I joined the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) in April 2001 and left the company in December 2010. During that time I was involved in security and privacy at Microsoft, culminating in my role handling worldwide crisis communications for security and privacy incidents. I am one of a handful of people who knows what the security world was like at Microsoft before Chairman Bill Gates' Trustworthy Computing memo on Jan. 15, 2002. I was also part of the growth and transformation that memo brought about over the years.

I joined the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) in April 2001 and left the company in December 2010. During that time I was involved in security and privacy at Microsoft, culminating in my role handling worldwide crisis communications for security and privacy incidents. I am one of a handful of people who knows what the security world was like at Microsoft before Chairman Bill Gates' Trustworthy Computing memo on Jan. 15, 2002. I was also part of the growth and transformation that memo brought about over the years.

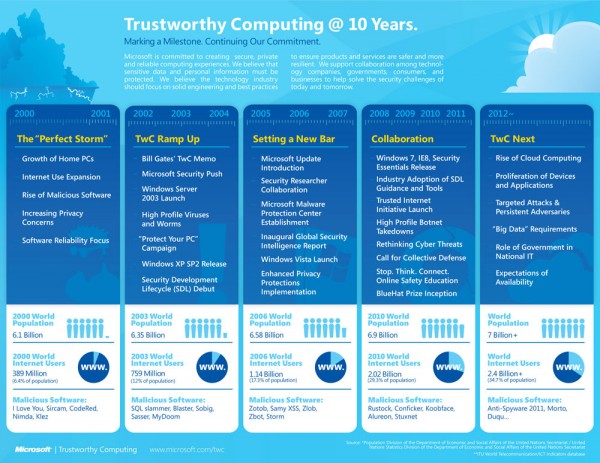

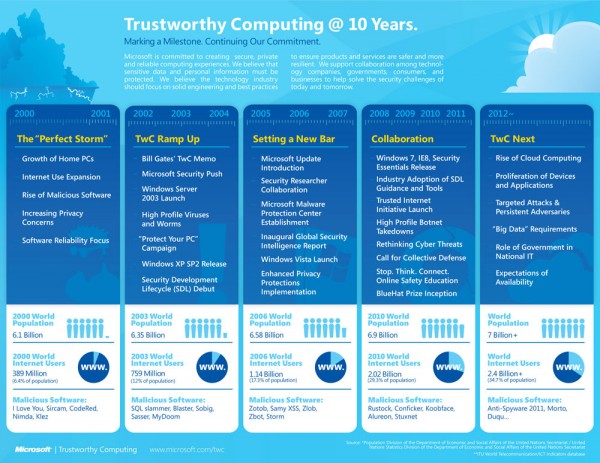

As Microsoft marks the tenth year anniversary of that memo, it seems a good time to share a former insider’s view of what it really meant and accomplished. As well, I'll share thoughts on why, in the next 10 years, it’s critical that other technology companies follow Gates’ lead.

Before: Security as Low Priority

My friend and colleague, Michael Howard, has given a view of what the world was like in 2001 - 2002 over in the Secure Windows Initiative (SWI) group. Michael was actually one of the people that interviewed me: I remember sitting with him in the Building 40 cafeteria as he asked me why I wanted to take on a job this hard. At that time, security response was such a low priority that the MSRC was part of the Windows Server marketing organization.

However, the Windows Server marketing group saw the value of fixing reported vulnerabilities in their products when no one else at Microsoft did. For the greater good of the company, they agreed to have the MSRC handle vulnerabilities in all Microsoft products (a very rare gesture back in those days).

That underscored the reality that getting vulnerabilities fixed at Microsoft back then could be a tough challenge. Resistance was so stiff sometimes that we had a list among ourselves of regular justifications we would hear for not fixing issues ("No one’s found it so far, no one’s going to find it", "It's just a theoretical issue"). One of the things that Michael warned me about that made the job so hard was the resistance from product groups within Microsoft. Sometimes we in the MSRC would find ourselves more in alignment with outside researchers than our ostensible colleagues in other groups because of it.

It’s well known how 2001 was a hard security year for Microsoft. The Code Red and NIMDA worms pushed us in the MSRC to the breaking point. Those crises showed that the resourcing and prioritization that the company was giving to security simply didn’t match emerging threats.

Windows XP had launched in the fall of 2001 and the vulnerability reports quickly followed with a critical, wormable vulnerability reported by eEye Digital Security within weeks (which was fixed just before Christmas as MS01-059). As the new year rolled around, we were truly concerned that an overwhelming tidal wave of vulnerabilities and attacks lay ahead. We were all committed to doing the right thing, but felt we couldn’t because of lacking resources and prioritization.

After: Security as Aspirational Ideal

And then the memo came out. I myself wasn’t involved in it; I was too deep in the trenches. So, Gates' memo came as a bit of a surprise to me and to some of my colleagues. It’s not an understatement that the memo felt, to me, like the arrival of Gandalf and Eomer at Helm’s Deep in the film "The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers" at a moment of great despair; at last we were getting some relief and might survive.

There was understandable skepticism outside Microsoft that the memo was just a publicity stunt to blunt the criticism the company was getting then. And yes, the memo did serve that purpose. But it was real. Memos from Gates were viewed as rare pronouncements from on high, and that was the case with this memo. In a single movement, Gates enshrined security, privacy and reliability as central, aspirational ideals. Like all ideals, there have been better and worse times in realizing them, but their central importance was never open to question. That memo eliminated the resistance that made our work so hard and gave us the power to do the right thing for customers.

Of course, the memo didn’t fix things overnight. The next two years would see the Slammer and Blaster worms, even more damaging than the worms of 2001. At the same time, a huge buildup and mobilization was happening internally to meet those threats. It took a number of years, but that memo led to the MSRC of today: a group that provides the most comprehensive and efficient response to vulnerabilities and attacks in the industry (and works to share that capability and coordinate with others).

Equally important, it led to the Security Development Lifecycle (SDL), which has made great strides in making Microsoft’s newer products some of the most secure in the industry. The mark of that memo’s success around security response: it’s actually become rather boring from the outside (though I assure you it’s still not boring on the inside).

The Future: Not One Memo, but Many

But as we look at the successes the memo has yielded after 10 years, I think it’s more important to look forward. Specifically, during the next 10 years, other companies in the industry should emulate the aspirational ideals around security and privacy put forth in the Trustworthy Computing memo, and make them centerpieces in their respective cultures.

When the memo came out, the MSRC and SWI were responsible for protecting approximately 90 percent of the people on the global Internet. So, the improvements this memo put in motion helped improve the security and privacy of 90 percent of the world’s computers. The reality today is that no one company can do that much good for so many. In the era of mobile and cloud computing, the market is more fragmented. Overall, that’s good for everyone. However, because only one major player in this space has enshrined these ideals around security and privacy, it means real security and privacy for people is at risk in a way we haven’t seen since before 2002.

In the rush-to-market frenzy today, we’re seeing the same bad decisions that Microsoft and others made in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Those who want to do the right thing for customers at other companies lack the leverage that their counterparts at Microsoft have in the form of that memo. While much of the great talent that Microsoft assembled over the years has moved on to these other companies, spreading the knowledge gained as they go, their jobs are harder because they have to fight the same battles that Gates’ memo put paid to in 2002. At Microsoft, there is no question that security is a part of the development process; there is no question that vulnerabilities will be addressed. Other companies can’t necessarily say the same thing.

During my time at Microsoft, the Trustworthy Computing memo empowered us as we stood for the security and privacy of customers and stood toe-to-toe with those in the company whose primary concern was revenue and growth. It gave equal weight to both sides. In a way, it represents a statement of conscience for the company and we used it as such, with success. Now, the best thing for it, like all ideals, is to break free and work for the good of more than just the person or company who thought of it.

Hopefully, 10 years from now, we will be talking not just about Bill Gates’ Trustworthy Computing memo, but also Jeff Bezos', Larry Page's, Mark Zuckerberg's, and others. At the end of the day, where security and privacy are concerned, many of us who were in the trenches at Microsoft weren't just protecting the company's customers. We were protecting people and we wanted, and still want, to do what's right for everyone.

Photo and Chart Credits: Microsoft

Christopher Budd is a 10-year veteran of Microsoft, where he oversaw and managed communications around online security and privacy incidents. He left the company in December 2010. Today he is an independent consultant using his experience to help clients in the areas of crisis communications, online security and privacy incidents and social media.

Christopher Budd is a 10-year veteran of Microsoft, where he oversaw and managed communications around online security and privacy incidents. He left the company in December 2010. Today he is an independent consultant using his experience to help clients in the areas of crisis communications, online security and privacy incidents and social media.

Data on up to 24 million customers of online shoe retailer Zappos was compromised according to an email sent by its CEO Tony Hsieh on Sunday. While Hsieh says that full credit card information is safe, hackers may have the last four digits of the cards.

Data on up to 24 million customers of online shoe retailer Zappos was compromised according to an email sent by its CEO Tony Hsieh on Sunday. While Hsieh says that full credit card information is safe, hackers may have the last four digits of the cards.

I joined the

I joined the

If you want to view the created, accessed or last modified dates of a file from Explorer then that’s easy enough (right-click, select Properties).

If you want to view the created, accessed or last modified dates of a file from Explorer then that’s easy enough (right-click, select Properties).