By Scott M. Fulton, III, Betanews

The problem is not so much Google itself. The problem is with the self-absorbed-yet-insecure nature of a plurality of industries, media being just one among them, whose collective inability to plan how they would conduct business in the era of digital multimedia communication, led them to essentially give up, give in, and let Google build it all for them.

Conducting business is all about staying visible, not just in front of the public's eyes but in its conscience as well. It's why Coca-Cola continues to advertise itself even though folks are likely to go on drinking it anyway (there's a great gag about this fact in Ricky Gervais' latest film, The Invention of Lying). At a time during the evolution of the Internet when businesses were busy trying to construct analogs for physical business entities -- such as online shopping malls with 3D virtual escalators, online business directories that were alphabetized, and "portals" that sought to become the world's centers for particular industries, such as dog grooming -- along came an Occam's Razor that appeared to make everything much simpler: It was the idea that visibility, that critical ingredient of all business relationships, can be engineered.

This, actually, is the same principle that has driven the audience transitions between major media since the Civil War, only this time it was somewhat less deliberate. The move to radio as a news source came with the urgency of World War II; but the establishment of radio's infrastructure came two decades earlier, when major corporations realized the potential value of the commodity of capturing an audience's attention for a period of time. The transition to television as a news source was complete after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, but the establishment of television's infrastructure came three decades earlier, with the lofty, humanistic, and utopian pronouncements of men like David Sarnoff, whose goal was no less than the remodeling of the human species:

"It is with a feeling of humbleness that I come to this moment of announcing the birth of a new art so important in its implication that it is bound to affect all society," Sarnoff told the New York World's Fair in 1939. "It is an art which shines like a torch of hope in the troubled world. It is a creative force which we must learn to utilize for the benefit of all mankind. This miracle of engineering skill which one day will bring the world to the home also brings a new American industry to serve man's material welfare."

The move to the Internet as a news source is ongoing -- by any measure, a process still under construction. And yet the infrastructure, the underlying mechanism of digital transactions upon which this migration should depend, is not entirely in place to this day.

It is into this void of indecision that Google enters the picture, sounding much less like David Sarnoff than Mister Rogers, boasting no ideology or philosophy whatsoever besides the promise of a really super day. It fulfills the role of father figure that the Internet -- as a collection of semi-cooperative academic institutions, a handful of directionless private companies, and the US Dept. of Defense -- could not conjure for itself. And for the general viewing audience -- especially those veterans out there who were expecting the NBC chimes or the Peacock or something to tell them who's responsible for all this -- Google provides them with a public face.

It is into this void of indecision that Google enters the picture, sounding much less like David Sarnoff than Mister Rogers, boasting no ideology or philosophy whatsoever besides the promise of a really super day. It fulfills the role of father figure that the Internet -- as a collection of semi-cooperative academic institutions, a handful of directionless private companies, and the US Dept. of Defense -- could not conjure for itself. And for the general viewing audience -- especially those veterans out there who were expecting the NBC chimes or the Peacock or something to tell them who's responsible for all this -- Google provides them with a public face.

Ask folks on the street -- as a Google employee did once -- and you'll be told by someone, at some point, that the Internet is Google. And before you dismiss their responses as amateurish, realize that you'll get the same response from marketing consultants: "Google is the Internet in your customers' minds. If you are not ranked in the top ten, your company simply does not exist!"

Google's is a formula which, at its roots, is based on mathematical fairness. The value of a keyword, for example, is based on what businesses are bidding to appear next to that keyword, but evened out so that every business is eventually entitled to its share. Whether an article appears in the Google News feed depends on how often the context of that article or its headline appears to be covered by everyone else, and everyone's visibility in that context is evened out so that every publication is eventually entitled to its share.

It is the institution of a market economy based around nebulous concepts rather than institutions, and its inherent incompatibility with the economy of the real world is something we are only now discovering.

Now we have found ourselves in the midst of an ideological discussion that few had expected, especially given Google's unpretentious and almost shy façade: Is Google entitled to speak on behalf of all the literary creators whose voices have been silenced by neglect and inattention? And if it is, then who controls the relative visibility of literary works by F. Scott Fitzgerald and by Jane Doe when they're all available on a level playing field? If YouTube truly should become the clearinghouse for all media, then what assurance can a company obtain -- or purchase -- that a show it produces will gain more visibility than some guy's video of his cat dancing on a piano keyboard?

As we discovered last month, Google is already planning a micropayment system for handling the transactions behind the distribution of all forms of paid media -- it's not waiting for anyone's permission or blessing or even funding. And as Google told the Newspaper Publishing Association, if profiting from the distribution of media means taking over the job of publishing it...it's more than happy to oblige: "Software and support services are typically provided at no charge. Google will be happy to host content and supply the bandwidth necessary to serve content. There may be a charge for additional professional services, depending on the extent of the support necessary and the volume of views anticipated. Current models on revenue sharing for the selling of content typically involve a percentage of each sale to Google in order to cover maintenance, bandwidth, processing charges, and profit margin."

Or, to paraphrase the Coke ad from Gervais' film -- created prior to the invention of the lie -- we'll always be here anyway, and we're sure you use Google all the time along with everyone else, so we'll take care of things for you, and you just go on doing what you're doing and we'll do the same.

Perhaps the most poignant symbol to date of the weight of Google-driven visibility as a true commodity came yesterday: Shares of the UK-based advertising firm Media Corp. surged to more than triple their value from last month, after having announced that whatever strange "penalty" Google seemed to impose upon it that weighed down its search rankings, appeared to have been lifted. The firm effectively resells high placement in Google's indexes, most notably to online gambling sites whose visibility depends on how Google responds to guys typing "poker" into the query box.

It's as if the firm had announced to the world, "We're back in the Top Ten...We exist again!" And the value of that announcement actually translates into stock value. Let me say that more directly: Investors are actively trading securities based on a company's placement in Google's search results.

At this point, there's not much time or room left for complaint. Just about anyone who sounds a warning whistle is drowned out by the cacophony of his own irony, as was the case after AT&T warned the FCC that Google was plotting to devise a telecommunications monopoly for itself.

I'm not certain we as a society have completely realized the full extent of what we are willing to consign to Google, with respect to the determination of what is of value to us and what is not. It cannot possibly amount to the wholesale of the global economy, bundled with the system of human values and ideals, to Google's cloud -- certainly one private business wouldn't handle the weight of it all. But just the thought of how many businesses and even countries are willing to entertain the idea illuminates the gulf that separates the era of David Sarnoff and today.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2009

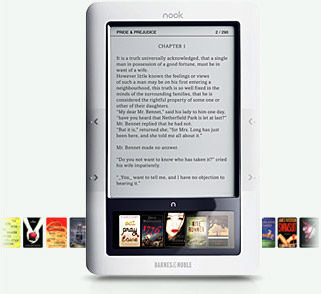

Bookseller Barnes & Noble has finally unveiled its e-book reader, which many have already slated to be the Amazon Kindle's biggest competition yet. Called the nook, Barnes & Noble's $259 e-reader includes a full-color touch panel interface in addition to its 6" e-ink display, and is the first e-reader to run on Google's Android Operating system.

Bookseller Barnes & Noble has finally unveiled its e-book reader, which many have already slated to be the Amazon Kindle's biggest competition yet. Called the nook, Barnes & Noble's $259 e-reader includes a full-color touch panel interface in addition to its 6" e-ink display, and is the first e-reader to run on Google's Android Operating system.

Continuing Apple's incremental shift away from button-based interfaces and toward multi-touch everything, Cupertino today unveiled the

Continuing Apple's incremental shift away from button-based interfaces and toward multi-touch everything, Cupertino today unveiled the  It is into this void of indecision that Google enters the picture, sounding much less like David Sarnoff than Mister Rogers, boasting no ideology or philosophy whatsoever besides the promise of a really super day. It fulfills the role of father figure that the Internet -- as a collection of semi-cooperative academic institutions, a handful of directionless private companies, and the US Dept. of Defense -- could not conjure for itself. And for the general viewing audience -- especially those veterans out there who were expecting the NBC chimes or the Peacock or something to tell them who's responsible for all this -- Google provides them with a public face.

It is into this void of indecision that Google enters the picture, sounding much less like David Sarnoff than Mister Rogers, boasting no ideology or philosophy whatsoever besides the promise of a really super day. It fulfills the role of father figure that the Internet -- as a collection of semi-cooperative academic institutions, a handful of directionless private companies, and the US Dept. of Defense -- could not conjure for itself. And for the general viewing audience -- especially those veterans out there who were expecting the NBC chimes or the Peacock or something to tell them who's responsible for all this -- Google provides them with a public face.