We have a problem understanding devices that live outside of the commonly accepted "three screens" model. It's the model that has been pushed by big companies such as AT&T, Verizon, Nielsen, and Microsoft which says that our main windows into content consumption are the TV, PC, and mobile device.

If a device's functionality falls somewhere between one of these three screens, it gets marginalized and written off as something that doesn't address a specific need.

That's actually one of the first criticisms from US consumers reacting to the Apple iPad.

It is a device that we "don't need," and is simply another way to sell iTunes content, some said. People could not look at the iPad and instantly state its principal, core functionality like they could for the rest of Apple's product line. They could say, for example, that the iPod is a music player, the iPhone is a mobile phone, and AppleTV is a connected set-top box.

It is a device that we "don't need," and is simply another way to sell iTunes content, some said. People could not look at the iPad and instantly state its principal, core functionality like they could for the rest of Apple's product line. They could say, for example, that the iPod is a music player, the iPhone is a mobile phone, and AppleTV is a connected set-top box.

And while all of those devices offer a lot more than those basic descriptions tell you, at their heart, they have a single purpose, an identity. The iPad didn't immediately click with that identity.

Even Apple CEO Steve Jobs marginalized the iPad as "something between a laptop and a smartphone," which focuses on functionality already delivered by the other devices like browsing the Web and consuming streaming media. "It's going to have to be better at these kind of tasks than a laptop or a smartphone, otherwise, it has no reason for being," Jobs said in January.

That's a pretty damning set of guidelines. But it may be better to wedge a new device in between two of our three screens than to give it a vague, almost purposeless description like Intel has done with the Mobile Internet Device profile and Microsoft has done with the Origami/Ultra Mobile PC (UMPC) profile.

When these device classes premiered in 2006, Microsoft didn't even tell us what made something an Origami device, much less how they were supposed to fit into our lives. The Origami campaign slogan was literally "What is Origami?" and it actually tried to make its case on the premise that there was no case to make -- you fill in the blank.

![An early prototype Origami UMPC device running Windows XP, believed to have been manufactured by Samsung. [Photo credit: Wolfgang Gruener for TG Daily, 2006]](http://images.betanews.com/media/4573.jpg)

An early prototype Origami UMPC device running Windows XP, believed to have been manufactured by Samsung. [Photo credit: Wolfgang Gruener for TG Daily, 2006]

But Microsoft's description of Origami PCs is familiar: a device with "a powerful processor, a big, bright display, easy-to-use input options, and support for the latest connectivity standards...The UMPC offers a display of 4-7 inches and touch capabilities, all in a package that weighs less than 2 pounds." All this was expected in a package that cost between $599-$799.

But Microsoft's description of Origami PCs is familiar: a device with "a powerful processor, a big, bright display, easy-to-use input options, and support for the latest connectivity standards...The UMPC offers a display of 4-7 inches and touch capabilities, all in a package that weighs less than 2 pounds." All this was expected in a package that cost between $599-$799.

Why, that sounds just like the iPad, doesn't it?

So what, exactly, made Origami the crashing failure that it was, dubbed by one publication, "The biggest flop since Windows ME?"

The problem was not simply that Origami, or UMPC, or whatever you want to call it, didn't have a clear purpose (or even a clear name). It was too heavy, too resource-constrained to run a desktop OS, its battery life was too short, and its input method was weak.

Things haven't fared any better for the device category dubbed MID by Intel. Instead of being declared a total flop, manufacturers have gradually converged that platform with mobile phones, while Intel -- which at one time actively avoided the term 'netbook' -- has now actively abandoned it altogether. Intel is now not only free, but content, to embrace MID's successor, complete with its own device architecture (Atom) and operating system (MeeGo, formerly Moblin).

Back in 2008, comScore said that smartphones were actually cutting into the low-cost computing segment populated by netbooks and MIDs.

"Smartphones, and the iPhone in particular, are appealing to a new demographic and satisfying demand for a single device for communication and entertainment, even as consumers weather the economy by cutting back on gadgets," comScore said.

The very things that were supposed to make MIDs stand out -- their lower cost and easy Web browsing experience -- were being squeezed out by smartphones that were cheaper, more versatile, and just as enjoyable to browse with. Why would a consumer pay the the same price for a MID with only Wi-Fi that they would for an unlocked top-of-the-line smartphone?

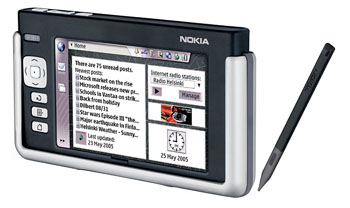

Major mobile phone maker Nokia, which has been dabbling in MIDs for more than five years, has nearly drawn its efforts in MIDs to a close. In 2005, the company launched the Nokia 770 Internet Tablet, with a 4.1" touchscreen and and the Linux-based maemo MID platform (which was merged into Moblin earlier this month). Looking at it now, the 770 (pictured right) isn't really not that far off from a smartphone, except that it's a bit chunky around the middle.

Major mobile phone maker Nokia, which has been dabbling in MIDs for more than five years, has nearly drawn its efforts in MIDs to a close. In 2005, the company launched the Nokia 770 Internet Tablet, with a 4.1" touchscreen and and the Linux-based maemo MID platform (which was merged into Moblin earlier this month). Looking at it now, the 770 (pictured right) isn't really not that far off from a smartphone, except that it's a bit chunky around the middle.

Four years later, Nokia slimmed down its MID profile, shrunk the touchscreen to just under 4 inches, and equipped it with cellular radios. The N900, which will be the last device to run on the maemo MID platform, is for all intents and purposes a smartphone.

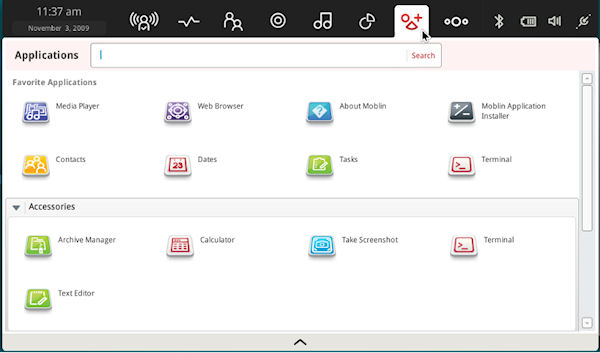

When maemo is finally merged with (read: "consumed by") Moblin (pictured above) in the new MeeGo platform, the result will be an open, Linux-based operating system designed for a number of device classes, like smartphones, netbooks, notebooks, and embedded environments. Nokia's MID-centric operating system is marked for death.

And yet, just when it looks like the MID is dying, there are some who argue that it's only just now reaching the point where it could break through in the Americas.

Inbrics has made $170 million selling mobile devices in its home country of South Korea, and it has made impressive appearances both at CES and GSMA Mobile World Congress this year, showing off a device that looks exactly like an Android superphone, but without a cellular voice module. Just like Nokia's N900, the Inbrics M1 Identity is a MID in function but a smartphone in form.

"We expect the demand for MIDs in North America to rise at the end of 2010 and into 2011," Inbrics' chief marketing officer Bobby Cha told Betanews. "All of the major wireless carriers have a plan that includes a MID separate from their phones."

"We expect the demand for MIDs in North America to rise at the end of 2010 and into 2011," Inbrics' chief marketing officer Bobby Cha told Betanews. "All of the major wireless carriers have a plan that includes a MID separate from their phones."

The M1 Identity is an iPod-thin device that looks pretty much like a high-end mobile phone, with a 3.7" capacitive AMOLED touchscreen, a full QWERTY keyboard, 800MHz applications processor, 16GB of memory, running Android 1.5 with its own custom UI that includes an in-depth home media controller poetically called the "3 Screens Manager."

Cha says the key to MID adoption will come as Americans change the way they interact with their phones. "In Asia, the typical user doesn't hold their phone up to their ear. They hold it in front of their face...We have the innate ability to change the way the consumer interacts with their content."

Laptop Magazine ran an article last week called "Do Americans Really Care About MIDs?" which examined a crop of Mobile Internet Devices that are expected this year.

I was honestly taken aback. I thought the answer was pretty clear by now. The only MIDs Americans care about are smartphones.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2010