By Joe Wilcox, Betanews

Apple apologists need to get a grip regarding a reported US Federal Trade Commission investigation. It's not the least surprising, and Apple has a discernable monopoly around which business practices the FTC -- or even the US Justice Department -- would want to monitor.

The apologist line is this: Apple doesn't have a monopoly for cell phones and has the right to decide what developers can do or which ones have access to the iOS platform. In my May primer, "10 things you should know about Apple and antitrust," I explain how the company has two monopolies, and one of them is large enough to trigger an investigation (and there is official complaint from Adobe). If you haven't read that post, stop reading this one and go to that one. Then come back here, of course.

Apple's monopolies are digital music players and mobile applications, and the two share something in common: iTunes, which is the distribution, payment and synchronization hub for both. Apple's App Store is unquestionably the largest of its kind anywhere in the world: More than 225,000 applications and more than 5 billion downloads. The App Store supports three Apple devices: iPad, iPhone and iPod touch -- and the company has sold close to 100 million of these devices.

Absolutely, Apple has a monopoly, ah, plural. Apple is doing much the same with its platform as Microsoft did in the 1990s and 2000s: Build a largely integrated product stack, only Apple's is tighter. Microsoft integrated software and services. Apple integrates hardware, software and services. Similarly, both platforms cater to developers but not necessarily evenly. If Apple has a monopoly position affecting software developers, as Microsoft did with Windows, somebody will look at the competitive practices.

One issue: What US lawyers referred to as the "applications barrier to entry" during Microsoft's trial. The concept is simple: The monopoly prevents other applications entering a market, causing consumer harm. Something else: There is another way that Apple and Microsoft are similar. Microsoft's integrated technologies either favor Windows or are exclusive to it. Apple's position is similar and arguably more so, since it's a tight integration of hardware, software and services. The stack's integration and Apple's control over it can shut out competitors -- the aforementioned applications barrier to entry. Whether or not the FTC finds Apple engaged in anticompetitive behavior is another matter. It's too soon to definitively say.

Some readers will ask: "Well, why shouldn't Apple have say over its platform technologies?" I asked the same question about Microsoft during its US antitrust case, as did the company's lawyers and other supporters. I'll use what some people will call a terrible analogy. The family. In a family, parents' expectations about children's behavior change as they mature, particularly when there are other kids. Parents expect older children to share some responsibility over their siblings or, at least, not to take advantage of physical size and maturity. Similarly, US antitrust law applies stricter rules to larger companies than to smaller sizes. There is greater expectation of fair play and even patronage -- that larger companies take leadership roles fostering competition. It's a lovely concept, but there's nothing fair about business, which is more survival of the fittest. They compete or die.

Apple's argument for how it runs App Store reminds of Microsoft's defenses during its antitrust trial. Number one: The customer. Microsoft lawyers and executives asserted that the company acted to serve customers not thwart competitors -- although it is easily argued that much of the behavior served dual purposes. Apple's position is similar. It shuts out platform competitors like Adobe in part because they use private APIs. During last week's Worldwide Developer Conference, CEO Steve Jobs said that private third-party APIs present problems when Apple updates iOS. "If they change the app will break." He emphasized: "We'll have unhappy customers. If they upgrade their OS and half the apps break, they're not going to be happy campers."

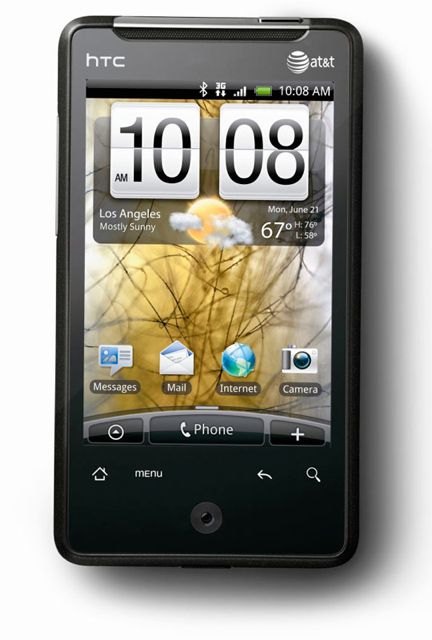

From Apple's perspective, that's a reasonable argument -- as was Microsoft's stance about the customer when defending tight control over the Windows home screen and desktop and approach to disclosing information about APIs. Apple should want to preserve the customer experience, particularly as competition heats up. One day before iPhone 4 preorders start, AT&T launched a new Android handset. Even on iPhone's home US network, Google's mobile OS competes against iPhone and now more formidably. Unlike AT&T's other Android handset, the Motorola Backflip, the HTC Aria runs Android 2.1.

Apple's problem is this: Adobe is welcome on Android, something Google can't seem to promote enough. Adobe Air and Flash are prohibited from iOS. Apple's private API defense is weaker if Google and other mobile OS developers embrace Adobe. App Store is considerably larger than Android Marketplace, which has more than 50,000 applications. These are all reasons for FTC to take actions opening up iOS.

However, there's another perspective. The Android Marketplace grew from about 10,000 apps six months ago to the more than 50,000 today. Google says it is activating 100,000 Android phones per day. Android is coming to TVs later this year and to tablets. Google's OS is growing up fast. The question the FTC should ask: Would forcing Apple to let in private API developers like Adobe level the competing playing field or give Google a free pass? I ask you to answer the question in comments.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2010

Microsoft

Microsoft -

iPhone -

App Store -

Apple -

Steve Jobs

AT&T was the last of the "big four" U.S. mobile operators to start selling phones based on Google's Android operating system, and has only had a single Android phone available

AT&T was the last of the "big four" U.S. mobile operators to start selling phones based on Google's Android operating system, and has only had a single Android phone available  Even before the doors of the Electronic Entertainment Expo got to open, the name of Microsoft's Xbox 360 motion controller has been revealed. Formerly known by its project name, Natal, Microsoft's camera-based motion controller will be known as Kinect when it comes to market later this year.

Even before the doors of the Electronic Entertainment Expo got to open, the name of Microsoft's Xbox 360 motion controller has been revealed. Formerly known by its project name, Natal, Microsoft's camera-based motion controller will be known as Kinect when it comes to market later this year.