By Scott M. Fulton, III, Betanews

The nice thing about the Internet, or so I've been told, is that it has all this information. Perhaps you've noticed this lately, but the big problem has been that there's no one way to get at this information with any kind of consistency.

The nice thing about the Internet, or so I've been told, is that it has all this information. Perhaps you've noticed this lately, but the big problem has been that there's no one way to get at this information with any kind of consistency.

Supposedly Google is the "portal" for most of the world's information, which may be why so many people find Betanews by typing "Betanews" in Google. In one respect, you might expect Google to have an interest in creating that consistent methodology for getting at information. On the other hand, given that so many folks depend on Google Search just as it is now, you could see how Google might very easily come to the conclusion that there's no new benefits to be gained through improving its software, just to keep the user base it already has.

My friend and colleague Carmi Levy touched on that point this morning in Wide Angle Zoom, where he turned a reluctant thumb down on the Google Buzz social network experiment. You can call it "beta" or, as Google strangely decided this time around, not call it beta, but after using it for a while, it's difficult not to come away with the opinion that this is indeed an experiment...and you're the subject.

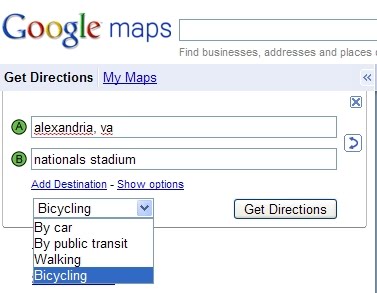

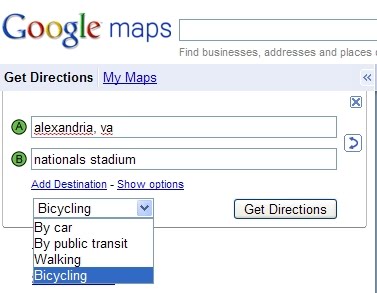

But as Carmi also noted, different Google services are so inconsistent with one another that they may as well have been developed on different planets -- which suggests that Google may have been copying the Microsoft development model after all. Perhaps the best case-in-point example comes from Google Maps. Yesterday, to the delight of many, it added bicycle routes to its plotting options.

If you're a biker, you know that there are peculiar distinctions between the routes you plan as a pedestrian, and those you use on a bicycle. In cities whose planning commissions have added lanes to boulevards by destroying sidewalks, you know that unless you enjoy motocross and frequent encounters with beat cops, you can't plant bicycle tires on the same places you can plant your feet. I grew up decades ago in Oklahoma, at a time where for most areas of the state, "downtown" was denoted by the presence of the stoplight. Before I could drive a car, I biked four miles back and forth from my first high school, and (sometimes) the ten miles back and forth from my second, at a time when that was considered a normal way for a kid to get around town. Even then, I distinctly remember there were spans of a few hundred feet or so every so often where, if the paved road ended and the granite rock paths began, I'd pick up my bike and tread on foot between people's houses. It helped to get acquainted with them first (see: "beat cops").

The brilliance of the Google Maps experiment is that it accumulates the data that Google has gathered, not just through map scanning and satellite imagery and those strange cars you see cruising every little granite path, but through its advertising service as well. As a result, from day one, the bicycle route part of its service is capable of guiding cyclists using the tools that matter to cyclists: the landmarks they see along the way -- the gas station, the church with the tall steeple, the Italian restaurant. No service established exclusively for the purpose of mapping the world, for motorists or cyclists, would have ever assimilated information at this level of granularity; only through co-opting the advertising and location database with the mapping database could this ever be feasible from a business standpoint.

When I tested Google Maps last year as a pedestrian/public transit dependent in Los Angeles, I discovered it was using a form of "reverse tunnel logic" to compile its suggested routes. Quite literally, it would have me traveling by foot one mile south to catch a bus that would take me 1.1 miles north; and it also would have had me scaling viaducts where there were drainage ditches below and barbed wire above. I pointed out to Google at the time that Maps appeared to fail to consider time and effort consumed as factors in assimilating its routes. The response I got at the time from Google was, thank you for your input but, well, you can't know everything about everything.

As I've learned from experience, yes, you can. Living in Indianapolis, for example, I know there is a kind of "superhighway" exclusively for non-motorists, formed from the brilliant idea of paving over a disused railroad track. Named for the railroad that used to own it, it's called the Monon Trail -- a 16.7-mile stretch of track that's well kept, fairly well patrolled, and is the most foot-friendly stretch of asphalt I've ever traveled.

Since it bisects most of the city north-to-south, there are a multitude of ways someone could get to the Monon Trail. Indianapolis is notable for having plenty of bike trails in certain areas of the city, and no way in hell a bike could get through in others. For my initial test of Google Maps for cyclists, I wanted to see whether it would make the same decisions I would, having lived here now for 18 years.

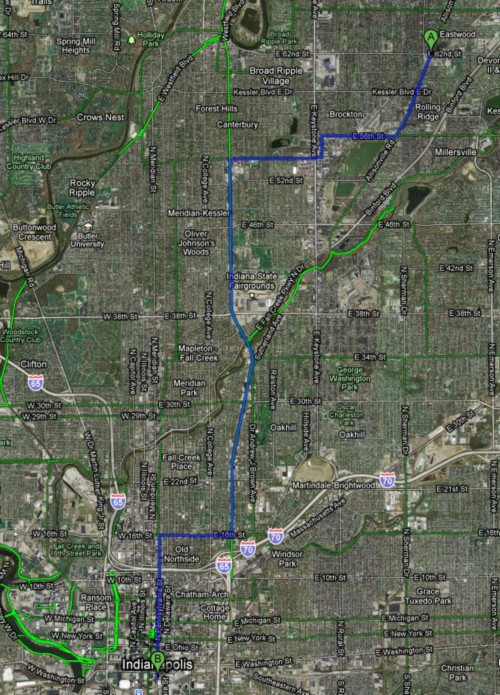

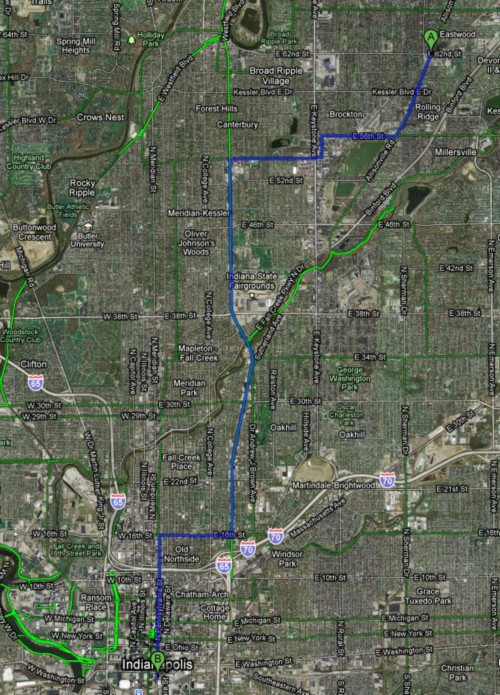

With pedestrian maps, Google's suggested route is plotted in blue, with the relatively foot-friendly paths outlined in solid green, or dotted green for "better than most." If I wanted to walk from my house all the way to, say, Conseco Fieldhouse downtown where the Pacers play, Google Maps would try to plot the most direct foot route it could. Even though I know for a fact that walking the Monon Trail is much, much faster than down the side of a boulevard, the fact that the Trail is a half-mile out of my way means that Google's walking map won't suggest it.

It is a very different story for cyclists, and here it's clear that someone at Google listened to my advice. It takes a little more effort to pedal west a half-mile to get to the Trail, but once you're there, the effort pays off with a four-and-a-half mile stretch of paved roads, overpasses, and relatively safe crosswalks ("zebra crossings"). Tunnel logic evidently was not used to compile this route, but rather an assessment of the time and even luxury benefits to be gained from going out of one's way -- the type of assessments Google Maps did not make last year in L.A.

Here's what I mean: This screenshot shows the suggested route from one of my favorite neighborhood pizza joints to Conseco downtown. Now, Google knows that Allisonville Road recently added a bike lane (not a good one, it's in dotted green), that it leads to a nicely protected sidewalk down Fall Creek Parkway, and that would be the most direct route downtown. Indeed, if I were a pedestrian, that's the route it would suggest. But as a cyclist, I know that's not the route I want -- crossing onto Fall Creek over Binford Blvd. means running across ten lanes of traffic without a crosswalk, where motorists are speeding through on a shortcut to I-69.

Here's what I mean: This screenshot shows the suggested route from one of my favorite neighborhood pizza joints to Conseco downtown. Now, Google knows that Allisonville Road recently added a bike lane (not a good one, it's in dotted green), that it leads to a nicely protected sidewalk down Fall Creek Parkway, and that would be the most direct route downtown. Indeed, if I were a pedestrian, that's the route it would suggest. But as a cyclist, I know that's not the route I want -- crossing onto Fall Creek over Binford Blvd. means running across ten lanes of traffic without a crosswalk, where motorists are speeding through on a shortcut to I-69.

So Google Maps takes my bicycle (a vintage Takara racer, if you're interested) a mile out of my way, through a residential area, just to get me to the Monon Trail. And that's exactly right -- there's no question it's a lovelier, easier, and in good weather, faster route.

Next: Seeing where you're going, and where you shouldn't go...

Seeing where you're going, and where you shouldn't go

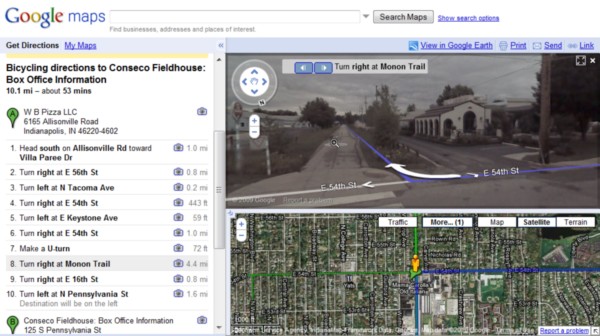

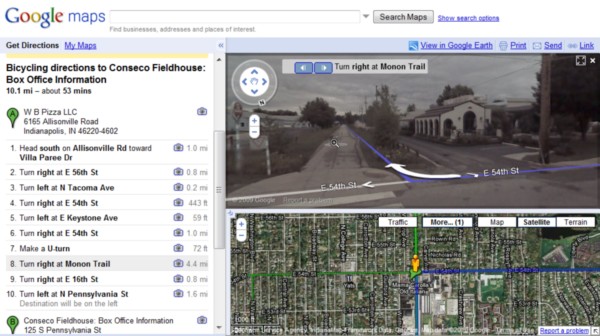

Perhaps the most wonderful feature of this service, which pedestrians already discovered, is the opportunity to blend Street View with maps to let you walk the route ahead of time. This way you see in advance all the landmarks you'll encounter along the way -- the waypoints that let you remember in your head what to look for and where to turn. Here is where I encountered a little bug in the program, and you can actually see it if you look closely here.

Street View should show you a blue line, coordinating with the blue line in the overhead map, to let you follow the suggested route. The overhead map, shown below, appears correct -- travel west on 54th St., and turn left at the Trail. The landmark at that turn is one of my favorite Italian restaurants in all the world, Mama Carolla's. In the photograph, notice the trail runs right alongside it.

Notice also that the map's blue line has you making a left turn at Mama's onto the Trail (correct), but that Street View has you making a right turn. What happened here? A check of the turn-by-turn directions reveals that, for some strange reason, Maps wants you to travel down 54th St. for 72 extra feet, then make a U-turn, head back the other direction, and make a right turn. It's probably a little database problem, where the point of contact with the Monon Trail meets up with the street is off by a few feet. Nevertheless, if you printed off these directions so you could follow them from your bike, you'd be confused at this point.

Here's also where you discover a problem that Google can't solve, at least not right away: You can't take a Street View walk down pedestrian trails. There's an obvious reason for this: Towns don't want Google going down walking trails snapping shots of people anonymously.

The next best thing is to try to reposition yourself (the little orange man on the overhead map, who I've noticed isn't on a bike) on actual street intersections along the way. Here's where the software starts to fail: I should be able to just click on the blue path at an intersection where there's a photo. Instead, I have to drag the little man up in the air (he actually "flies" while this is happening, like a repositioned character in Peter Molyneux's game "The Movies") and deposit him in the vicinity of the blue line. Where it ends up dropping him, despite what the pointer says, could be up to three blocks out of the way.

The problem here appears to be with the front end of the program, not with the fundamental design. If you'll recall earlier my statement that you can know everything, the way you do so is by listening and learning. Google Maps is, to its great credit, capable of doing this: In cases where I know full well a certain route is safer or better than another, I can drag the blue line where I believe it should go. Not only is that an easy way for me to plan my own route, but for Google, it's a source of new information: If Google is smart about this (and there's no reason for me to believe it isn't), it will learn from my changes and those of others, and may suggest safer routes for other Maps users in the future.

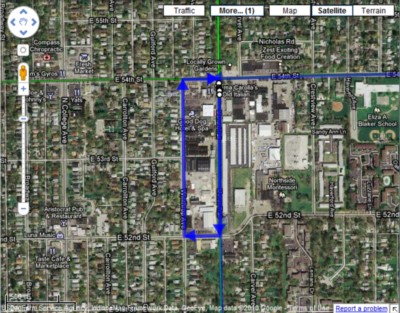

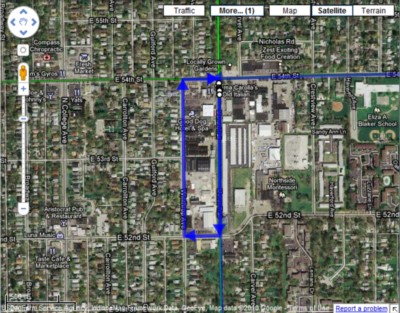

But it can only do this if it gets its front end right first. The slightly incorrect portion of its suggested route for my trip downtown was a 72-foot diversion that actually does show up when you zoom in the map. But partly because the granularity of the line-dragging routine does not appear to be as fine as the map's own zoom capability, and partly because the U-turn is a three-step process which Google Maps presumes must lead from point to point to point in every circumstance, my attempt to simply shave off the U-turn in the directions was mistaken as a way for me to take a lap around the strip mall parking lot, shown here.

But it can only do this if it gets its front end right first. The slightly incorrect portion of its suggested route for my trip downtown was a 72-foot diversion that actually does show up when you zoom in the map. But partly because the granularity of the line-dragging routine does not appear to be as fine as the map's own zoom capability, and partly because the U-turn is a three-step process which Google Maps presumes must lead from point to point to point in every circumstance, my attempt to simply shave off the U-turn in the directions was mistaken as a way for me to take a lap around the strip mall parking lot, shown here.

Because Google is leveraging its massive platform in multiple areas to provide an exclusive service that wouldn't have been feasible on its own, little adjustments can have big consequences. Someplace within the Google database right now, there's probably the recording that some Indy cyclist weirdo suggested that instead of a simple 72-foot loop around the middle of 54th St., one should take a big two-block oval around the strip mall. As long as that little route-adjustment bug is in there, the validity of information Google is gleaning from changes that sensible people are making to suggestions everywhere, may end up not being very sensible. And as a result, over time, someone will probably be advised to walk one mile north in order to get on the route that leads her 1.1 miles south.

Despite that little discovery, I can easily see where Google Maps will become an invaluable tool for bicyclists who want to explore not only their home town, but areas of the world they've never been. I can imagine a depression in car rentals across the country. I'm also imagining folks with their Android GPS-enabled phones in their pockets maybe someday getting spoken directions. "Turn left onto Monon Trail...No, silly, your other left."

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2010

The nice thing about the Internet, or so I've been told, is that it has all this information. Perhaps you've noticed this lately, but the big problem has been that there's no one way to get at this information with any kind of consistency.

The nice thing about the Internet, or so I've been told, is that it has all this information. Perhaps you've noticed this lately, but the big problem has been that there's no one way to get at this information with any kind of consistency. Here's what I mean: This screenshot shows the suggested route from one of my favorite neighborhood pizza joints to Conseco downtown. Now, Google knows that Allisonville Road recently added a bike lane (not a good one, it's in dotted green), that it leads to a nicely protected sidewalk down Fall Creek Parkway, and that would be the most direct route downtown. Indeed, if I were a pedestrian, that's the route it would suggest. But as a cyclist, I know that's not the route I want -- crossing onto Fall Creek over Binford Blvd. means running across ten lanes of traffic without a crosswalk, where motorists are speeding through on a shortcut to I-69.

Here's what I mean: This screenshot shows the suggested route from one of my favorite neighborhood pizza joints to Conseco downtown. Now, Google knows that Allisonville Road recently added a bike lane (not a good one, it's in dotted green), that it leads to a nicely protected sidewalk down Fall Creek Parkway, and that would be the most direct route downtown. Indeed, if I were a pedestrian, that's the route it would suggest. But as a cyclist, I know that's not the route I want -- crossing onto Fall Creek over Binford Blvd. means running across ten lanes of traffic without a crosswalk, where motorists are speeding through on a shortcut to I-69.

But it can only do this if it gets its front end right first. The slightly incorrect portion of its suggested route for my trip downtown was a 72-foot diversion that actually does show up when you zoom in the map. But partly because the granularity of the line-dragging routine does not appear to be as fine as the map's own zoom capability, and partly because the U-turn is a three-step process which Google Maps presumes must lead from point to point to point in every circumstance, my attempt to simply shave off the U-turn in the directions was mistaken as a way for me to take a lap around the strip mall parking lot, shown here.

But it can only do this if it gets its front end right first. The slightly incorrect portion of its suggested route for my trip downtown was a 72-foot diversion that actually does show up when you zoom in the map. But partly because the granularity of the line-dragging routine does not appear to be as fine as the map's own zoom capability, and partly because the U-turn is a three-step process which Google Maps presumes must lead from point to point to point in every circumstance, my attempt to simply shave off the U-turn in the directions was mistaken as a way for me to take a lap around the strip mall parking lot, shown here. With Mini 5, Opera Software has managed to make a cross-platform browser that provides an almost uniform experience across all the operating systems it runs on. Today's release on Android feels almost identical to the version I tested last week.

With Mini 5, Opera Software has managed to make a cross-platform browser that provides an almost uniform experience across all the operating systems it runs on. Today's release on Android feels almost identical to the version I tested last week. There are so many reasons to rant on Google for foisting yet another social media failure on us, but for now, I've narrowed it down to these four:

There are so many reasons to rant on Google for foisting yet another social media failure on us, but for now, I've narrowed it down to these four: