If Google's vice president is to be believed, we are in danger of losing an entire generation of information to the digital realm. Look to the history books, and you do just that -- look in a real, physical book. Pictorial histories can be found in photo albums. The works of Oscar Wilde, Samuel Pepys, and Charles Dickens are stored in real, tangible formats.

But now just about everything is stored digitally. Photos are rarely, if ever printed; millions of words are published online each day on blogs, online newspapers, and message boards. These are all important social, political, literary, and historical records. There's no guarantee that the sites, apps and technology needed to access all of these records will still be available in 50 years or more. Could our history be lost to the cloud?

Every day we post reams of information to Facebook and Twitter, and it's usually stuff we have no 'backup' of. Upload a photo and there's a high chance that you have a copy stored on your phone, camera or computer, but the same cannot be said of every bon mot penned. It's easy to deride the contents of social networks as material that we should just forget about, but historians in several hundred years' time may well find it difficult to piece together what it meant to be alive in the late twentieth/early twenty-first century.

Google and other companies have quite a propensity for shutting down services willy nilly -- Helpouts is just the latest in a long line of victims. Speaking at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Google's VP, Vint Cerf said:

When you think about the quantity of documentation from our daily lives that is captured in digital form, like our interactions by email, people’s tweets, and all of the world wide web, it's clear that we stand to lose an awful lot of our history [...]We don’t want our digital lives to fade away. If we want to preserve them, we need to make sure that the digital objects we create today can still be rendered far into the future.

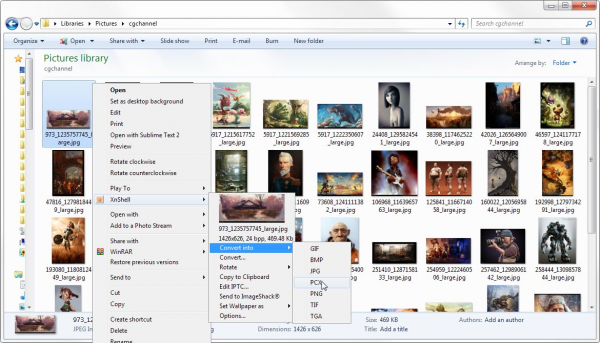

We can't be sure that everything we say on Facebook will be accessible next year, let alone in a couple of decades. We have no guarantee that images currently stored as JPEGs will be as easy to open in 2115 as they are in 2015 -- the software horizon is completely unknown. In the relatively short time in which digital documents have become the norm we have already seen a number of once-popular file formats fall by the wayside. Conversion tools are available in many cases, but not in all.

The likes of Word are likely to stick around for longer than any other formats, but there is a danger that we would reach a time when opening certain types of documents requires specialist intervention. Old computer systems and games consoles are consigned to museums. Could the software you are working with at the moment become the Pong of tomorrow?

Storing anything digitally leaves it open to a serious problem -- security. Chuck your data to the cloud, and you're placing a lot of trust in the companies involved to keep your files safe. But if something goes wrong -- from a company closing down, through a hardware failure that wipes out files, to a hack attack -- there is no way of knowing that your cloud-stored information will continue to be available to you.

It's a problem exacerbated by the huge range of mobile apps that are now out there, each storing files in their own unique, often incompatible formats. When it comes to apps for phones and tablets, storing data in the cloud is very much the norm -- it's just the way things are. Too many apps fail to provide a way (or at least an easy or free way) to convert data into another format that would allow it to be used with another piece of software. Patents and IP laws often stand in the way of enterprising programmers from creating their own conversion tools.

This is far from the only concern. The sheer volume of data we all create on a daily basis is staggering

Talking to TechRadar, Mark Whitby, Senior Vice President of Branded Products Group at Seagate Technology, said that our data storage needs are spiralling out of control:

The total amount of digital data generated in 2013 was about 3.5 zettabytes (that's 35 with 20 zeros following). By 2020, we'll be producing, even at a conservative estimate, 44 zettabytes of data annually.

Our data is spiralling out of control. Whether it is stored on hard drives or in the cloud (which ultimately means that it is stored on a hard drive somewhere) we generate countless libraries worth of information every day with no guarantee that it will be accessible in the next century. How much data do you have stored on old 5.25 inch disks, 3.5 inch floppies, or even CD-Rs that are unreadable? It might not just be that you don’t have the drives necessary to read these various types of storage, but that the media is prone to deterioration over time. And this is still where we're relatively in control of it. We have no idea how accessible our cloud data will be further down the line. No idea whatsoever.

CDs we created a few years ago have already become unreadable with age. DVDs and Blu-ray discs will suffer the same fate, and it would be naïve to believe that the hard drives and memory built into so many devices are not prone to the same problem.

The lure of the paperless office means that less and less information is stored on slices of tree, but this is the format that has proved to be one of the most enduring throughout history. Perhaps it's time to dig out the printer, invent in a bunch of ink and start running off hard copies of everything we couldn’t bear to lose.

Right... who's going to print out Wikipedia?

Photo credit: Bruce Rolff / Shutterstock