By Angela Gunn, Betanews

So I'm launching a security column on the anniversary of the Hindenberg disaster. Seems right.

So I'm launching a security column on the anniversary of the Hindenberg disaster. Seems right.

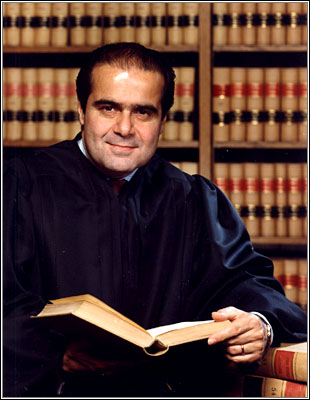

Speaking of things that blow up and embarrass political figures: Did you enjoy the excitement recently when a Fordham law-school class tested Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia's assertion that consumers don't really need more personal-privacy protections? If you missed it, Joel Reidenberg's class went online to see how much free, publicly available information it could turn up on the justice, who has stated previously that he doesn't see a need for greater legal protections for privacy.

The class did well, compiling a 15-page dossier that includes Scalia's home phone number and address, the value of that home, his favorite food and movies, his wife's e-mail address, and photos of his grandchildren. In response, Scalia told the Above The Law blog that "It is not a rare phenomenon that what is legal may also be quite irresponsible. That appears in the First Amendment context all the time. What can be said often should not be said. Prof. Reidenberg's exercise is an example of perfectly legal, abominably poor judgment. Since he was not teaching a course in judgment, I presume he felt no responsibility to display any."

Feisty little thing, isn't he? Only problem is, he obviously doesn't get out much -- not out to the real world, anyway, where as security folk know it's hard enough to get civilians to refrain from doing stuff that's actively forbidden, let alone the stuff that merely shows abominably poor judgment.

The problem with calling the dossier assignment an exercise in poor judgment is exactly the same problem security folk have when trying to get users to do their bidding, or that people like me have when I'm trying to explain to Mom why she shouldn't click on every single link she gets in AOL Mail: One person's poor judgment is another person's differing set of priorities.

By Professor Reidenberg's lights, this has been a damn fine course of action: On the debit side, one panty-bunched Supreme; on the credit side, an effective classroom project and a great jump-start to the PII debate. The problem now of course is finding a debate hall big enough to accommodate everyone who's got an opinion on the matter.

By Professor Reidenberg's lights, this has been a damn fine course of action: On the debit side, one panty-bunched Supreme; on the credit side, an effective classroom project and a great jump-start to the PII debate. The problem now of course is finding a debate hall big enough to accommodate everyone who's got an opinion on the matter.

Ask the Virginia Prescription Monitoring Program hacker if he feels okay with his data-collection priorities; go back in time a couple of weeks and ask the security crew on that project how they feel about their own risk assessment; ask the person responsible for that department's budget how s/he feels about their allotment. And so on. (You could maybe also ask one of the eight million patients whose data was allegedly snatched, but who ever does? Justice Scalia may feel sorely put-upon, but in fact he's lucky anyone bothered to get his opinion at all.)

This is a security column, not (most weeks) a tech-policy-and-law column; we'll be getting into HIPAA and FISMA and other alphabet soup now and then, but let's assume for now that we'll do so to get at the tech angle(s) on the matter. In that case, what's the lesson from the lesson? Smart security folk already know that information that goes online stays online -- as does information that goes on paper, into a credit-card database, through your cable-TV remote control... if it's outside your head, it's probably beyond your control. The law can't fix that; it can only declare that we the people, collectively, place a priority on not gathering it for purposes unknown, or curating it in ways that make its originators see red.

Copyright Betanews, Inc. 2009