The headline really should be "What Windows 8 and Windows on ARM mean to Microsoft and to you" but that didn't ring right to my ears. But it more aptly describes the train of this analysis.

Simply stated: Windows 8 is the riskiest release ever. Microsoft execs say they are "re-imagining" Windows. Believe them. But it's much more: Reinvention. If successful, Microsoft will be a very different company in five years, and that's as much about the future stock price and company valuation as market position and products. All depends on the risks delivering rewards.

Windows 8 and Windows on ARM are nothing short of re-architecting Microsoft's flagship operating system from kernel to desktop. The Redmond, Wash.-based company will ask much of customers, developers, OEMs and other partners during this difficult transition, and it will be hard on everyone. But the time is now, or never. If Microsoft fails to take the risks now, Windows' luminescence will diminish in a half decade (or even less).

Microsoft needed to make these changes in the mid Noughties, and had it done so Apple likely would not be as successful with iOS devices. But Windows Vista and US antitrust oversight set back the timetable.

Undoing Antitrust Travails

Federal prosecutors, and their attorneys general partners, filed the US antitrust case in May 1998 to prevent Microsoft from stifling innovation in the tech industry. However, government oversight failed to quash the companies' twin monopolies -- Office and Windows. The case accomplished something else: Windows innovation stagnated during the last decade, as Microsoft backed off the so-called middleware categories covered by the consent decree/final judgement and withheld integrating new technologies into the operating system that should have kept the platform vital and created more opportunities for third-party developers.

The Windows 8 and Windows on ARM risks simply would be impossible if Microsoft was still under US antitrust oversight. That ended in May 2011 and almost immediately the winds of change rushed from Washington State. Clearly the company had long planned to bundle more applications and services into Windows and to make demands of software developers and hardware partners realistically impossible before.

For example, trustbusters claimed that Microsoft's efforts to offer a more unified Windows user experience across PCs was anticompetitive. As such, the company gave up control of the Windows start screen and desktop icons and hid access to some OS features, among other concessions. Repeated: Many of the risks Microsoft is taking with Windows 8 and Windows on ARM would be next to impossible under antitrust oversight.

Take Windows Store, for example. For security reasons, among others, Microsoft will largely limit software sales and distribution to the built-in Windows Store. Microsoft competitors could have cried antitrust, anticompetitive foul to government officials a year ago. Now Microsoft is freer to offer a mechanism that eventually will benefit developers (easier sales distribution, less piracy) and better protect Windows users from malware.

As Microsoft's future Windows strategy unfolds, it's hard to see where there wouldn't be trouble if antitrust oversight continued. Microsoft is dictating third-party software and hardware product design in ways not seen in more than a decade. But there's more to it: Microsoft is suddenly empowered to take competitive risks that could doom Windows if they fail.

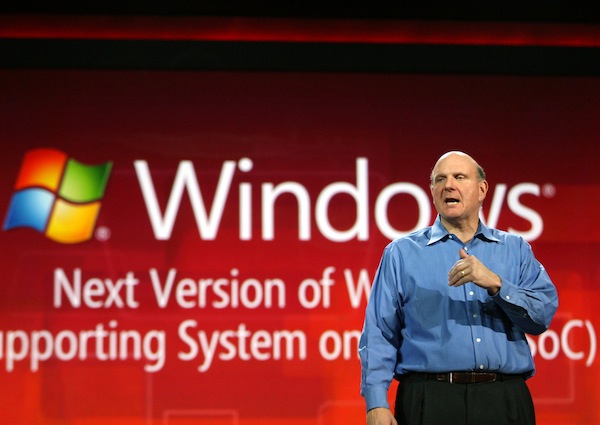

I can't emphasize how different things are now. Microsoft is itself undergoing a slow but steady process of re-imagining, of reinvention. The company long known for being risk adverse is today taking risks unfathomable five years ago. In December 2009, I called Microsoft's first decade of the new century one of "shattered dreams". A year ago, I highlighted how Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer finally had consolidated his leadership in the post-Bill Gates era. If given continued chance, Ballmer may yet redeem himself and Microsoft for this decade and the next.

Redemption Tale

One of the most prevalent themes in American cinema is redemption -- Jimmy to Stewart as George Bailey, Robert Redford as Roy Hobbs, Clint Eastwood as Frank Horrigan, Russell Crowe as James J. Braddock, Paul Newman as Frank Galvin and many, many more.

We love our heroes fallen and restored.

Steve Jobs' second coming at Apple is one of the best, real-life redemption tales of the computing age. Apple was months from bankruptcy when he returned to the company in late 1996 and became interim CEO in mid 1997. In the 2011 quarter Jobs died, Apple reported $13 billion in income, and the iPhone alone generated more revenue than all of Microsoft. It's a helluva a redemption story and one few writers could have scripted as fiction.

Ballmer's redemption story, and that for Microsoft, unfolds right now. It's a story in progress that shares similarities to Apple's. In 2001, during economic crisis, Apple made four strategic investments that are core foundation of its current success -- in order: iTunes, Mac OS X, Apple Store and iPod. On the software side, everything depends on Mac OS X (from which iOS derives) and it was a tough transition executed at a seemingly bad time.

Apple reinvented Mac OS in early 2001, with new architecture and user interface. Timing was hugely risky. Microsoft owned the PC operating system market and prepared to release Windows XP (in October). So just as the majority of developers prepped for the new Windows, Apple asked them to adopt new development tools, port older Mac OS apps and code native software. Apple couldn't get developers' attention, with major partners. Adobe and Quark among them, taking years to fully support OS X. Strangely, Microsoft supported Apple's new operating system first among the big Mac developers with new version of Office in autumn 2001.

Microsoft's situation is strangely similar today. The PC era is waning, as smaller, more mobile computing devices increase in popularity. There Apple has had huge success with iOS devices, which are pulling away sales from Windows PCs. Just in the last quarter, Apple shipped 37 million iPhones (generating more than $24 billion in revenue) -- 55 million iPads since the tablet's launch nearly two years ago. During a critical transition, when non-PC devices slop up Windows sales, Microsoft is re-architecting the operating system.

To support the new architecture, Microsoft will demand much from customers, developers and other partners -- particularly Windows on ARM. Microsoft's long-standing development priority has been this: Provide existing users backwards compatibility. Problem: The priority hampers new OS development and adoption of newer Windows editions. The company isn't fully abandoning this philosophy, but absolutely diminishing its role. Windows 8 will provide a lifeline to existing apps and the desktop motif, but the new Metro UI is priority, as are apps written for it, their distribution (through the Windows Store) and emphasis on developers writing for native code.

Windows on ARM leaps ahead, leaving little legacy behind. System-on-a-chip fundamentally changes how everyone -- customers, developers and other partners -- relate to Windows. More significantly, Microsoft is taking control over the Windows development and user experiences in a way not seen before 2000, when US District Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ordered the company's breakup (an order later overturned by an appellate court).

Time is Now, or Never

From the perspective of non-PC competition -- mobile devices connected to the cloud -- Microsoft's timing is seemingly disastrous. The company and its partners are sure to lose sales during the transition. However, from another perspective, timing couldn't be better. Businesses remain Microsoft's core market and most will have finished or be close to completing migrations from XP to Windows 7. So the majority of customers will have recently upgraded. If Microsoft is going to "re-imagine" Windows, a time when core customers are least likely to upgrade is opportune. Windows 8 and, more importantly, Windows on ARM are about preparing the ecosystem of customers, developers and others for Windows 9.

If the strategy works -- and that includes unification of the user interface across devices (ideally the codebase, too) -- Windows will be a different, more flexible, more (cloud) connected operating system by the time v8's first service pack releases than it is today; and beyond. Like Apple laid a difficult new OS foundation with Mac OS X, Microsoft is on track to do something similar, actually much better, today. Because so far, Microsoft is executing the early phases much better than Apple did more than a decade ago.

During his final Consumer Electronics Show keynote, Ballmer proclaimed: "There's nothing more important at Microsoft than Windows". Believe it, despite holiday quarter 2011 doldrums, when the division's revenue fell by 6 percent year of year and profits by 11 percent.

If Microsoft's Windows re-imagining strategy works, in a few years the stock price, which has struggled to top $30 for about 12 years, could dramatically change. Apple is example again. (Disclosure: I do not invest in Apple, Microsoft or any other company -- to avoid conflict of interest.)

On the eve of Macworld in January 2003, with Apple shares at $14.85, analyst Michael Hillmeyer reinstated Apple coverage with "sell." Hillmeyer wrote in a note to investors: "Although Apple makes great products, in our view the new product pipeline looks skimpy and we expect continued market share losses. A product differentiation strategy is difficult in a business increasingly commoditizing."

In nine years, Apple's fortune dramatically changed. There is the aforementioned blow-away fourth quarter. Then there are the shares. Apple reached a new 52-week high on Friday, $497.62. It's not difficult math to see the difference from $14.85.

There's no reason why if Microsoft's Windows risks deliver rewards, the share price can't dramatically rise by the Windows 9's release. But that's a redemption story not yet written. Is Ballmer now on the CEO's version of the "Hero's Journey"? We shall see.

This week has seen an impressive number of releases, so many that you may have missed one or two. In this roundup we’ve collected together some of the highlights starting with a selection of mobile app.

This week has seen an impressive number of releases, so many that you may have missed one or two. In this roundup we’ve collected together some of the highlights starting with a selection of mobile app.