, and say this, too, is the Web.

And if those gains in one or two departments aren't as significant, expect the message to be, "But that's not all of the Web."

We've asked Dean Hatchamovitch to join us in responding to your comments to this article.

Next: A word about Dean's comments about our performance measurements...

A word about Dean's comments about our performance measurements

It is no secret to the dozens of you who have followed my work over the past few decades that I am a speed fanatic. I give a damn about the performance of my automobile, my coffee maker, my wristwatch, and my Web browser, and my wife knows it doesn't stop there. It might have something to do with why I edit a publication called Betanews.

The other reason I care is that I'm in the business of improvement, and you can't improve until you're ready to accept your own shortcomings. That goes for myself as well as everyone else. It is never fun to be on the losing side of a fair and competitive battle. It may even seem unfair when the reasons have to do with a legitimate effort to address a serious concern.

But as a high school journalism teacher I knew used to tell her students in the sports department covering one of the worst teams ever to take the field, if you can't do the simplest job in the world -- reporting the score -- then you shouldn't be a journalist but a cheerleader. Your heart may want you to change the score; but if you then do it, you've lost more than a game.

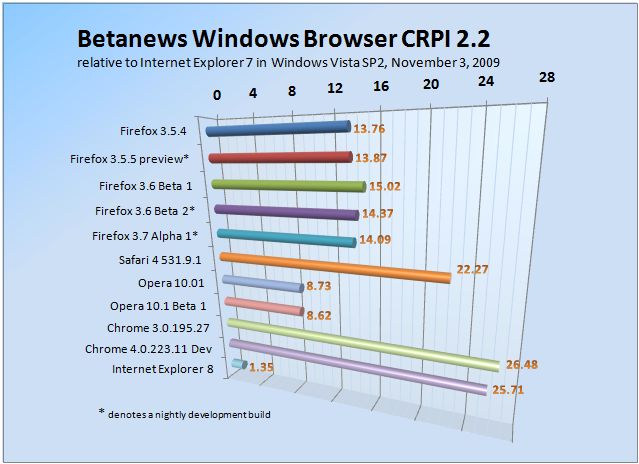

Click here for a comprehensive explanation of the Betanews CRPI index version 2.2.

Dean Hachamovitch raised a few concerns about Betanews' testing methodology, and I think they're fair concerns that are worth discussing. First, he contended that it may be confusing to him and others, for us to use Internet Explorer 7 on Windows Vista as a relativity index. I told him I did not want to do as some readers suggested I do -- use IE8 as the index browser -- because that would be unfair to IE8, disabling its ability to be measured for performance at all. I also could not use any older series of browsers (for example, IE6 or Firefox 2) because they could not even run the tests in our performance battery. I know, I've tried.

He also suggested something else: that we go back to using clean installs of operating systems on virtual machines for our test systems, so long as those VMs were running on the same hardware. I explained to him why I changed to testing on physical platforms, mainly in response to reader requests. But I also explained that during our test of IE8 performance after the October Patch Tuesday fix, to validate the numbers I was seeing, I uninstalled the patch and tested again, and reinstalled it and tested again, to verify the values -- they were spot on after the validation.

Hatchamovitch winced at this. He said that by uninstalling and reapplying the patch, I may have reduced the "signal-to-noise ratio," to use his phrase, for IE7 and IE8 on Vista. In other words, I may have polluted the platform and hindered performance. The test results did not suggest that; but my methodology, he argued, could still produce doubt as to the authenticity of my results. This is a fair argument which I will put to the test myself.

Hatchamovitch also suggested we introduce the factor of variability into the test, a plus-or-minus factor, which is often seen in many other scientific measurements of performance. Of course, that's not a bad idea either; on the other hand, I only want to report numbers that make sense to readers. If I'm "fuzzifying" the meaning of a result, I may not be giving readers data that they can use. It would be like putting a plus-or-minus estimate on the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

I stand behind my current methodology, but as you've already seen, I'm open to suggestions for improvement, and I have made improvements based on suggestions. But as I told BASIC interpreter vendors during the 1980s, who for years had seen their performance numbers in my tests slammed again and again and again by Microsoft -- which dominated the interpreter market for as long as it was important -- winning is not a relative state. Ask anyone who's improved and come back to win the next round.

The moment IE9 marks a comeback for Microsoft's Web browser in performance, you'll read about it here. Yes, performance isn't the entire Web just as the drivetrain isn't the entire car. Maybe you don't think much about the drivetrain every day, but that doesn't mean it doesn't exist. Just try riding in a car without one.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2009