In March a new exhibition opened at the US National Archives in Washington DC. On display you could find, among other things, Adolf Hitler’s marriage certificate, witnessed by Goebbels, a greeting card from Saddam Hussein to George Bush, and a patent application from Michael Jackson for floor-lock shoes that allow the wearer to lean forward without falling over.

The exhibition called ‘Making Their Mark’ aimed to show how the story of the world can be told through signatures. In the months leading up to the opening, while the US archivists were busy trawling through the millions of documents available to them, a very different look at signatures was taking place across the Atlantic.

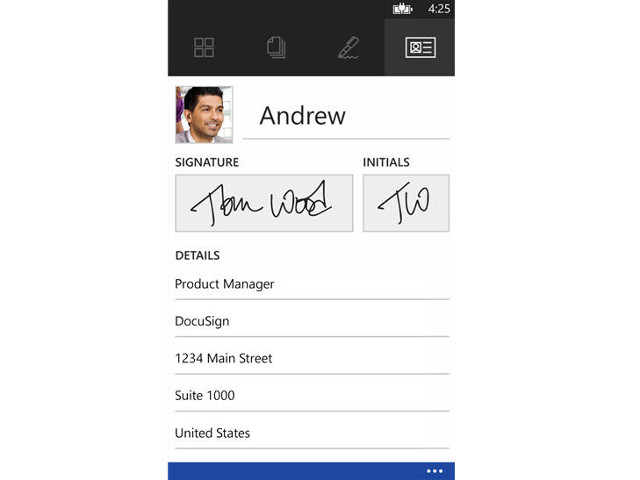

The European Union’s new directive on electronic identification and trust services (eIDAS) was in the final stages of approval, with the goal of removing the final obstacles to integrated cross-border adoption of digital identification and transactions.

By July the legislation had been approved by the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers. On 14 October it was presented to the world.

European legislation on the use of electronic signatures has been around since 1999. However, it failed to appreciate that electronic signatures don’t exist in isolation, but as part of a transaction of some sort, and therefore require consistent and uniform implementation in order to work.

Member states were able to interpret and apply the directive differently. This meant that firms had to deal with a highly complex and uncertain landscape. The directive also failed to address areas such as universal trust and authentication standards that are essential for secure and reliable electronic transactions.

As a result, many European firms found themselves trying to transform into agile, digital businesses while caught in a dependency on handwritten signatures.

Global information industry association AIIM recently discovered that, worldwide, around half of organizations print documents just to get a legally enforceable signature.

In the UK, this figure rises to 84 percent, with more than a quarter of firms (rising to 31 percent of enterprises) adding an additional day to a process just to allow for signature collection time.

Information management processes have been rendered chaotic. Half (49 percent) of the companies approached by AIIM admitted they had printed and signed documents only to scan them back in to their DM/ECM system. A third confessed that they had run off at least three additional copies of each document in order to collect all the signatures required.

Anything that can remove or reduce such inefficiencies and release information management teams to add value and insight across the business must be welcome and is certainly long overdue.

The new regulation aims to achieve this for European firms. It establishes, among other things, a uniform legal framework for electronic signatures, seals and time stamps that guarantees authenticity and origin to prevent tampering, as well as registered delivery services.

These will validate the source and integrity of electronic documents and the digital signatures they carry, paving the way for secure and trustworthy cross-border electronic transactions, applications and the delivery of public services.

The EU estimates that one billion advanced electronic signatures are already made across Europe every day and the new legislation is likely to accelerate this still further.

However, being able to accommodate signed electronic documents is just part of the story.

Companies still need to address the challenge of the paper they already hold. Not to mention all the paper that continues to arrive. Good information governance should cover scanning, storage, security, management, access, archiving and secure disposal.

There is one further perspective. Signatures are not just administrative, they are symbolic. From birth and marriage certificates to Wills and Testaments, a handwritten signature is our way of saying that something matters: I announce, I agree, I approve, I commit.

Fortunately e-signatures and handwritten ones are not mutually exclusive. A historic international treaty is not the same as a five-page loan application form. Some things are just meant to be hand-signed, and preserved on paper.

After all, who’d want to visit a museum to look at an exhibition of emails?

Charlotte Marshall is managing director of Iron Mountain in the UK, Ireland and Norway.

Published under license from ITProPortal.com, a Net Communities Ltd Publication. All rights reserved.